They say we are all products of those who came before us and I suppose that is more true of pilots than most. When it comes to leadership I like to say I've learned from the worst, but when it comes to aviation I would say I've learned from the entire range. That's where Dan Gallo comes in.

— James Albright

Updated:

2013-12-02

When I showed up in Hawaii the only fans of Gallo were those on his crew. They would do anything for Dan and wouldn't trade being on his crew for any other. The rest of the squadron hated him and there were metaphoric Gallo voodoo dolls hidden everywhere. "Gallo Sucks" was written in just about every bathroom stall on base.

I ended up on Dan's crew and true to form, I ended up a Gallo fan. I owe to Dan my entire philosophy of crew pre- and post-briefs, crew integrity, and situational awareness. You can learn a lot about these subjects here:

The Interview

For a first lieutenant whose entire flight experience thus far involved parachutes and oxygen masks, the EC-135J was quite the machine. A military version of the Boeing 707, it had the same basic shape as the KC-135 tanker that I was flying, but a larger wing, bigger engines, lots of seats, and lots of radio gear. The cockpit was filled with stuff I didn't recognize and the airplane was beautiful.

The interview included a flight in the jump seat to see what refueling looked like from the receiver end and to spend some quality time with a couple of squadron pilots. That's when I first met Dan Gallo, the squadron's chief of standardization.

Major Gallo taxied the aircraft from the left seat while copilot Chris read from the checklist and negotiated with Honolulu Ground Control to get us into the line of airliners waiting for their turn on the reef runway. "Takeoff briefing," Chris said over the interphone, holding his finger on the appropriate line in the checklist.

Dan spouted off the noise abatement procedures for the airport, which involved an immediate right turn at half bank then full bank at the minimum altitude allowed by the airplane's flight manual. He covered the five immediate action emergency procedures and ended with "all members of the flight deck are responsible for traffic clearing procedures," and looking at me over his right shoulder, "that includes you, lieutenant."

I nodded from the jump seat and Gallo turned his attention to pulling up behind the next aircraft, waiting our turn for takeoff from the reef runway. Finally we got our clearance. Chris called out each item on his checklist until it was complete, placed the checklist on the floor between his seat and the center console, and placed his left hand behind the throttles and his right on the yoke. Gallo pushed the four throttles forward and Chris fine tuned them from below. At decision speed Dan removed his right hand completely. At rotation speed Dan pulled back on the yoke, called "gear up," and banked gently to the right. I looked over Dan's left shoulder to see Keehi Lagoon disappear behind us.

A few seconds later Dan called "flaps up" and steepened his bank. Chris moved the flap handle up and reached to his left for his plastic-bound checklist. Dan, still flying the airplane with his left hand, reached over with his right and grabbed the checklist from Chris. With a flick of his wrist he threw the checklist backwards. I ducked just in time and heard the booklet whoosh over my head. I turned around and saw that with the deck angle of the aircraft helping, the checklist ended up almost halfway down the aircraft aisle, a throw of a good fifty or sixty feet.

"Your eyes," Gallo barked, "belong outside right now." I sat upright and made sure I too had my eyes glued outside.

After the flight, Major Gallo debriefed his crew and filled the room with cigarette smoke. I did my best to restrain a cough and listened quietly. His critique points were very good and it was one of the best debriefs I had ever heard. Still, none of that made up for the flying checklist. Chris and I left the office and he let me in on a squadron saying I would hear many times in the years to come: "Gallo sucks."

The First Training Sortie

One year later, I was in the right seat of the same aircraft with Major Gallo in the left seat. It was my third training sortie in the EC-135J and my first with Gallo since that interview flight and the flying checklist. I managed to keep my eyes outside the aircraft whenever we were in high density traffic and accomplished the checklist items from memory.

We were at Barbers Point Naval Air Station, flying touch and go landings on the short runway. As soon as we landed the aircraft we had to advance the throttles halfway, reset the flaps, reset the trim, and further advance the throttles once they had stabilized. "Stand them up, push them up, rotate" was the call. It was the fastest, most intense, most insane touch and go pattern I had ever seen.

After my first landing, Gallo was complimentary but suggested I was moving the flight controls with too much force and less was more when it came to flying this aircraft. I didn't know what he was talking about.

