One could argue that the ability to make timely and correct decisions is an important part of just about any job. But few jobs require quick and accurate decision making routinely as a matter of life and death. We, as pilots, have just such a job. Many believe good decision makers are born, not made. There is some truth to that; the ability to make good decisions is founded in one's biology. But even with those so gifted, decision making is an art that requires practice. Poor decision makers can get better. Great decision makers can see their skills atrophy if not practiced. So how do we improve our decision-making skills?

— James Albright

Updated:

2026-03-01

If you ask someone in management school, they will tell you that decision making is the cognitive process of selecting a course of action from among multiple alternatives. It involves identifying options, evaluating possible outcomes, and choosing the one that best aligns with a goal or value. If you ask someone in aviation, they will tell you it is about making choices that impact what you are about to do. What sometimes makes an aviator’s choice different than those more ground-bound, is the time factor.

1 — Decision making with the luxury of time

1

Decision making with the luxury of time

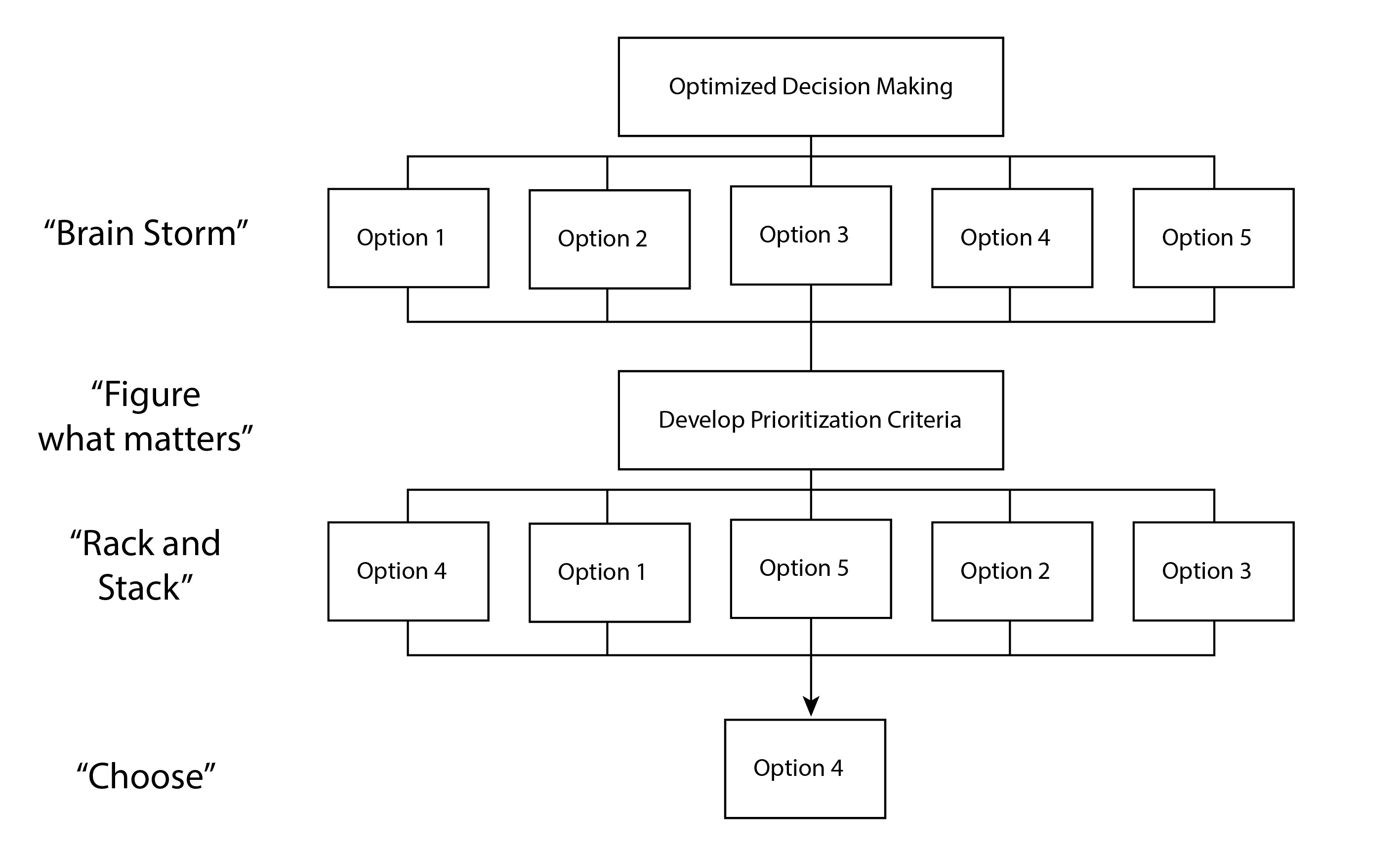

An academic in management school will tell you the best way to make decisions is to:

- State the problem.

