It may be true to say getting into a spin is losing control of the aircraft, for most aircraft. But most aircraft are designed to virtually get themselves out of a spin — that is, if the pilot does nothing the aircraft solves the problem for you. (Center the controls, no more spin.) The T-37 was not such an airplane, once you got it into a spin, it was designed to spin itself into the ground unless the pilot did something to correct the situation. More about spins: Spins. Video about: T-37 Spins

— James Albright

I showed up at Air Force pilot training with a little bit of fear and a lot of humility; those are two ingredients no military student pilot should have. Even the term student pilot is banished from the vernacular. At age 22 I was not permitted to think of myself as a student, I was a stud. I was a stud assigned to "No Loss," one of several T-37 flights.

Fear? I suppose that was normal. Though it was a foreign concept those days, back then there was a sizeable death toll in Air Force pilot training. In the year to come we would lose four. But that wasn't the fear I was experiencing. No, it was a larger fear than death. It was the fear of washing out of the program. Undergraduate Pilot Training was the only school in the Air Force you could fail and not have a black mark placed on your permanent record. Not anyone could survive the fifty weeks to come.

Humility? That was the Air Force's doing. Williams Air Force Base was the one good UPT base, all the others sucked. Willie was near Phoenix. All the others were in the worst desert locations in Texas or Oklahoma. Willie was almost entirely reserved for the Air Force Academy, the Zoomies. They did keep three slots per class for unwashed ROTC graduates. I would be sharing the next year with those from the exalted mountains of Colorado Springs.

Not that I didn't know better. As a junior cadet I spent a month flying the F-4 at Seymour Johnson with ten Zooms. They were human. In fact, they were a bit sub-human. Still, this would be a year of living with a class of officer the Air Force clearly thought superior to us that attended real colleges. My table mate in T-37's would be the first Zoom I would really get to know.

The first flight was the dollar ride - so called because it was just like a carnival roller coaster. The instructor let you try every maneuver in the book, from high-g loops, chandelles, and even the infamous inverted spin. Or you could go out and have a lazy day in the aerobatic maneuver area. It was up to you. You paid your dollar and you got a carnival ride. It was to be your last time in the year where everything you did wasn't graded.

"How'd it go?" I asked Roger who had the honor of the first ride between us.

"I puked all over the instrument panel," he said quietly, "it was a blast but my stomach couldn't take it."

Then came my turn. "Did you throw up?" he asked.

"I wanted to," I admitted, "but half the time I didn't know which way was up."

In truth, I held on to my lunch and Roger appreciated my gesture. "Between you and me," he said, "we keep things civil, okay?"

"Of course," I said, "you don't even have to say that."

"You don't know these guys," he said, "I spent four years with them. It isn't funny unless it's cruel, and there's lots to be cruel about."

After our first week flying the Tweet we lost three guys to "manifestations of apprehension," the flight surgeon's way of saying fear of flying. In another week there was a fourth, but after that the casualties all came from performance in the jet. After a month we lost a few who couldn't solo — manage to fly the airplane by themselves — and all of us survivors began to walk with the swagger of real jet pilots. From this point on, much of our flying was solo.

"So there I was," one of our classmates said at our morning briefing, "just falling out of a loop in the high area, pointing straight down, and what do I see? It was another Tweet flying straight and level in the low area!" It was our morning chance to give the flight lessons learned from the previous day at the end of which a travelling award would go to the biggest dufuss of the flight. The award was a five pound can of cured ham, on top of which was a brass plaque: "No Loss Ham Hands." There was no worse insult, being a pilot with two hands with no feel for flying; hands named Armor and Star.

"I was wondering," the lieutenant continued, "what kind of a stud would waste all that jet fuel on flying straight and level? Hell, if you wanted to do that you could have joined the Navy!"

We roared with laughter.

"So I followed the future airline pilot home thinking it was one of those wankers from another flight, but no! It was one of our own! Right Kevin?"

We all turned to face the straight and level stud. Kevin blushed and nodded. The flight commander scooped up the can of ham and placed it squarely in front of Kevin, where it would stay until someone else embarrassed himself further.

"You and me," Roger whispered, "will never do that to another stud. Deal?"

"You got it," I agreed. Roger was one of the good Zooms.

At the end of the second month most of the class had passed their first check rides but the stragglers were starting to wash out. Your reward for passing the first check ride was your introduction to formation flying, the most fun any pilot would ever be allowed to have. It was difficult for the stragglers, because they were still concentrating on basics while the rest of the class was reliving their intros to pure military aviation. I tried to contain my joy whenever I saw Roger.

"Okay," he said, "why can't I do this?" He had busted his check ride and his recheck. One more and he was out.

"Geez, Roger," I said, "you can do this. You just need to have the spin recovery memorized cold and you'll ace it."

"I know the recovery," he said, "I just can't do it!"

"Okay lieutenant," I barked while throwing a pad into his chest, "give me the spin recovery, now!"

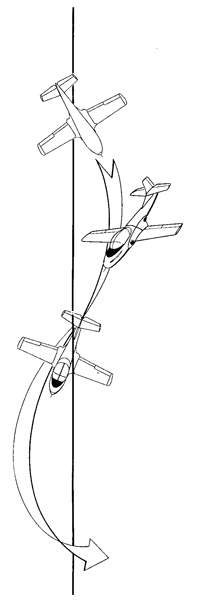

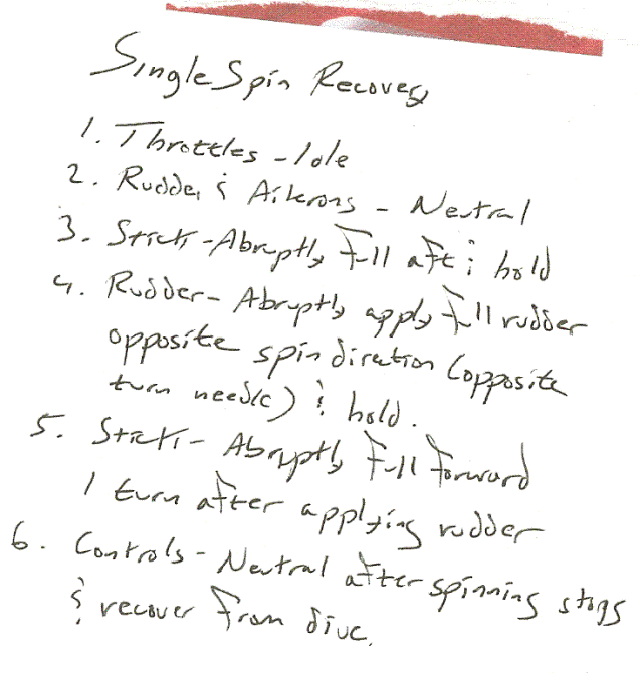

Roger sat down and wrote. The single spin recover was six steps, thirty-nine words, six dashes, and four ampersands; in a precise order. We were told that when placed in the proper order, those thirty-nine words would get any aircraft out of a spin, unless the spin was unrecoverable. You couldn't pass pilot training without mastering the procedure.

Roger's written work was flawless. I pushed him into his seat, pinned his arms forward. "Okay, close your eyes and talk me through it. You bring the nose up to about sixty degrees of pitch and a slight bank, you get the stall and hold the stick steady and wait for the rotation. The nose pitches down and now the world is spinning. Now the nose is up again, now it's down again. Recover."

"Throttles Idle!" Roger says pantomiming the imaginary levers to their aft stops.

"Rudder and ailerons," he says, fumbling with the imaginary stick, "ah, neutral. Stick . . ." now he was hyperventilating, "stick abruptly . . ."

He just couldn't get the words out. And this was sitting at our flight room table with his chair firmly planted on terra firma.

"Do you have to say the words," I asked, "as you are doing them? Can you do them silently?"

"No," he said firmly, "otherwise I'll get them wrong."

I let it drop. I knew that most guys did annunciate all thirty nine words. I was and still am a slow talker, so if I were to do that, the airplane would have made a tidy hole in the desert before I got to the first ampersand. But flying was all about confidence. I couldn't shake whatever confidence Roger had and, besides, he wasn't a slow talker. He was a nervous talker.

A week later Roger was gone. I heard he had a degree in engineering and ended up in a civil engineering squadron. I bet he made a good Air Force engineer.