If you really want to know the science behind airspeed measurement, you should look at Properties of the Atmosphere.

— James Albright

Day one with ICE-T

In 1979, the U.S. Air Force conducted Undergraduate Pilot Training—UPT—at five bases throughout the desert southwest. UPT was where second lieutenants were turned into real jet pilots, or were killed or washed out trying. The program lasted 48 weeks and began with a month of academics and ground training, was followed by 4 months in the Cessna T-37, and was capped off with 6 glorious months in the Northrop T-38 Talon. Day One for me was on Tuesday, January 2nd.

A second lieutenant shows up to UPT with a lot of baggage, emotional baggage. The Air Force pinned cadet wings on me when I was eighteen: the promise that if I managed to survive the next four years, I would get my shot at turning those tin wings in for a real set of Air Force wings. I spent those four years at Purdue University with two-hundred other cadets, only a fraction of whom had those coveted cadet wings. We pilot cadets wore them with pride and did everything we could to immerse ourselves in the culture. “If you ain’t a pilot,” we would sing at our weekly beerfests, “you ain’t shit.” Of course we ignored the two obvious problems with our braggadocio. First, we weren’t pilots yet. Second, the logical counter to the statement was: if you were pilots, you were shit.

For four years we talked and dreamed aviation. In our dreams we were pulling those unbelievable G-forces, skirting the floor of the desert at six-hundred knots, slipping the surly bonds of earth just inches away from our wing man as we reached out to touch the face of God. But in those dreams, we were the aircraft, not the pilots. None of us had the slightest idea of the mechanics behind making the supersonic jet bend to our wills. It was all still just a dream.

And there was more baggage than the good stuff, though none of us were able to dwell on the bad: washout. The Vietnam War had ended and the military was flush with returning pilots. The Air Force and Navy were throttling way back on pilot production. Three-quarters of all cadets with pilot training slots lost them. Half the UPT bases were closed. And the washout rates were going up. During the war years, all sins were forgiven and anybody who could keep the airplane in one piece with a small amount of style would get their wings. Now, we heard, you couldn’t sneeze the wrong way without washing out. With the decreasing need for pilots came an increasing wait for pilot training. For me, the delay was seven months of looking forward to the day I could dance the skies on laughter-silvered wings.

Then the day came. It was surreal: putting on the uniform, the light blue shirt, dark blue pants, and epaulets with the single gold bar on each shoulder. For me, it was my first day in uniform since the day I was commissioned and my dad pinned those bars on my scrawny shoulders. Now I was walking into the flight room — my first flight room of many to follow — with seventy-six other officers, most of whom were also second lieutenants. Most of those looked like teenagers, too young to be officers. Not like me, a more manly twenty-two years old, six feet tall, one-hundred-fifty-five pounds of pure, fire-breathing testosterone.

They split our class into two flights, I was a part of “No Loss” and was issued four flight suits and four flight patches to sew on the right sleeve. On the right side of our chest we placed the Air Training Command patch and on the left, where the wings belong, a plain blue patch with only our names. Our flight commander was an ex-navigator captain with four years of surly bond slipping of his own, albeit from the back seat of an F-4. He knew what is was like out there.

“These blue uniforms are bullshit,” Captain Ron said to us when we had our first meeting together, “pilots wear flight suits.”

“Damned straight,” we said as one.

“Tomorrow we show up in the green bag,” Ron continued, “to hell with regulations, to hell with instructions. You want to be pilots?” He let the question hang. “Then act like pilots!”

So on day two, against all instructions, our flight showed up to class in green bags, ready to fly. We wouldn’t touch an airplane for a month, but we were ready. Our instructor strolled in and somebody called the room to attention. From the corner of my eye I could see he was surprised by our uniform choice, but he quickly recovered.

“Flying airplanes,” the instructor began, “is one percent hands, nine percent brains, and ninety percent attitude.” At the time, I thought it was all motivational mumbo jumbo. In time, I would learn, it was true. “Today we start building on that nine percent, so get ready to memorize.” He turned his back to us and wrote the first lesson:

He explained that in the cockpit, the most important number for keeping us flying was airspeed. Of course, even on day one, we knew that. But that speed—Knots Indicated Airspeed (KIAS)—was only the beginning.