- Brainstorm with your staff about possible options.

- Develop criteria so you can prioritize the possible options.

- Rack and stack the options according to the criteria.

- Pick the option that came out on top.

In aviation we also have opportunities for this reasoned approach, such as planning a new aircraft purchase. But even during flight, under some circumstances, there is a place for this methodical approach.

Let’s say, for example, you are en route from London, England to Boston, Massachusetts when the headwinds pick up well beyond the forecast. The winds, in fact, are beyond anything you’ve ever seen over the North Atlantic, exceeding 200 knots on the nose. You just passed 30° West longitude, and you are still 15 minutes from the equal time point between your oceanic alternates. At your current fuel consumption, making Boston is doubtful. You have a decision to make.

It would be easy to panic and rush into a decision but knowing you can deliberate for 15 minutes and still be able to reverse course and make it to an alternate should be reassuring enough to avoid a hasty decision. The conventional decision-making process may prove useful.

Some pilots like to use the acronym PIOSSEE when trying to solve complex problems:

P – Problem. Identify the problem clearly. What is wrong?

I – Information. Gather all relevant information (instruments, systems, weather, etc.).

O – Options. Consider all available options for solving or managing the problem.

S – Select. Choose the best course of action based on safety, time, and consequences.

S – Say. Communicate your intentions—to ATC, other crew, passengers, or others as appropriate.

E – Execute. Carry out the selected course of action efficiently.

E – Evaluate/ Monitor the results of your action. Did it work? Do you need to adjust?

In our suddenly strong headwind situation, you should include other cockpit crewmembers in case you forget something or to add thoughts they have outside your experience. It may be helpful to articulate the problem out loud. “The actual winds over the North Atlantic until about an hour after coast in are over 100 knots greater than forecast. We will not have enough fuel to make it to Boston with minimum reserves.” Add any relevant information you have available. “The weather in Boston is good. The weather at our Newfoundland alternate was supposed to be good but right now the surface winds are beyond our crosswind limits. If we turn around, the weather at Shannon, Ireland is good.”

Next you solicit the crew for options and offer any you might have. In the typical management school brainstorming session, all ideas are entertained, no idea is not worth considering. In a midflight situation, however, more scrutiny is needed. “We could try other Newfoundland airports, looking for one more closely aligned with the winds.” “Shannon is only three hours behind us and the conditions there are excellent.” “We could pull our speed back and get more distance from the remaining fuel.”

This scenario happened to me about 20 years ago. I first favored the Shannon option, but the flight engineer pointed out if we did that, we would be out of crew duty day and would have to spend the night, something the passengers didn’t want to do. The other pilot wanted to give the other Newfoundland airports a try, but we found quickly all of those had winds beyond our limits. Reducing our speed would help, but not enough to have legal reserves. Going back and forth – two pilots and a flight engineer – we came up with a hybrid approach no one had thought of at first. We decided to pull the speed back, refile for a landing in Bangor, Maine, and make a “go / no go” call abeam Halifax, Nova Scotia.

We let Gander Oceanic know about our situation and what we needed to do. Our plan was approved but we were warned we wouldn’t be alone if we needed to drop into Halifax, the winds were impacting more than just us. As we proceeded west, we found out the ramp at Halifax was packed and wait times for fueling were two hours or more. Fortunately, the winds died about then and we were able to reach Bangor where we refueled and were on our way in less than 30 minutes.

After we landed in Boston, we as a cockpit crew sat to debrief the long day, trying to find out why we were caught by surprise and how our subsequent decision making could have been better. There were lots of critiques to go around, the most severe in my direction. In the years I flew aircraft that needed a fuel stop in Newfoundland, I was fond of saying whenever Gander Airport (CYQX) was down, Stephenville Airport (CYJT) was up, and vice versa. This lulled me into discounting the winds report. It is a form of decision-making bias that we all need to be wary of.

2

Decision making biases

Before we dive into the topic of decision-making biases and the negative connotation of what psychologists call heuristics, let’s look at that term. A heuristic is a fancy way of saying “rule of thumb,” something people use to make decisions or solve problems without full analysis. You may hear that psychologists think of heuristics as problems to avoid, but that isn’t true. They tend to frame them as double-edged swords, efficient tools that can lead to systems biases or mistakes. We pilots tend to think of our rules of thumb as efficient tools, period. We would be wise to concoct a rule of thumb about rules of thumb: use with caution.

Characteristics of heuristics:

- Fast and intuitive

- Not guaranteed to be accurate

- Useful in complex or uncertain situations

- Based on experience, pattern recognition, educated guesses

- Subject to biases

Common biases:

- Availability bias. We often make assumptions based on examples that come quickly to mind. I can recall five windshear accidents that resulted in catastrophic crashes so I might tend to think windshears are always deadly.

- Representative bias. We might judge things based how closely they conform to a preconceived notion. I believe commuter airlines are staffed by inexperienced pilots, therefore my next flight on a regional carrier might not end well.

- Anchoring bias. We often take the first bit of information and assume it is the key bit of information. We heard that a recent crash involved an airplane that didn’t use all of the available runway, therefore that was the cause. (We later found that they back taxied and used the full length.)

- Recognition bias. We prefer familiar answers that we’ve heard before. When first given the choice of a paper approach plate versus one displayed by our avionics, we might pick paper because it is familiar and the way we’ve always done it. Then we see that the avionics offer a moving airplane symbol that greatly simplifies situational awareness.

Example of recognition bias in the context of aviation

When I started flying jets, the mystery of when to begin descent from cruise altitude appeared to be a closely guarded secret. I asked an experienced captain who told me he begins descent when the flight attendant comes forward with a hot towel. I was overjoyed when I first heard a really useful rule of thumb: “start down at three times your altitude.” While lacking details, the rule of thumb was applied by taking your altitude in thousands of feet and multiplying that by three to get the number of nautical miles from your destination. If, for example, you are cruising at 35,000 feet on the way to Honolulu, you start down at 35 x 3 = 105 nautical miles from the airport. I was based out of Hawaii at the time and most of our flying was to airports around the Pacific and it always worked. Always. Well, except for my first approach into Denver. Then the rule of thumb got me down too early. I finally realized that the elevation of the Colorado airport was throwing off the math. The new rule of thumb became: “multiply the thousands of feet to lose by three.”

3

The question of time

We’ve seen that when we have the luxury of time, decision making for aviators is much like it is for those stuck on the ground. But when time is passing quickly, things change.

In his book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Daniel Kahneman outlines two different ways to thinking:

- System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive. It operates effortlessly and often unconsciously. Two examples that he gives are detecting that one object is further away than another or adding 2 + 2.

- System 2 is slower, more effortful, and analytical. It requires focus. Two examples that he gives are filling out a tax form or looking for a specific person in a crowded room.

The obvious advantages of a System 1 process are speed and automaticity. But there are also times when a System 1 process can ignore valuable information available only if the time of a System 2 process is taken. Of key importance to us aviators faced with making decisions is that with practice, a System 2 process can be elevated to System 1. Consider, for example, the task of maintaining altitude and airspeed on a day with calm winds and no other extraneous challenges. The novice pilot will struggle with the interplay between power, pitch, and trim. After a while, the motions become automatic and require no extra effort or thought. It is to an aviator’s advantage to move as many processes into the System 1 category as possible while retaining the ability to recognize when a System 2 process is called for. We graduate System 2 processes into System 1 with practice and repetition.

System 2 processes can be lazy (they take effort, after all) and might endorse a System 1 decision without sufficient scrutiny. It is up to us to recognize when we’ve “jumped to a conclusion” based on a lazy System 2 process.

Overcoming System 1 errors and prompting System 2 corrections

While System 1 is indispensable for navigating the world efficiently, it is prone to systematic errors. We can overcome this by slowing down, using checklists, and seeking opposing views for ideas to challenge our biases.

Key takeaway for pilots: we should train and build repetitions to move System 2 processes into System 1 but keep our awareness up for when System 2 needs to take over. For example, our response to an engine failure at V1 should be an automatic reaction to keep the nose tracking down the runway, rotate at the correct rate at the correct speed, make additional control inputs to keep the airplane climbing on the desired heading. It should be a System 1 process. But we need to make room for System 2 when it comes to analyze what the problem is and what to do next.

4

Decision making when time is short

In this book, “Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions,” psychologist Gary Klein introduces the Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) Model, which I think perfectly encapsulates how highly experienced pilots make decisions when time is critical. To understand RPD, we need to remember the decision-making model preached to us in management schools and even in many flight schools: define the problem, brainstorm options, establish criteria for evaluating the options, racking and stacking the options, and then, and only then, choose the optimal option.

