In the venerable old KC-135A, we used to plan our weights so that we would clear all obstacles in the event of an engine failure, barely. "Make it so we scrape paint," we were told. The lessons were valuable, of course, but the objectives were foolish. TERPS, 14 CFR 25, 91, 121, 125, and 135 all have more to say on the matter and you could do worse than to study Departure Obstacle Avoidance.

— James Albright

Updated:

2012-01-21

Day One of tanker school. I had never even heard of the KC-135A before. It was a Boeing 717, the precursor of the Boeing 707, built with extra skin and smaller engines. I turned down my first assignment from pilot training, was hanging around waiting for the next, and a massive drug bust at Loring Air Force Base in Maine sent me and twenty or so other brand new pilots to tanker school. No matter, an airplane is an airplane. Or is it?

It was, for someone graduating flying a 12,500 pound rocket, a massive and under-whelming airplane. It grossed out at 297,000 pounds but its four engines only produced 9,500 pounds of thrust. You could boost each engine another 3,000 pounds by injecting de-mineralized water. But even so boosted, the performance was anemic. Getting the thing off the ground was only half the battle.

“Climb performance,” the crusty old instructor said, “is feet climbed vertically divided by feet traveled horizontally.”

Rocket science it wasn’t. But the numbers were alarmingly low.

“If you lose an engine,” he continued, “all this goes out the window and then you all you need to do is scrape the paint.”

I would hear that many times over the next two years — I flew that thing for 22 months — you found the highest obstacle in your flight path and limited the gross weight so as to just barely clear it. It was a lie, of course.

Air Force pilots tend to be a macho sort. Fighter pilots back then took pride in either: the fact their aircraft could out-fly anything else in the sky, we had the brand new F-15 back then; or were so dangerous that even without an enemy they were likely to kill you, the F-4 comes to mind. But even tanker pilots had a machismo of sorts, a pride in flying an airplane so underpowered and with engines that so often blew themselves into metal shards, that it would take nerves of steel to even contemplate a takeoff. From the school house to the operational line, tanker pilots told you losing an engine on takeoff meant death unless you had superhuman skills. It happened to me twice in that aircraft. I don’t have superhuman skills and I am still here to brag about it. What gives?

There are two issues to consider: pure climb performance and obstacle clearance.

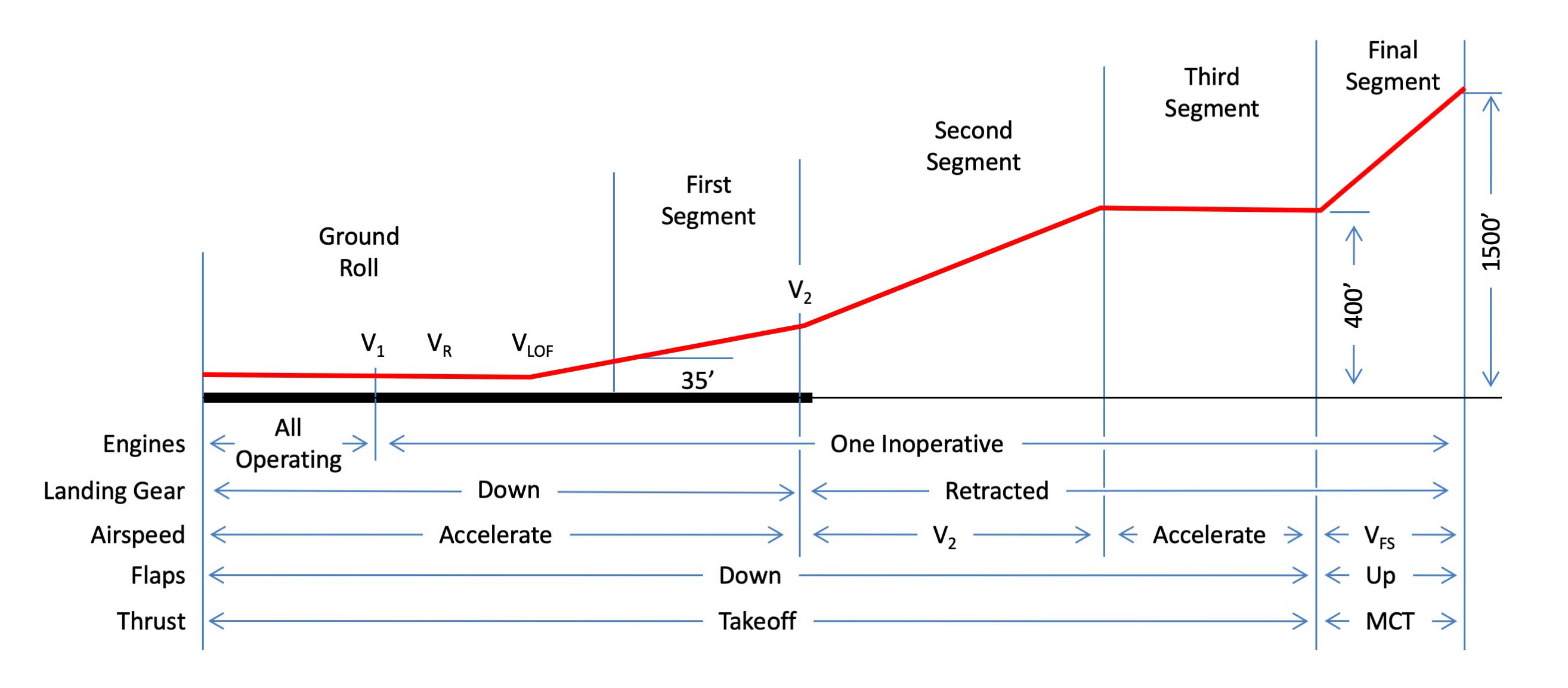

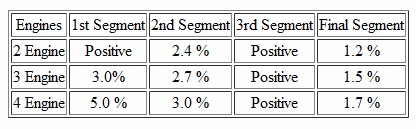

The FAA regulation that covers pure climb performance — the ability to takeoff without consideration of obstacles — is what we call today 14 CFR 25. Back then it was FAR 25. It states that a four engine airplane with an engine failed has to meet or beat the following:

- 1st Segment: 5.0%

- 2nd Segment: 3.0 %

- 3rd Segment: Positive

- 4th Segment: 1.7%

A fully loaded tanker on a hot day met all these requirements, just barely. The first time I lost an engine on takeoff in a tanker, it was fully loaded on a hot day in Guam. We spent a long time in the third segment trying to accelerate. But accelerate we did.

Obstacle clearance is where the so-called paint scraping comes into play. Here is where we copilots spent a lot of time in the books and we tanker pilots thought of ourselves as steely eyed bags of testosterone. It was a false bravado.

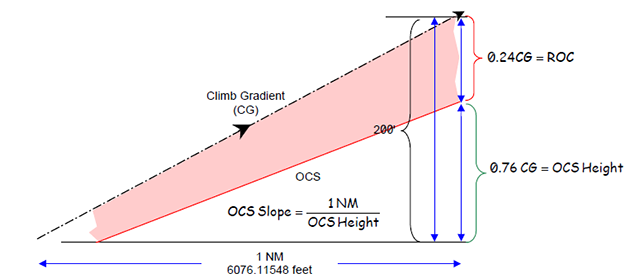

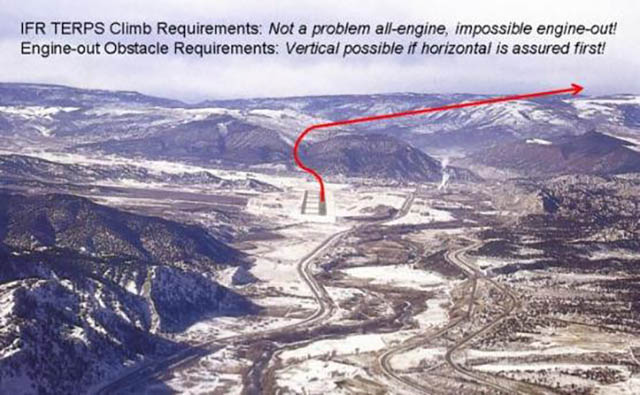

The Air Force calls it AFMAN 11-226. The Navy calls it OPNAV INST 3722.16C. The FAA calls is 8260.3B. But no matter whose version you’ve got, it is also known at the United States Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures, or TERPS. The civilians use it to determine all-engine aircraft performance. The tanker community was using it to define engine-out numbers. We were being conservative. TERPS gives you a minimum climb gradient of 200 feet per nautical mile which must include at least 24% clearance over all obstacles. We were hardly scraping paint, we were clearing obstacles by:

Clearance = Minimum climb rate x Required Obstacle Clearance

= 200 x 0.24 = 48 feet per nautical mile

TERPS was intended to provide all engine performance criteria. We were meeting these with an engine failed. Conclusion: if we made it off the ground, the obstacle wasn’t going to be a problem.

Postscript

Ten years later, flying the Boeing 747, we had performance to spare. An FAA-certified aircraft, we had to meet TERPS with all four engines running and 14 CFR 25 with an engine failed. And we did.

Fifteen years later, flying a Gulfstream III, performance was again not a problem.

Twenty years later, flying a Challenger 604, performance was a big concern because we didn’t have any. The airplane could get off the ground okay, but clearing obstacles was often a limiting factor. We often looked for a way to thread the needle.

Thirty years later, back in the Gulfstream (IVs, Vs, and the 450), performance was easy again. Two-engine requirements are a bit less than four-engine:

Gulfstreams, however, don’t use 3rd of 4th segments because they can sustain the higher 2nd segment numbers all the way to 1,500 feet. Excess power is good.