"You just sit there with your hands on your lap this time around the pattern," he said while gently adjusting the throttles with his right hand still holding a lit cigarette. He talked calmly about the pattern, the visual cues, and the need to balance aircraft energy by using the additional drag of flaps and landing gear to control the vertical vector of the aircraft without power changes. We had gone from 1,500 feet and 200 knots on downwind to aligned with the runway, fully configured, and right on approach speed. I took mental notes of the entire process, but wondered to myself how long that cigarette would remain lit. At 300 feet, Major Gallo snuffed the cigarette out, turned the "No Smoking" light on, and landed the aircraft. He accomplished the "stand them up, push them up" process on his own and sixty seconds later we were climbing back to pattern altitude and he had another cigarette burning between his lips. His aircraft energy balancing act has been a standard of mine ever since, minus the cigarette.

Major Gallo gave me several check rides over the next year and each was difficult but each was followed with a precise and insightful debrief. The worst part of each check ride was having to breathe his second-hand smoke but the techniques and pointers usually made it a fair trade.

A year later, Major Gallo hired me for his crew, adding "stan/eval" to my resume for the second time. Dan's office name was "Guido Bear," a homage to his Italian heritage I was told. The navigator was "Gonzo Bear," something to do with his rather large nose. The engineer was "Gordo Bear," I take it from his ample girth. I was tasked with coming up with my own Bear name, but chose to ignore the assignment. Nobody seemed to notice. The only addition to my normal flight routine was now the mandatory debrief, which usually included a flask of rum. Guido, Gonzo, and Gordo allowed me to pass on the rum and crack open a beer instead. On the road, every meal included a bottle or two of an Italian red wine. I've been addicted to Chianti ever since. But I had to add the smell of rum to the stench of nicotine as the price to pay for being a member of Crew One.

My duties now included maintaining the squadron's aircraft technical orders — the flight manuals — and administering written tests to squadron pilots. The testing program involved taking a book of questions and producing four different tests which had to be changed every six months. My predecessor solved the problem with an X-Acto knife, rubber cement, and a Xerox machine. That's the way everyone did it back then.

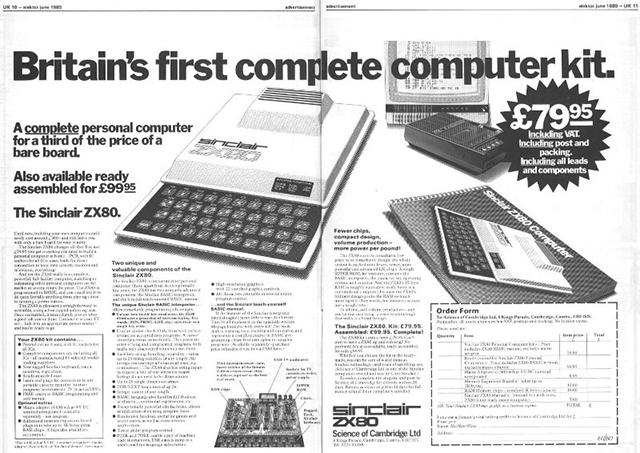

I did my semi-annual cut and paste in a day and found myself with very little to do besides fly. At first I dedicated myself to going to the beach three times a week, but after a month of this my next pay check brought out the guilt. I spent the next month trying to broaden my horizons at the base library when a British science journal gave me the motivation I needed. An advertisement from a company in Cambridge promised to bring me into the computer age for less than a hundred dollars.

I sent a check to Science of Cambridge, Ltd, and in less than a month had a bundle of parts and a single circuit board. Two weeks later I had a computer with a plastic membrane keyboard, no screen, and no storage device. It was great. With a bit of tinkering, I had the Sinclair ZX-80 hooked up to a television. After a lot of tinkering with an old typewriter and some paper clips, I had a real keyboard. After a visit to the local Radio Shack, I had a way to store programs on a cassette tape. I was in business.

My first program automated the copilot's chore of computing aircraft takeoff data. The other pilots in the squadron thought I was nuts. Major Gallo thought it was neat and asked me to build him his own computer. Of course I did so. For his machine, I put together a Plexiglas case and some additional memory: 2K.

My next program was the MQF, the Master Question File. It automatically produced stan/eval tests for our pilots which were randomly generated. We now had the best test producing system in the Air Force and our office won an award during our annual inspection. I called the rest of the office to attention and with great pomp and ceremony, tossed the X-Acto knife into the trash. Dan — he now insisted I call him Dan — Dan dubbed me "Ginzu Bear."

The best lessons

During one of my first few months on Crew One, we flew from Hawaii to Sacramento and ended up in Dan's hotel room for our mandatory debrief. It was Dan's leg and he critiqued his performance as mercilessly as he would mine. Each flight crewmember got a chance to chip in and it all ended with the ceremonial opening of the flasks for them, a can of beer for me.

