Shuttling a peacekeeping team around the UFFR (Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics) can lead to some interesting situations. We were coming out of the war zone between present day Armenia and Azerbaijan, just northeast of Turkey. That story appears here: Cold War. The threat there was obvious. The threat we faced after leaving the war zone was a bit sneakier.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-00-00

This was one of those "peace keeping" missions you hear about now and then. We had an airplane full of senators and other diplomats who were trying to broker a peace deal between two of the satellite nations breaking apart from the Soviet Union. We were suitably trained and our flight plans had clearance from the State Department. What could possibly go wrong?

On course?

This was my first experience with meaconing. Well, not my first experience. I think it was my first experience where the safe outcome of the flight was in doubt. Yes, that's more like it. So what is meaconing? From the Department of Defense:

Meaconing is the interception and rebroadcast of navigation signals on the correct frequency at a higher power than the original signal to confuse enemy navigation.

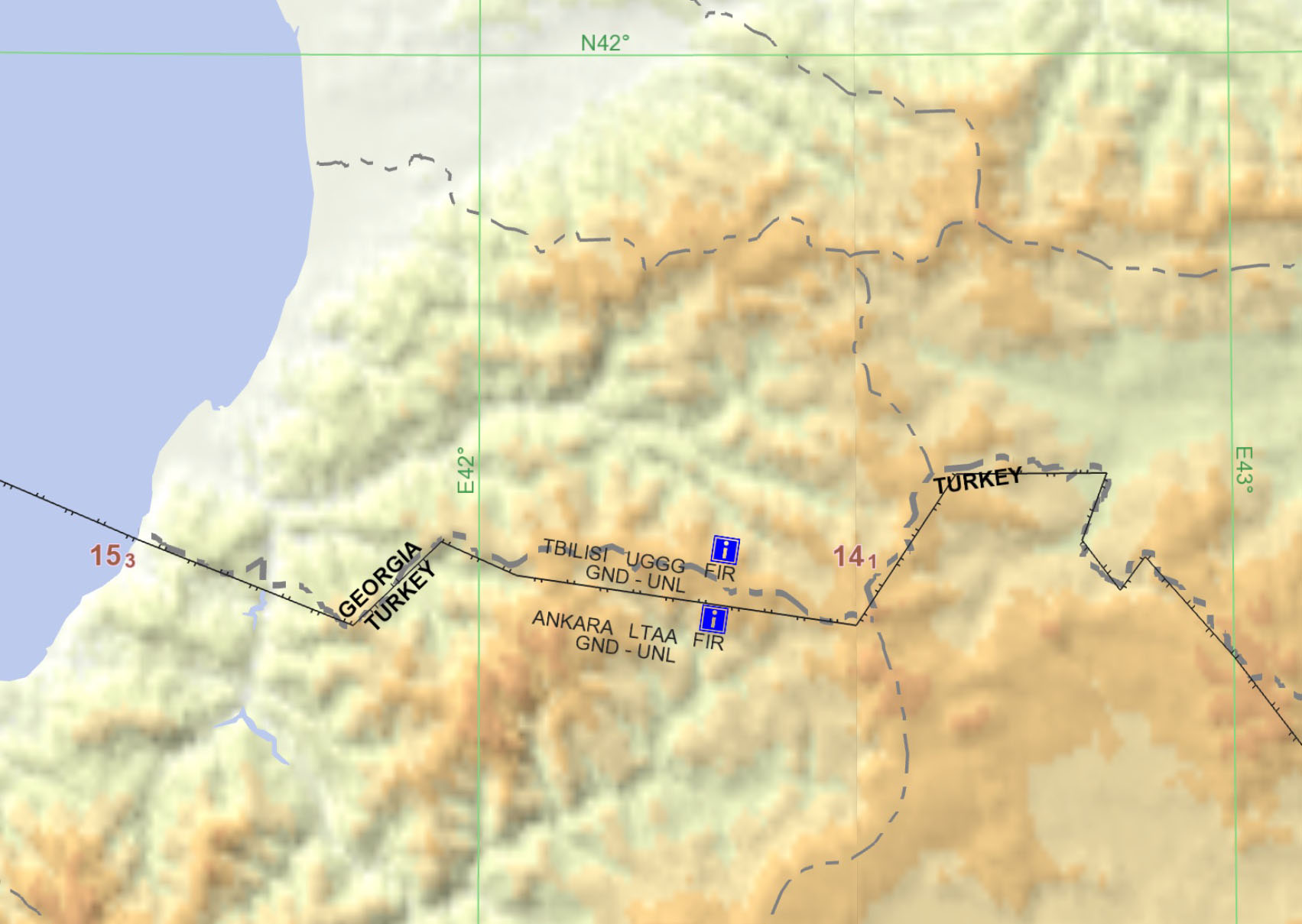

I was in command of a Special Air Missions flight from Armenia to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. We had a specific air corridor to fly, right down the center of Turkey, just north of a warning area which would have been called a "no fly zone" had the terminology existed back then. The jet route just north of the warning area was defined by two high power VOR stations and it should have been no problem staying out of trouble.

I was in the left seat of our C-20B, Gulfstream III, looking at a synthetic line drawn by our two Inertial Navigation Systems (INSs), which used a laser ring gyro to compute our position based on the coordinates we gave it prior to takeoff. The accuracy was nothing like today's GPS, but we could expect a drift of only a mile or two every hour. That was pretty good back then. I don't think I ever saw an error greater than 4 miles after seven hours of flight.

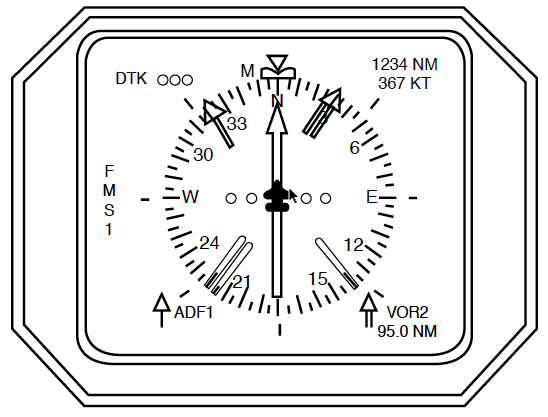

Mike was in the right seat. He was charged with dialing in each VOR to ensure the INS were doing their jobs. We flew all over the world like that when over land, and we expected to see both sides of the cockpit with centered needles. Mike was becoming unhappy.

