I showed up at Air Force pilot training with twenty-five hours of flight time. That was a bit below average, but not much. The high timer in our class had 2,000 hours, but he barely graduated.

— James Albright

Updated:

2012-09-26

It seemed civilian time was not a predictor of success. Still, those of us starting with almost no time had some catching up to do. Me more than most . . .

Ejection seat training

“Sir,” the petite airman said while pushing my knees together, “you need to hold your knees together or you are going to lose a kneecap when your body clears the canopy rail.” Even when dealing with a gangling, uncoordinated second lieutenant, the airman was unfailingly polite and militarily courteous.

I nodded, trying better to remember my knees as well as keeping my back pressed hard against the seat back lest I break it, and my head hard against the head rest lest I snap my neck, and my elbows in as I pull the hand grips lest I lose an arm, and so on and on.

“The seat is live!” she yelled so all would stand clear. “Sir, eject, eject, eject!”

I raised the hand grips and squeezed. Nine-G’s and less than a second later I was ten feet up the rails all limbs intact. The rest of the enlisted crew did whatever it was they needed to do and my seat was lowered and I unstrapped so the next stud -- we were not allowed call ourselves students -- could get his chance at ejection seat qualification.

Much of the training for the month prior to our first flight was conducted by enlisted personnel. As a cadet in the Reserve Officer Training Corps, you get a skewed picture of who it is in the real Air Force. Our Purdue detachment had 200 cadets led by a cadre of five officers and two enlisted. The real Air Force? In 1979 that was about 95,000 officers out of a total force of just under 600,000. Of those, fewer than 5,000 were pilots. Less than one percent.

I wondered if it grated on some of the older enlisted noncommissioned officers, the noncoms. Some of these sergeants were old enough to be my parents, and here they were putting up with us snot-nosed kids trying to become pilots. They never let it show, except now and then.

Parachute training

I was being dragged across the desert floor, face down, by four noncoms pulling at my parachute straps so that I could practice flipping myself over and releasing myself from the risers. The exercise was important, I knew, because after ejecting from the airplane and landing still attached to a twenty-foot canopy, doing so would save my life.

“Lift your head, sir! Spread your legs, sir,” the senior noncom yelled while pulling, “then kick.” I did so and that did the trick. Still breathing hard from the exertion, the noncom handed me my grade sheet. “Good job, sir,” he said, “please remember to lift your head. Uncle Sam is putting a lot of money into that skull of yours. We wouldn’t want to damage it. Sir.”

I guessed it was his way of getting some of his frustration out, and I knew that frustration was justified. I thanked him and walked back to the assembly area to watch as my classmates followed in my footsteps. Due to a computer with a sense of humor I ended up as student number zero one in our class which meant I got to experience every training exercise ahead of the class. I was done first. But I didn’t get the benefit of watching others first. I think everyone who followed remembered to lift their heads.

Flight line, at last

A month later, we were flying airplanes for real. A month after that a classmate ejected from a T-37 filling with smoke, walking away from his parachute landing fall with just a few scrapes while sending his airplane into a smoking hole. Nobody was hurt, except the airplane, and we all took a moment to think about how serious this enterprise really was. “Uncle Sam is putting a lot of money into that skull of yours. We wouldn’t want to damage it. Sir.”

Our class of seventy-seven was now down to sixty-five. Several washed out for medical reasons, a few because they couldn’t hold on to their lunches after basic aerobatics, and most because they couldn’t solo. When we returned to the classroom to begin the next phase — instruments — we were a smaller, but wiser class.

Going back to the classroom after the weeks of fun in the sky was a rude shock, but it wouldn’t be our last time staring at a chalkboard.

Back to the classroom

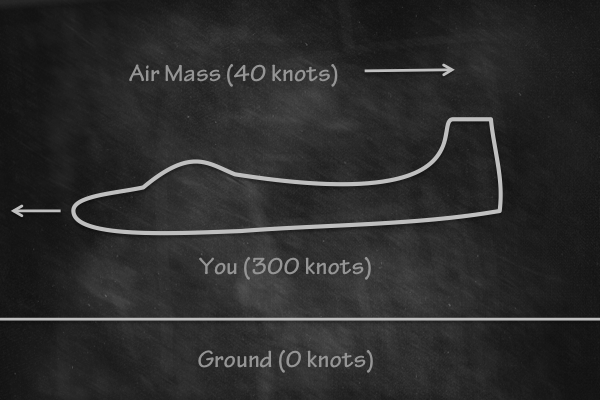

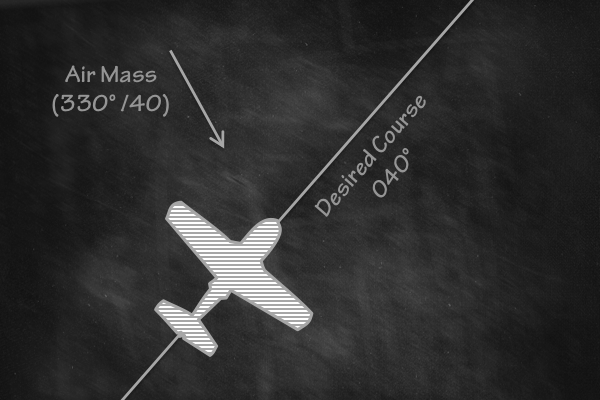

Of course it was an easy question. “260,” we all knew without need of any outside help.

“Okay,” said the instructor. He flipped the chalkboard over end-for-end. “What heading do you need to fly this course?

“Your job is to come up with exact headings,” he said, “for every leg on your flight plan. You are going to do this for every cross country flight you have and need to do this quickly and accurately.”

Of course that went without saying too. The heading would be into the wind, of course, and that meant your ground speed would decrease, which meant your en route time would increase, which meant your fuel used would increase, and on, and on, and on. These kinds of calculations were practiced by any pilot vying for his or her first license. It would appear flying a jet didn’t relieve us of this duty. What was left for us was to learn the Air Force solution. I reached for my trusty CPU-26.

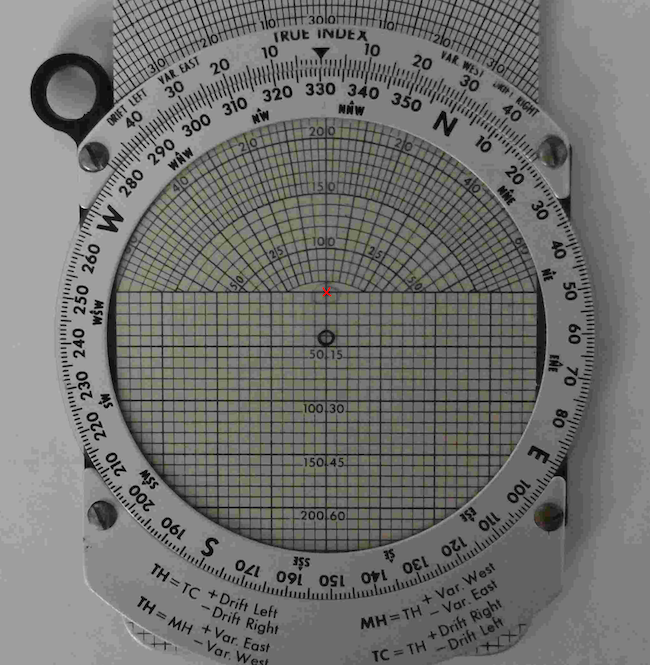

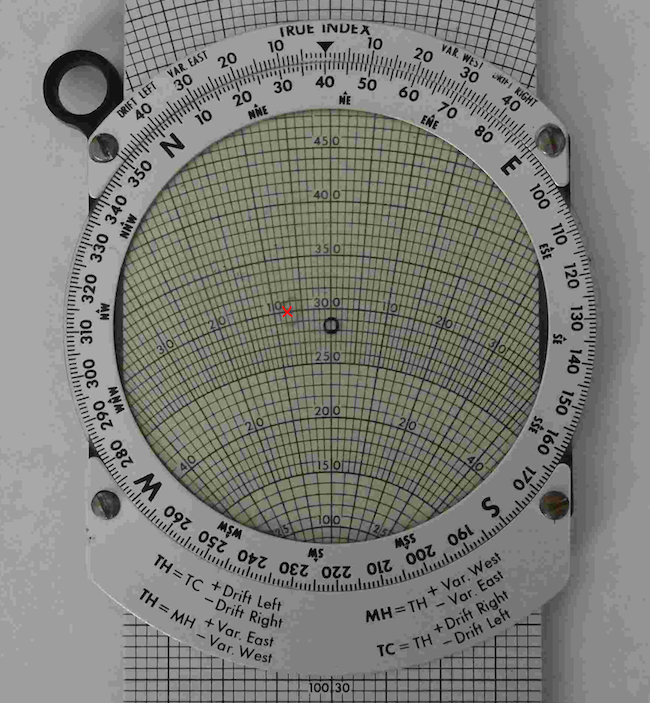

The military air navigation computer differs from what the civilians use in that it includes a two-sided slide that makes reading drift angle and ground speed a simple process. You first rotate the bezel to the wind direction, move the slide to the magnitude of the wind and mark an “x” at that spot.

Then you rotate the bezel to the desired course and move the slide so that your “x” is over the corresponding TAS. You can read your drift angle under the “x” and your ground speed over the “o” marked at the center.

“Drift is eight left,” most of us called out, “ground speed is 275 knots.”

“Anybody disagree?”

Nobody did.

“Okay gents,” he said, “be prepared to do that a hundred times on your cross country check.” In the year that was to come, we used our CPU-26 for every cross country trip and every low level mission. Flying the T-38 at 450 KTAS at 500 feet above the deck taught you quickly that getting the drift angle right was critical.

Postscripts

One year later, flying the KC-135A tanker, the navigator did all that stuff for me and my CPU-26 sat in my helmet bag, unused.

Two years later, flying the T-37B again, I got my hands on a TI-50 pocket calculator that allowed some very rudimentary calculation. In a week or so it was churning out complete flight plans in the time it would have taken me to erase the previous flight’s marks.

Three years later, flying the Boeing 707, the three inertial navigation computers did all that thinking for us. In fact, it has been that way in every airplane I’ve flown since. My trusty CPU-26 has been to every continent on earth, has flown supersonic, has cruised at FL510, and has crossed the equator more times than I care to remember. In all that time it has stayed sequestered away in a variety of brief cases, flight bags, or even a camera case or two. The only time it ventured out was on an oceanic crossing from Brussels, Belgium to Gander, Newfoundland. . . .

Twenty-three years later . . .

. . . flying a Canadair Challenger 604, I was in the left seat showing a new guy the ropes on how we made it from one continent to another without breaking a sweat. The 604 isn’t much of an international jet, we needed a fuel stop at Gander before we completed our trip to Texas.

The weather at Gander was marginal, as it often was.

“No worries,” I told the new guy. “If Gander is down, Stephenville will be up; if Stephenville is down, Gander is up. I’ve been doing this for twenty years now; that’s the way it works.”

Jeff was a better pilot than I could ever hope to be, but given his F-16 pedigree he didn’t have a lot of oceanic experience. He shrugged his shoulders and went back to his dinner.

Despite my bravado, I was watching the weather reports with greater and greater alarm. Both airports were shrouded in fog and it wasn’t getting better.

We data linked the weather for every airport in our range and things were getting dicey. On top of that, our forecast headwind of 70 knots was now at 110. We wanted to land with 5,000 pounds of fuel and now the computer predicted we would have only 2,000. I pulled the charts out and started explaining the problem with diverting across the many oceanic tracks to our south.

“It can be done,” I said, “but it isn’t pretty.”

Right around 30W, where all good things are supposed to happen, the SELCAL chimed and the right seater answered. I toggled the frequency just to listen.

“Gander reports Gander and Stephenville airports are zero, zero,” the radio operator said, “Gander requests your intentions.”

“Halifax,” I said cross cockpit. “Request direct, cross tracks, to Halifax.”

“Standby,” the voice on the radio said.

In five minutes the SELCAL chimed again and it was good news. “ATC clears TAG 55 to Halifax airport at flight level 360 via direct five three north, zero four zero west, five zero north, zero five zero west, RONPO, direct. ATC requests your ETA zero four zero west, and your ETA Halifax.”

Jeff read back the clearance as I reprogrammed the flight management system. The aircraft made a gentle turn left, about 20 degrees in heading. “This short cut is going to help,” I said happily. As soon as the new ETAs came on the screen, Jeff relayed all to Gander. The FMS now said we would have 6,000 pounds of fuel on landing. “This is good.”

We got busy with the other chores required with a mid-oceanic divert, but before long the SELCAL chimed again.

“Gander requests you say again your ETA five three north, zero four zero west.”

Jeff looked at me, I dialed up all three FMS screens to the correct page and confirmed our original ETAs were spot on. “TAG 55 verifies previously reported ETAs,” he said.

We both checked and rechecked every remaining point to Halifax. I rechecked the spelling of the airport, CYHZ. “It is all correct,” we agreed.

Again with the SELCAL. “Gander requests you recompute ETA five three north, zero four zero west. Gander believes your computations are at least ten minutes in error.”

Now there was some swearing from the right seat. “Who do they think they are,” he said, “we got the right way points and we can only punch them in so many times. What do they think, we are purposely giving them bad numbers? Jiminy Christmas!”

“Hold it,” I said, thinking maybe we had one of those queer electrons many novice FMS users claim infects all flight management computers. While I experienced my share of FMS screw ups, I knew that most errors were pilot induced. Way back when I saw my first FMS computer, in the Boeing 707, we all knew that if the computer really screwed up, you could turn it off and fly without it. The Challenger 604 and most airplanes that I’ve flown since cannot do much of anything without the computers.

“Forty West is still 200 miles away,” I said to myself, as much as to Jeff. “The FMS says we’ll be there in 26 minutes with a ground speed of 345 knots. Does that make sense?”

“Seems about right,” Jeff said, “that’s what the computer says.”

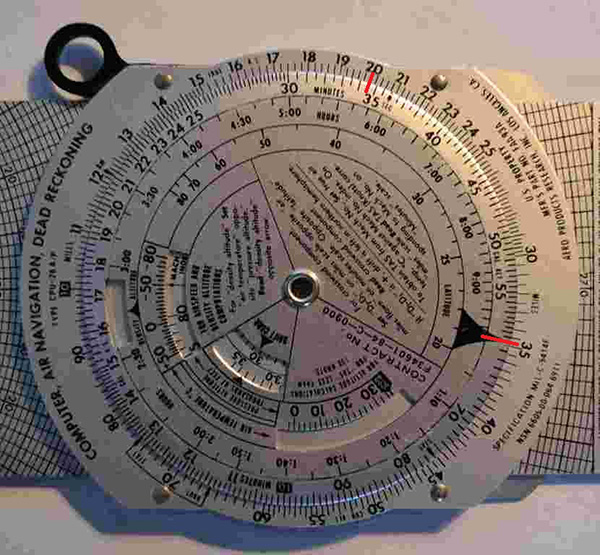

I reached for my flight bag and found Mister CPU-26. I had my answer in about ten seconds. Besides being a navigation computer, the CPU-26 is also a handy circular slide rule where distance divided by speed equals time:

The CPU-26A said 35 minutes! But there it was, right on the FMS: 26 minutes. I hit the reset on my stopwatch and watched the seconds click away as the miles to forty west decreased. “We covered six miles in sixty-three seconds,” I said while spinning the CPU-26 again, “that comes to 345 knots. The FMS ground speed is correct but the ETA is wrong. Call Gander and give them a new forty west with another ten minutes. Just a minute and I’ll get you a Halifax estimate.”

We recomputed everything manually and ended up with a fuel prediction of just over 3,000 pounds. Gander Radio was happy but we, two Air Force and CPU-26 vets, were not.

“Stinking FMS,” Jeff said, “I’ll never trust it again.” I was getting ready to agree but one of those maxims from my past popped into my consciousness.

Four Most Used Words About the FMS

From an inexperienced pilot: “What’s it doing now?”

From an experienced pilot: “Why’s it doing that?”

Chances are, the pilot is at fault. Sure, there have been more than a handful times I ended up calling the manufacturer and was rewarded with a “we’ll fix it right away” answer. But something told me this wouldn’t be one of those times. An experienced FMS user knows that, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the box is only doing what you told it to do. If the results aren’t right, the input was probably wrong.

This particular aircraft had three Flight Management Systems, each talking to the other two, comparing notes. We routinely downloaded the entire flight plan, either from a disk or from a satellite downlink. The only thing we had to do out of the ordinary was enter the winds. Our flight department SOP was to enter an average wind for the entire flight plan, not winds for each individual leg. The adult supervision in this flight department was led by a fairly lazy bunch, but those were their rules.

I thought about the things I had done as a pilot that could have made a difference and kept coming back to the winds. I pulled up the performance computer pages on my FMS and was stunned by what I saw: zero. There were no winds at all in the performance computer.

“Jeff,” I said while pointing at the screen, “I saw you input the winds, I know I did.”

“I did.” He checked his FMS and got the same result.

We both manually entered the current winds and the FMS recomputed every ETA for every waypoint and for our destination. As if by magic, everything now agreed with our manual computations.

We played with the third FMS and discovered what nobody had ever told us, and what isn’t in the FMS manual. If you change the aircraft’s destination while in flight using average winds, those average winds are dropped from the performance computer. Now we knew.

Mister CPU-26 still flies with me wherever I go. And now he gets used a little more often.