When you are twenty-six you can go a long time without sleep and start to think you are invincible. Then, if you are lucky, you get scared without breaking anything or hurting anyone.

— James Albright

A lesson in misplaced trust.

October 1981

It was my last full day on alert at Loring Air Force Base. After twenty-two months in this Godforsaken place, I had orders back home to Hawaii. Well, I had verbal orders. The written orders were still waiting my commander's signature. For some reason, Lieutenant Colonel Howell wasn't willing to sign them. The movers were coming next week but threatened to cancel if I didn't have written orders in hand. I was starting to worry.

I preflighted our alert tanker for the last time, checked my Emergency War Order gear for one last time, and slowly walked to the alert truck to avoid slipping on the ice one last time. As I closed the door behind me the aircraft commander and navigator were talking about the latest squadron controversy: the officer's club.

"Can you believe it?" The navigator was incensed. "Our squadron has five officers who aren't members of the O'Club. I thought that kind of stuff was basic. Five!"

I kept silent. The nav didn't know that I was one of those five. In a squadron of over a hundred officers five rebels wasn't too bad. The real question, in my mind, was did my boss know I was one of those nonconformists?

"Well that's all Howell talks about these days," Major Long said, "I guess our squadron's name is up in lights because we got more slackers than anyone else."

I guess he didn't know I was a slacker. I needed to change the subject. "Any words on my orders, sir?"

"Nah, he told me he was too busy but he'll eventually get to them. How in the hell does a mere lieutenant get out of here in less than two years?" It was a rhetorical question, of course. Major Long knew the answer. The Air Force still considered Hawaii a remote assignment that people wanted to avoid. Any officer considered a resident of Hawaii, Guam, or Okinawa got preferential treatment getting assigned back to their homes. I interviewed with the special duty assignment squadron there, they said yes, and now I was leaving the frozen north for good. Once Colonel Howell signed my orders.

Not that Loring was a really bad assignment. It wasn't. In less than two years I logged nearly six-hundred hours of four-engine jet time in the KC-135A tanker, and another six-hundred in the T-37B "Tweet." I had flown down to instrument minimums more time than I could count, been all over the world, and learned what could kill me and what could keep me alive in just about any cockpit. Not a bad deal for having to put up with all this %$#@! snow.

"I think the ceiling is coming up," Major Long said as we pulled into the alert facility. "Maybe you'll end up flying tomorrow after all."

Indeed. Today was to be my last day on alert and tomorrow my last trip in the T-37. I was scheduled to fly with Captain Russ Rider, my office partner at Wing Standardization and Evaluation. We were both tanker copilots on stan/eval crews. Russ gave check rides in the base simulator and I wrote evaluation forms for these and the flight checks given by our evaluator pilots and navigators. I'd never flown with Russ, but he was a good guy and I was looking forward to a few days on the road with him.

I walked through the alert facility to our stan/eval office on the opposite end. On my desk there was the normal collection of handwritten check ride forms waiting for me to type out the official Air Force Form 8 evaluation records. Opposite my desk was Russ's desk, strewn with en route charts for tomorrow's flight. It looked like we would be darting around the northeast and ending up at Plattsburgh, New York.

After my third Form 8 Russ came in, throwing his hat on his desk and himself into his squeaky leather chair. "Where you been?"

"O'Club," he said, "I just got the talkin' to of my life," he said, "officership, professionalism, all that. Now I gotta pay eight dollars a month for a club I never go to."

"They can't order you to join, it's against the regs. You don't have to be a member of the O'Club."

"Yeah, but they can make your life a living hell until you do."

So Russ caved. "Now there are only four of us left," I said. "You coward!"

"Brave talk for someone with FIGMO."

"FIGAMO," I corrected, "I don't Got my Orders yet. Howell refuses to see me. I heard he has them but he is too busy."

"Yeah, sure he is."

By lunch time my paperwork was done and our T-37 trip was completely planned. It was going to be a long day. From Loring we would fly down to Pease Air Force Base in New Hampshire, Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, Dover Air Force Base in Delaware, Rochester New York, and then Plattsburgh Air Force Base in New York to spend the night. Four hops in the unpressurized T-37 strapped into an ejection seat and breathing from an oxygen mask wasn't the easiest way to log time, but the Air Force allowed us to fly 6.5 hours a day and that was what we were going to do.

"Lieutenant Albright," the secretary called over the intercom, "Colonel Howell wants to see you on the double."

I grabbed my calendar notebook and rushed out the door. On my way up the three flights of stairs I pulled the squadron scarf out of my left leg pocket and hung it around my neck. I took the hat that usually hung casually from my right leg pocket and placed it inside my notebook. By the time I left the stairwell I made sure each flight suit zipper was closed and my neck zipper was even with the patches on my chest. Everything was in military order.

I entered the outer office and the secretary waved me right in. I walked in to about five paces from Colonel Howell's desk, saluted, and announced my presence. "Lieutenant Albright reporting as ordered, sir."

Colonel Howell pretended not to notice. He kept his eyes on his desk. While keeping my eyes caged at twelve o'clock and parallel to the horizon, I was able to examine the commander's desk. His normally messy desk was cleared of all clutter except for a yellow, lined pad of paper and a stack of military orders. My orders! The yellow pad? In big black print were the words "Not Members" with two bold underscores. Beneath that were five names, two crossed out. On the top of the list was my name.

Finally he looked up at me and returned my salute. "Why aren't you a member?"

How does that rule go? Not every battle is worth fighting, sometimes you get further if you accept a few setback along the way. "I am joining today, sir."

"Fine," he said while taking a pen from his sleeve pocket. He signed my orders and handed them to me.

Leaving the alert facility pad for the last time! My final Strategic Air Command responsibilities behind me, I drove my 1972 Camaro over the snow packed road to the T-37 hangar. The sky was crystal clear but we still had several feet of snow on the ground. Since I was coming off alert Russ would have the airplane preflighted and ready. All I had to do was pull my parachute, oxygen mask, and helmet off their pegs. Russ was seated in the airplane already, waiting. I hopped in the jet and we were off.

Russ flew us to Pease while I made all the radio calls from the right seat. He flew the aircraft smoothly and precisely, matching all my preconceived notions. He was a good guy, a good friend, so he was destined to be a good pilot. We traded touch and go landings until we reached bingo fuel, and then did our full stop landing. Nearly three hundred gallons and twenty minutes later and we were on our way to Virginia, with me in the left seat this time.

A couple hundred miles south of the snow, we repeated the fly, touch-and-go, refuel routine at Langley Air Force Base. After a quick and late lunch we traded seats and headed north again.

The T-37 was the Air Force's primary jet trainer made in the fifties in enough numbers to crank out a couple of thousand pilots a year. That was when it took a lot of aircraft to fly all the cargo and drop all the bombs needed for an Air Force that consumed pilots. Pilots died in training, pilots died in war, and pilot's fled in record numbers for the airlines. Now, decades later, the Air Force no longer tolerated a training accident every week, the Vietnam war no longer digested pilots by the score, and the number of aircraft was only a fraction of what it used to be. One modern cargo aircraft could do the work of ten. One modern fighter could hit its target the first time instead of sending twenty fighters with less of a chance of seeing their bombs score a bulls eye. Fewer pilots leaving and fewer cockpits to fill meant a lot of T-37s with nothing to do. That's why they gave us copilots the keys to these jets and orders to fly.

It was a great way to learn quickly. No supervision, little guidance, and the orders to fly our butts off. It was also a great deal for the Air Force. We copilots grew up quickly and with less expense than the bigger, more modern aircraft we were destined to take command of in the future. The few of us who killed ourselves didn't take a big, expensive airplane with us. The T-37 was expendable.

I flew the T-37 more than I flew the tanker. But I was always exhausted. Spending a good portion of my life at 25,000 feet in an unpressurized airplane was taking its toll. My ears were always popping long after these flights after many hours of breathing pure oxygen. My joints always ached from the nitrogen in my blood stream coming out of solution on each ascent. But most of all, I needed more sleep.

Sleep was what many of us often did in the right seat of the T-37. But not me, I was above that kind of laziness. That is, I was too good for that until tonight. I was dead to the world about eight p.m. in the dead of winter descending into Rochester, New York with Captain Russ Rider at the controls. I remember the weather was supposed to be pretty crummy, light-to-moderate snow with low ceilings and about a half a mile of visibility. It was no time to sleep.

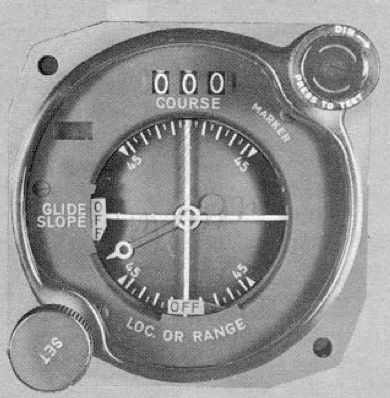

Before we continue our saga here, we need to make note of two finer points about the Cessna T-37 "Tweet." First, the T-37 is a flying tank. It can take a beating and keep on flying right until it flies into the side of a mountain. It has a huge straight wing that can take a lot of G's flying loops and spins as well as a ton of ice flying into weather it shouldn't be in. Second, the T-37 has what pilots used to call a "shot gun cockpit." They fired a shotgun at a clean piece of sheet metal and wherever they found a hole, they put in an instrument. And these were the cheapest instruments they could find. Unlike modern instruments, the T-37's course indicator didn't necessarily always point up and the course it was indicating didn't always move on the side the course was. You could be looking at a course pointing behind you and to the left and a deviation indicator to the right but really be aimed right with the course left. It wasn't rocket science, but it took a few seconds of neuron firing to understand what your eyes were telling you. And that's where I found myself that night.

The drone of the engines, the pure oxygen, and the fourteen hours since my alert facility pillow put me right to sleep. The dream that came was interrupted only when the volume and pitch of the sound of the engines dropped suddenly. I opened my eyes and saw nothing but a white sheet of ice on the canopy windscreen. Looking right I could see maybe an inch of the stuff coating the leading edge of the wing. The sight to the left was even scarier. Russ was glued, motionless, to the instruments but the instruments were screaming at him. The course indicator was ninety degrees off our heading, or more accurately, we were heading ninety degrees away from our course. The course deviation indicator was fully deflected. The altimeter was at 800 feet and unwinding itself at 700 feet per minute. In other words, we would be dead in less than a minute.

"Go around," I said, "Go around now."

"Why?"

"Just do it or I'll do it for you."

Russ did as instructed. As the engines roared to life and he pitched the nose upward, I began a series of the biggest lies of my life. "Rochester approach, Ace Five Three Two missed approach, has lost all navigation equipment and is requesting no gyro vectors to Plattsburgh."

"We haven't lost our nav equipment," Russ protested.

"I'll explain later," I said, pulling the charts for Plattsburgh. "Speed up as fast as you can get her and maybe some of that ice on the windscreen will sublimate." I managed to smile inside my oxygen mask; it was a ridiculous thought. How can a T-37 pick up that much speed? But climbing above the cloud layer and the increased speed did something, Russ and I both gained about a dollar bill sized port through the sheet of ice. Russ flew a very nice ground controlled radar approach at Plattsburgh and landed us with just that small patch of window in front of him. As we taxied into the ramp the linesmen gathered around the airplane pointing at the wings, the tail, and our windscreen. There was ice everywhere.

Before the engines had reached zero percent Russ said, "Now what was all that about?"

"Russ, I fell asleep. When I woke up we were less than five hundred feet off the ground with the airplane covered in ice, no forward visibility. We were ninety degrees to course with full scale deflection."

I heard the unmistakable sound of someone vomiting in his oxygen mask. I got out of the airplane in record time and spent the next hour in the comfort of the base operations shack watching the ice fall off the wings while Russ cleaned the cockpit.

We flew home the next day in silence. I've never seen Russ since then. I heard he is a Delta Air captain now.