IAS—Indicated Airspeed (what we see on the instrument)

CAS—Calibrated Airspeed (IAS corrected for installation errors)

EAS—Equivalent Airspeed (CAS corrected for air compressibility)

TAS—True Airspeed (EAS corrected for air density)

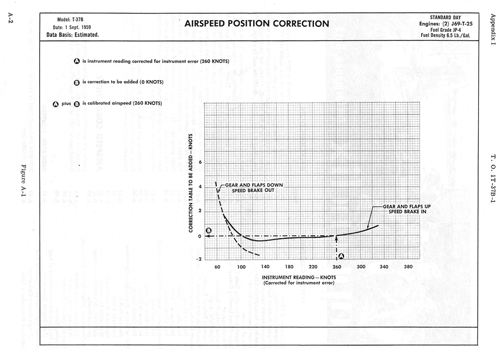

“Your airspeed indicator gives you indicated airspeed,” he said without a hint of humor, “it was built by the cheapest bidder and it wasn’t built for the Tweet. It was built for a generic airplane so you have to correct for that error. Turn to page A-2 of your dash ones.”

We all pulled out our brand new flight manuals. Mine was already removed from its plastic wrapper and placed into its binder with all the tabs correctly inserted. I read the thing cover-to-cover overnight. The more macho in the group started to pull the plastic wrap from their untouched bundle of books.

In a few minutes we all had the correct page.

“I wrote the ‘C’ slightly higher than the ‘I’ because it usually is slightly higher. As you can see from the chart, for most conditions the installation error is between zero and two.”

I wrote down “installation error 0 - 2” as I heard some muffled laughter.

“Who gives a shit,” I heard from a fellow stud. There was more laughter.

“Exactly right!” said the instructor. “You can’t read 2 knots on the indicator, so who gives a shit.”

“What about the ‘E’ that comes next?”

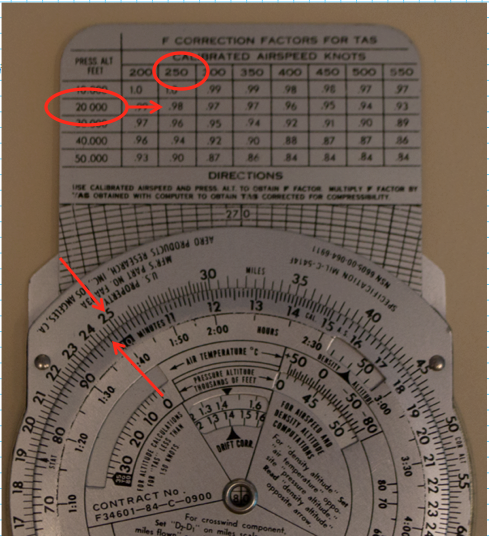

“F Factor,” somebody said. My peers were smarter than I was; I needed to catch up. F Factor was what the Air Force decided to call compressibility effects.

“So if we are at 20,000 feet, what is our EAS?”

The CPU-26 had a chart on one side that showed us the F-Factor was 0.98. Since EAS was drawn lower on the chalkboard, it stood to reason the answer was 0.98 times 250.

“245,” I said, solo.

“Very good.”

“Now what about TAS?”

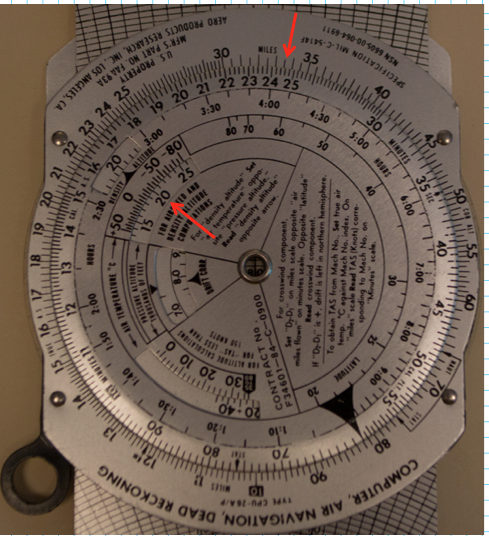

Nobody knew that one. He led us through the procedure with our CPU-26 computers.