Recognition-primed decision making

Is that how it is done in the field? Klein studied firefighters in support of the long-held notion that they didn’t have time to weigh many options when in the heat of battle, so they only considered two options and followed the rest of the conventional model. But what he found was something completely unexpected.

One of the firefighters he interviewed claimed his Extra-Sensory Perception (ESP) saved his life. Here is the firefighter’s story:

It was a straightforward house fire in a one-story house in a residential neighborhood. The fire was in the back, in the kitchen area. The lieutenant sent his hose crew into the house, to the back, in order to spray water on the fire, but the fire just roared back at once.

“Odd”, he thought. The water should have more of an impact. They tried spraying it again, with the same result. They retreated into the living room to regroup.

Then the lieutenant started to feel that something was wrong. He didn’t have any clues; he just didn’t like the idea of staying inside the house and ordered his men out of the building – a very average house.

As soon as the men left the building, the floor they had been standing on collapsed. Had they stayed inside, they would have been plunged into the flames below.

Klein, pp. 32 – 33.

The firefighter was convinced it was ESP that saved the day, and his men took that as given. How could they not? Klein probed further.

The firefighter’s experience pattern wasn’t agreeing with the situation. The event wasn’t unfolding as his experiences would have dictated. He didn’t know there was a basement, he didn’t know the fire was actually under the living room where he and his men were standing before they left. The living room was hotter that they would have suspected for a kitchen fire. Fires are usually noisy and for a fire to be this hot, he would have expected more noise.

In hindsight, the events were obvious. In the heat of the moment, it wasn’t making sense. His reaction was to withdraw. He didn’t ponder, he didn’t consider his options, he just made the decision. It was his accelerated decision-making — and not ESP — that saved the day.

Klein, pp. 32 – 33.

Klein argues that when armed with enough experience, our brains will match the events with an internal database to select an option to react as quickly as possible. If the decision-maker has enough experience, he or she will then simply consider if the option is feasible, and if it is, act. Note that the decision may not be the best choice, but if time is taken to come up with the optimal decision, it could be too late. There isn’t enough time to make it perfect.

Example after example proved to Klein that experts at dealing with time critical decisions didn’t use the conventional brainstorming / rack and stack method. Instead, they:

- Recognize a situation based on experience.

- Match the situation to the response that “seems” right.

- Mentally simulate the consequences of that action.

- Act, often without considering other options unless it seems wrong.

I once lost an engine right at V1 in a Boeing 707 taking off from Dallas Love Field (KDAL), Texas, where the airplane had been in maintenance for nearly a year. The oil pressure on Number 3 went to zero. I rotated, got away from the ground, and shut the engine down. I asked the copilot to get us immediate clearance to Carswell Air Force Base, just a few minutes away. Once cleared, the copilot suggested a holding pattern so we could catch up on checklists and consider our options. I looked at the engine instruments and something was wrong. With three operating engines and one shut down, I expected to see three rows of needles pointing in the same direction, but the needles were pointing in random directions. “The only checklist I want is the before landing checklist and the only option I want to consider is putting the airplane on the ground.” Five minutes later we were on the ground. An hour later the base’s chief of maintenance said we were only minutes away from losing at least two more engines. It seems the fuel, hydraulic, and oil connections on each engine were fastened only hand tight. The copilot was convinced I had a secret connection with the airplane, and I started wondering about that until I realized it was those mismatched engine gauges.

Some would call this intuition, and I think they are right. That begs the questions: what is intuition and how can we improve it?

5

Intuition

Many of us in the technical fields – like operating airplanes – tend to have a negative view of the word “intuition.” It makes us think about “feelings” and things that don’t go well with physics and the hard sciences. But is that true? What is intuition anyway?

Intuition. Noun. A natural ability or power that makes it possible to know something without any proof or evidence, a feeling that guides a person to act a certain way without fully understanding why.

Merriam-Webster

This is the classic dictionary definition, but medical science has come some distance since Webster thought this one up. There is physiology and neuroscience to suggest we can delete the words “without any proof or evidence.” While a discussion of this is beyond our scope here, I’ll leave references at the end of this chapter for additional study. My conclusions from reading these references:

- Scientists around the world have come to realize that there is hidden machinery in our brains that collect huge amounts of data, maintain a database of decisions that exceeds our conscious memory, detects errors, and makes decisions in fractions of seconds.