One flask led to another and pretty soon I had downed an entire six pack, a lot for me. It was 3 am and I was beat. "Guys I'm going to have to get some sleep," I said while getting up to punctuate my resolve, "give me a call about noon if you need me, but I think I'll be skipping breakfast."

The three laughed at once, "show time is at seven, pup." They were right. Here we were drinking within eight hours of the flight and without the required rest period. I rushed to my room, got my clothes ready for the next day, set two alarms, and collapsed into my hotel bed. Three hours later I was up.

While the navigator and engineer looked a bit haggard, Gallo looked as fresh as ever. Things went smoothly during the preflight and all was in order for our passengers at the scheduled departure time. It was to be my takeoff which meant Dan would say "you have the aircraft" at 100 knots and I would assume control from that point on.

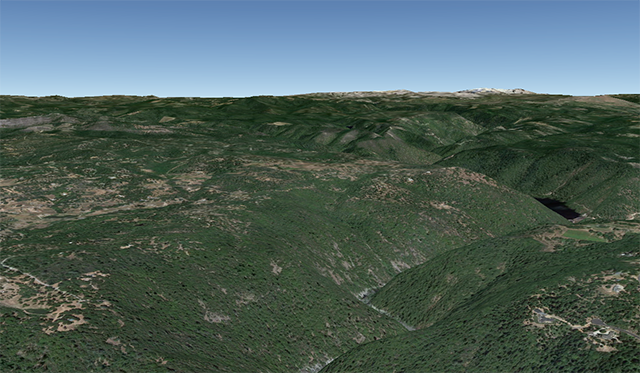

Dan taxied the aircraft onto the runway, pointed north, and pushed the throttles forward. At 100 knots I took control and when Dan called "Rotate" I hoisted the three-hundred thousand pound aircraft into the California sunlit valley. Once the altimeter and vertical velocity indicator both confirmed we were climbing, I called "Gear Up" and Dan raised the landing gear handle.

At 1,000 ft MSL — the altitude above mean sea level — Dan said "push the nose over."

"What?"

"Push the nose over."

I did as instructed. We normally pushed the nose over at 1,000 ft AGL — the altitude above ground level — to accelerate the aircraft and retract the flaps. At 1,000 ft MSL we were barely 300 feet above the ground. I kept my eye on the terrain as I accelerated, retracted the flaps, and finally put some distance between us and the dirt.

Once at cruise altitude I engaged the autopilot, finished my checklist chores, and asked Dan the question I had been pondering for the previous 33,000 feet. "So was that a new technique, cleaning up at three-hundred feet?"

"What are you talking about, we were at a thousand feet."

"We were at a thousand MSL."

Dan's face betrayed his thoughts, he was stunned. He sat silently for a while. That evening, at our debrief, Dan covered the takeoff in minute detail and admitted his hang over induced mistake. From now on, he declared, the eight hour bottle-to-throttle rule was to be obeyed, without exception.

Dan's Last Flight

A year later, we were in the traffic pattern at Barbers Point with a third squadron pilot when Dan announced it was time to let the navigator try one. The third pilot climbed out of the copilot seat and Gonzo Bear hopped in. Our navigator was a civilian pilot and it would seem knew how to fly our Boeing just fine. His touch and go wasn't the finest I had ever seen, but it was safe.

The next week I found out Guido Bear was fired. The third pilot turned him in, the squadron commander went ballistic, and Dan was gone.

A few years later Dan was hired by Midwest Airlines but never made it to the line. He was found dead in a hotel room the morning of his simulator check with the airline. The doctors said his kidney finally gave up and said, "to hell with it." So many cigarettes and so much rum. Dan was forty-four.

Everyone has a "What I Learned From Dan" Story

Twenty years later I was showing off my latest airplane to Chris, now a check airman for American Airlines. I was a check airman for a charter company and we traded stories about the strangest things we had ever seen while giving flight evaluations. Chris said he often used the flying checklist as an example to his pilots who spent too much time with their eyes inside the cockpit and not enough looking for the next potential midair. He spoke fondly of the lessons learned from Major Gallo.

Ever since our low level flight north of Sacramento I had been Dan's biggest supporter. His insistence on the open and frank debrief, his energy management techniques, and his willingness to admit mistakes made me one of his few supporters. Now it would seem he had another.

"Oh Gallo still sucks," Chris said, "but he was absolutely right about eyes out of the cockpit down low. That was a lesson I'll never forget."

Those are the best kind.