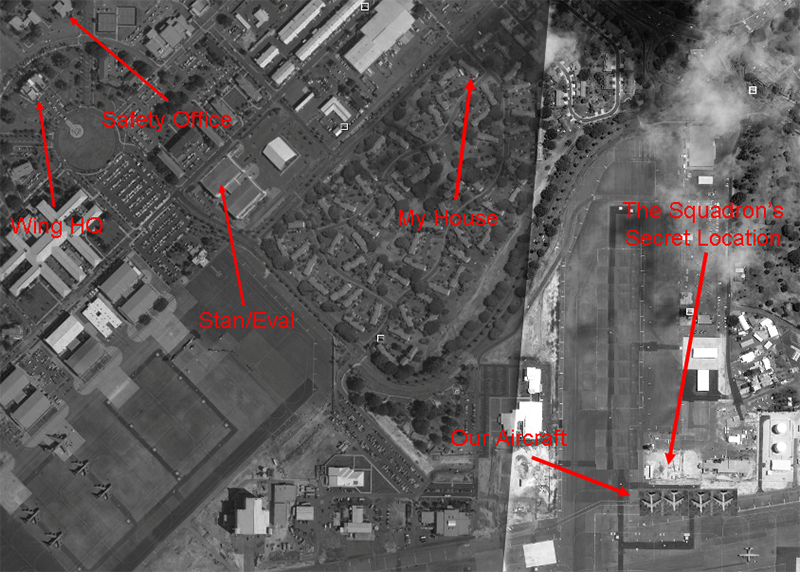

I was in my twenties living in Hawaii. I couldn’t afford a house on the outside, but the good folks at the Hickam Air Force Base Housing Office were kind enough to give me one right there on base. Our little piece of heaven was just 1 mile away from wing headquarters, the safety office, standardization & evaluation, and the squadron — the focal points of my five years there.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-02-01

The good thing about being the closest pilot to the squadron was I had the shortest drive home after a long trip. The bad thing about being the closest pilot to the squadron was that I was the closest pilot to the squadron.

It was my first week off in a while but vacation was officially over Saturday morning at 0700. I had no idea what trips were on the road, what I had on tap for the week to come, or what the status of our four birds was. But it was Saturday and if they wanted to call they could. They did.

“Capt,” the maintenance officer said from his office somewhere on base, “we have a squawk on one of your birds we haven’t been able to fix, and we’d like you to come in and taxi the airplane to help the troubleshooters."

It would be a five minute drive to the hangar, thirty minutes to preflight, and then however long they needed me for the taxi tests. It would be a few hours out of my Saturday. But any other pilot in the squadron would be driving in from off base and that meant at least another hour each way for them.

“I’ll be right in.”

I showed up on the flight line to a line of blue bread vans — so called because they looked just like the Wonder Bread trucks you see around the city every morning delivering freshly baked bread — surrounding the nose of the broken airplane in question.

“Thanks for coming in captain,” the line supervisor said, clipboard in one hand and unlit cigar in the other. “We have the aircraft buttoned up ready for engine start, Sergeant Devere hanging from the nose gear uplock in a cargo strap, Sergeant Wilson in the right seat to ride shot gun, and we have clearance from ground control for you to make a series of left turns around the ramp.”

“What?” I asked.

“Yeah captain,” the line super said, “the last couple of flights the crews said the nose gear was making a loud metallic clanking noise on all left turns. We’ve been up and down the nose well and checked out all the systems and we can’t find a thing.”

“No,” I said, “I understand that. Tell me again about Sergeant Devere.”

“Oh,” he said, smiling. “We figured the best way to troubleshoot this thing would be to hang a guy inside the nose wheel well while you taxi the jet. He’ll be able to figure out where the noise is coming from.”

I looked under the nose wheel well and there was Sergeant Devere, hanging from a cloth cargo strap draped over the nose wheel uplock lever. The uplock is about seven feet of the ground, just forward of the nose wheel in the extended position. The nose wheel itself is around two feet in diameter and behind that would be around 200,000 pounds of airplane.

“Howdy, captain,” he said, “I’m all set when you are.”

“This isn’t going to happen,” I said to nobody in particular, “it isn’t safe.”

“No problem,” the line supervisor said, “the chief of maintenance said it was a good plan and Danger Dave volunteered." Sergeant Dave Devere gave me a wide grin.

“I’m not doing it,” I said.

“Captain,” the line supervisor said with a hint of irritation, “you want the jet fixed? I want the jet fixed. Hell, even Danger Dave wants it fixed. Let’s get it fixed.”

“If that strap breaks or slips from the uplock,” I said, “I will end up running over Sergeant Danger up there. I’m not doing it.”

The chief of maintenance by this time had showed up, more line crew chiefs, and a host of weekend maintenance help all weighed in. The consensus of the maintenance side of the equation all agreed this was the way to go.

“Let me taxi the airplane with nobody in the wheel wells first,” I said. “If I can’t figure it out, I’ll think about the Danger Dave option.”

“We’ve already tried that,” the chief of maintenance said. He was a major and I was a captain. But I had the only valid driver’s license for the jet so I got my way.

I fired up all four engines, we closed the doors, and with a cockpit filled with mechanics, I drove up and down the Hickam Air Force Base ramp. With every left turn there was a definite “Ka-clank.”

“See!” the mechanics sung out, “every left turn. Just like that!”

I had never heard it before. I stopped the airplane to think. “Let me at it,” Danger Dave pleaded, “I know it’s coming from the nose strut, I just know it. All I need is a couple of minutes in the wheel well while you taxi just like that. The sound was coming from beneath me and to my left. I didn’t feel anything in my left hand, which controlled the nose wheel steering tiller. My feet were on the brakes, but there was no feedback there either.

“Just a minute,” I said to the mob, “hang on.” I taxied the airplane to an empty spot on the ramp, craned my head to the left so I could see the left wing and pulled the tiller hard left.

“Ka-clank!” I heard again as something flashed in the sunlight beneath my line of vision and inside the cockpit. I stopped the airplane and turned in my seat to set my eyes on the cause of the problem.

The cockpit of the EC-135J, our modified Boeing 707, is fairly generic and almost identical to those found at many airlines. To the outboard of each pilot was a large bin most airline pilots used to store a large catalog case of instrument charts. We tended to keep our DOD instrument charts on the right side and on the left we kept other forms and four metal plates, each about ten inches tall and a foot and a half wide. On each metal plate was one, two, three, or four stars. We would place the appropriate plate in the pilot’s left window to announce to the greeting party at the red carpet the horsepower of the military dignitary on board. The bin was usually a collection spot for magazines, comic books, or whatever the crew happened to leave there. I never used the bin except to retrieve or store the metal plates. For the first time in my experience the bins were devoid of the extraneous magazines and only had the metal plates with the stars.

I turned around in my seat to see the line supervisor standing. “Keep an eye on these plates,” I said, “I think I found your noise.” I released the brakes, built up some speed, and moved the tiller hard left.

“Ka-clank!”

“You gotta be kidding me!” the line super said. He reached down and retrieved the plates.

“Let’s try that again.”

I pulled the tiller again, hard left.

Silence.

I got home from the flight line and announced to the Lovely Mrs. that now, after a few hours delay, we could head for the beach.

“What did you do at the airplane today?” she asked.

“I saved a man’s life.”