"We are diverging from the course centerline," he said. "It looks like we need to turn south a good five degrees or so."

I looked over to his Electronic Horizontal Situation Indicator (EHSI) and confirmed he had the correct VOR and course. Everything was correct. Then I checked each INS. Both agreed with what I saw on my EHSI, casting doubt on Mike's. "I've never seen both INS go off course at the same time," I said. "Let's pull out the TPC."

We tended to fly with a stack of Tactical Pilotage Charts (TPCs) to cover our entire trip, especially when flying in war zones. The VORs were telling us to turn south. The INSs were saying we were just skirting a warning area. The instrument charts gave the typical warning for these areas, "aircraft may be fired upon."

Mike unfolded the chart and oriented it along our westerly heading. "That line of mountains over there," he pointed out the window. "That looks like this one here," he said pointing to the chart. It was a clear day and we had no problem coming up with our position on the chart, using our eyes and nothing else.

"We are on course," I said. "The VORs are lying to us. But why would they do that?" It didn't make any sense. We were in the middle of Turkey.

"Radio," I said over the interphone, "get me the Andrews intel shop."

"Pilot, button seven," the radio operator said after a few minutes of doing what radio operators do. I explained the situation to the intelligence officer back at our home base but they had no intelligence to share. "First we've heard of this," the sterile voice said. "We'll get back to you on this."

We decided to trust the INS, the TPC, and our eyes. The VOR needles swung further left, begging us to follow. We didn't. Three hours later we were on the ground at Incirlik.

Two weeks later I was back at Andrews Air Force Base, filling out a report with the intelligence office. I handed my report to a clerk and headed for the door.

"Major Albright," I heard just as the door started to close. I turned and propped it open. "You were the pilot on SAM 602 over Turkey?"

"I was," I said.

"Our boots on the ground confirmed it was meaconing," the captain said. "We didn't know it at the time, but we found out the next day that the Turks spun the VOR five degrees counterclockwise hoping to get you to follow it."

"Why would the do that?" I asked.

"They were against the peace agreement your passengers were brokering," he said. "It would have been a good pretext to launch a few missiles at you."

"The world has gone mad," I said.