- While this supercomputer sounds too good to be true, it has its flaws: it doesn’t communicate with you in obvious ways, it can be fooled, and it atrophies from disuse. The good news is that it is all automatic. You just have to train it with the right data in a way that data gets stored. But how do you do that?

- The orbitofrontal cortex appears to be key. “Orbit” is Latin for eye socket and the orbitofrontal cortex is the part of the brain that sits right behind the eyes. Cancer patients who have the orbitofrontal cortex removed all suffer from the same affliction. While they don’t lose any cognitive ability, they all lose the ability to make decisions or feel emotions.

- It appears emotions are linked to decision making. It’s not that emotional people make better decisions, clearly that is not true. But it seems that decisions may produce emotions.

- The anterior cingulate cortex is closer to the brain stem which tells us it is closer to our more primitive functions. It does things like regulate our blood pressure and breathing. It is also the part of the brain that records experiences, anticipates, and regulates our emotions. It is thought to assess all inputs against an internal database and detects patterns too subtle for you to consciously detect. If it observes something that agrees with or disagrees with its database, it generates an emotional response. But the database has to contain experiences already registered.

- That’s why champion level chess players, poker players, and quarterbacks who spend hours obsessing over past mistakes tend to succeed. Their anterior cingulate cortexes remember and when a mistake is about to be repeated, a subconscious emotional response tells the conscious there is a problem.

In the case of Klein’s burning house example, the firefighter captain had been in many house fires and knew intuitively that kitchen fires are loud and hot. Since the fire wasn’t as loud as he thought it should be, nor as hot, he knew something was wrong and decided to withdraw. He didn’t know the house had a basement, where the actual fire was, but he knew the situation didn’t comport with his experience. Even after the floor where he had been standing collapsed into the fire, he still couldn’t explain how he knew to withdraw. Klein concluded that his career’s experiences with house fires logged into his subconscious and was available to use when he needed it.

When an experienced captain elects to delay takeoff when his younger first officer sees no reason to do that, it may very well be the captain has lived the experience before and knows caution is called for. The captain may not be able to explain why, but his or her anterior cingulate cortex has logged away the experiences and raised the red flag. The captain is wise to take that counsel.

Improving intuition

In “Sources of Power,” Gary Klein offers several ways to develop what he calls “expert intuition.” Aviators will recognize many of the steps as a part of normal recurrent training but may not appreciate the value to developing intuition.

- Purposeful practice in a specific skill, with immediate and consistent feedback. Malcolm Gladwell is often credited for the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of focused practice to achieve mastery in any field, based on a study by Anders Ericsson. As it turns out, Ericsson never said this. In his book “Peak: Secrets from the new science of expertise,” Ericsson says that practice that doesn’t include a deliberate effort to improve does not lead to improvement.

- Build unconscious pattern recognition by providing your brain with more and more high-quality examples. That’s why studying accident case studies can be so impactful.

- Expand your tacit (unconscious, experience-based) knowledge by reading widely, talking to experts, and studying a wide variety pertinent case studies.

- Train your body’s interoception, or physical awareness. Muscle memory doesn’t teach your hands how to fly an ILS, for example, but it teaches your brain to guide your hands to do just that.

- Reflect and evaluate your intuition. After you’ve made an important decision, ask yourself what cues led to the decision, how did the decision work out, and why? You can learn from wins and losses, but you have to make the effort to evaluate the results.

The bottom line about improving your intuition is that repetition of task-specific training has more value than is at first evident. “We’ve done this a hundred times, why do we need one-hundred-and-one?” It turns out, every additional event has additional value, whether that is obviously apparent or not.

The bottom line on decision making is that deciding quickly or deliberately depends on how much time you have. Your quick decision making will be better if you’ve spent the time to train your intuition.

References

(Source material)

Bechara, Antoine, etal. Emotion, Decision Making and the Orbitofrontal Cortex. Department of Neurology, Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA 52242, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

Kennerley, Steven W. and Walton, Mark E. Decision Making and Reward in Frontal Cortex: Complementary Evidence From Neurophysiological and Neuropsychological Studies. Behavioral Neuroscience, 2011, Vol 125, No. 3, 297-317.

Klein, Gary. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1998.

McCraty, Rollin, etal. Electrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 1. A System-Wide Process? The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, Volume 10, Number 2, 2004, pp. 325-336.

McCraty, Rollin, etal. Electrophysiological Evidence of Intuition: Part 2. The Surprising Role of the Heart. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, Volume 10, Number 1, 2004, pp. 133-143.