“What’s the standard temperature at 20,000 feet?” One of the guys in the front row knew that:

Standard Temperature is 15°C minus 2°C per thousand feet above sea level, until 36,000’ after which it becomes constant at -56°C.

Which meant the standard temperature at 20,000 feet was 15° - 2(20) = -25°C.

At the front of the class the instructor had a six foot tall CPU-26 and he moved the inner circle as we all mimicked his actions on our own circular slide rules.

Placing the OAT—outside air temperature—opposite the PA—pressure altitude—yielded a density altitude of 20,000. Of course, that made sense, we used standard temperature. Then it was just a matter of reading the TAS off the outer scale opposite the EAS:

“335,” he said with finality. “Everyone get that? So while your airspeed indicator says 250 knots, you know the airplane is actually going 335 knots through the air.”

That was a pretty neat trick, I had to admit. Figuring TAS all the way from IAS using nothing but that little CPU-26 piece of tin.

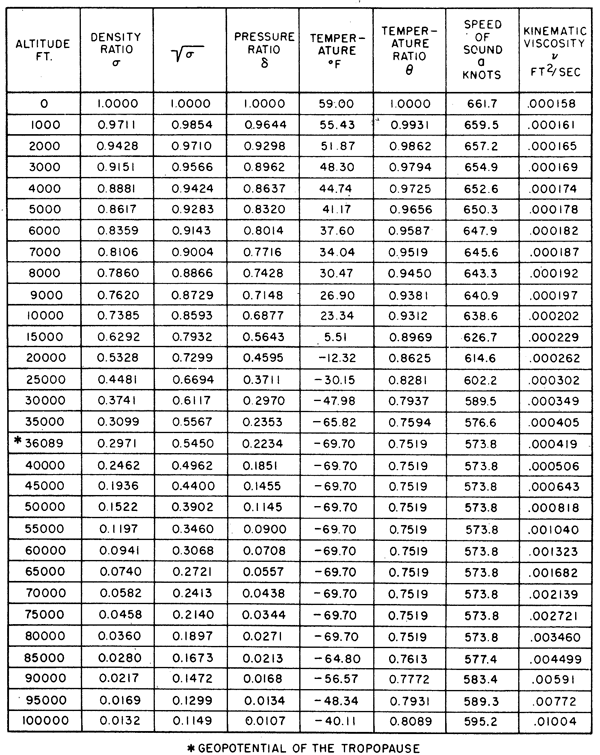

That night I brought out my favorite aero book and did it the old fashioned way, starting with the standard atmosphere table:

I knew the formula, the hard way:

TAS = EAS ( 1 / √(σ)

= 245 ( 1 / √( 0.5328) )

= 336

I decided the CPU-26 had earned a place by my side in any cockpit.

Postscript

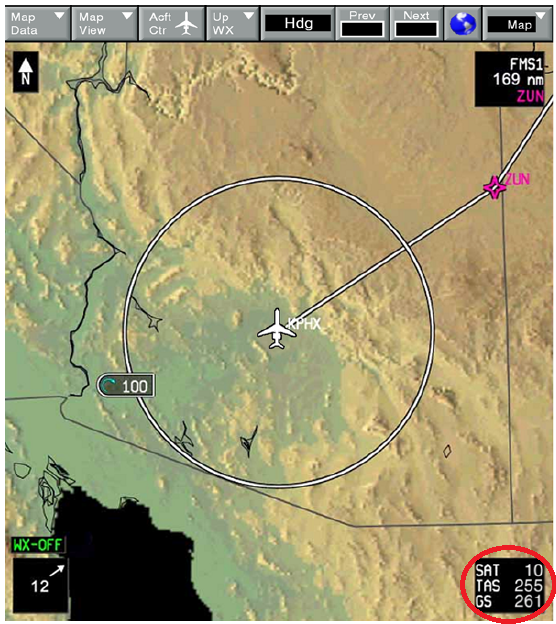

Forty-eight weeks later, my wife pinned a set of Air Force pilot wings on my chest. Six years later they were replaced with a set of senior pilot wings, the same wings with a star on top. Seven years after that, that star was circled with the wreath of a command pilot. After twenty years, those military wings were retired for civilian wings and so it goes. The CPU-26? It still travels with me, though it rarely gets used. The airplane du jour does all that ICE-T automatically: