Most of us captains have one thing in common: we all think we are good captains and that our crews agree. Nine out of ten benevolent dictators agree: “My people love me!” When the person in charge asks you for your opinion, your answer is probably preordained. “Yes captain, you are a good captain.”

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-07-10

I once went through an initial type rating training with a retired airline captain who seemed remarkably deaf when it came time to learn how a business jet crew operates. Though I had decades of experience flying Gulfstreams and he had zero, he wasn’t interested in my opinions after he made his decisions. Our instructor would make a comment about his Crew Resource Management (CRM) and he would get upset, saying he always got the highest marks from his airline crews about his CRM. Years later I met someone who flew with him, and his story was different. “He’s kind of a jerk. He was the captain, and I wasn’t. End of story.”

That was a couple of type ratings ago and I rarely give this captain much thought except when I catch myself being “kind of a jerk.” As an Air Force pilot, I was taught that you must be a jerk now and then when the mission takes precedence over people’s feelings and “you have to expect a few losses in a big operation.” As a civilian pilot, I try to minimize that kind of thing but still worry about it. Military or civilian, I’ve concluded that good aircraft captains have a few things in common: they are good pilots, they understand their job as captain, and they know how to command as leaders. If you fall short in any of these categories, you need to pick up your game if you ever hope to be a good captain. If you have these skills already, you need to work hard to maintain them.

1 — Better captains are better pilots

2 — Better captains understand their jobs as captains

1

Better captains are better pilots

The title “captain” confers upon pilots a certain level of respect and authority. There are captains who exist purely on that which comes with their assigned position. They passed the minimum level of testing and earned the minimum level of ratings so that they are “good enough.” This will only take them so far. Better captains must have the earned respect that only comes from a reputation or history of demonstrated competence as pilots. They might be extremely effective leaders and managers, but if they are lousy pilots, they are destined to be lousy captains.

In some of my Air Force squadrons and civilian flight departments we had pilots who were destined to be copilots for life and others who had upgraded to the left seat that had to be paired with very strong captains. These pilots, it was said, were “accidents waiting for a place to happen.” The fact that some of them became captains was an organizational mistake that only serves as lessons for us in the future.

A good case study of a captain waiting for his accident ended badly on May 15, 2017 at Teterboro Airport, New Jersey (KTEB). The captain of Learjet 35A N452DA had a history of substandard training performance. He required three additional simulator training sessions to earn his aircraft type rating for a variety of reasons, most notably an inability to fly a circling approach. Reading the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) transcripts of that flight provides a chilling example of a pilot who feared having to fly a particular maneuver and, in the end, died trying to attempt it.

If you have gaps in your abilities or fear certain maneuvers you are trained and authorized to do, you cannot be an effective captain. You need to concentrate on improving your pilot abilities before you can hope to be a better captain. While simulator training is expensive, there are vast online sources that are free. I was once at a friend’s house where a copy of the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) was tied to the bathroom door. He said there was more information in the AIM than he could ever know, but he was going to devote any extra reading time to learning it. There is some wisdom in that. If you don’t know the first things about the circle to land maneuver, for example, AIM can get you started.

Once you’ve upped your pilot game to “good,” you next need to aim for “better.” The second article in this series, “Being a Better Pilot,” can further your skills with three rules that will keep you out of trouble. There is more to being a pilot than just operating stick and rudder. But there is also more to being a captain than just wearing the four stripes on an epaulette.

2

Better captains understand their jobs as captains

Good airlines and very good flight departments may have established training programs that teach young first officers about becoming captains, beyond the mechanics of flying from the left seat. Unfortunately, many organizations assume first officers will have picked up what they need along the way and no formal training program is available.

With or without a training program, many captains seem to understand almost intuitively what is needed. They do a good job of setting the right tone with the crew, they know how to execute the tasks at hand, they know how to make decisions effectively, and they are good mentors for their crews. They “get it.” Over the years I’ve met a few captains who don’t get it at all and are not aware of what “it” is in the first place. With most of these captains, it is simply a matter of awareness.

Set the right tone.

This is especially important with large crews but also pays dividends for a crew of just two pilots. My first exposure to a large crew was in an Air Force Boeing 707 where we had two pilots, an engineer, a navigator, a flight attendant, three radio operators, and three crew chiefs. We once had a brand-new captain whom I will call Brad. Brad was just a year older than me and was a fellow copilot in the squadron since my arrival, a year before. At his first crew meeting before a five-day trip, he introduced himself by name and rank but added, “just call me Brad.” In the week to come several crewmembers came to me and asked for my opinion on various matters and went away figuring a decision had been made. The crew chiefs started making their own decisions and the flight engineer became the final arbiter of fuel loading. At the end of the trip nobody was happy, and Brad was left wondering why the trip had gone so poorly.

Things can start on the wrong foot even with a crew of two. There are more than a few examples in accident reports but one that is more blatant than others happened on October 19, 2004 by a crew of Corporate Airlines Flight 5966. The pilots descended below the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA) on a non-precision approach into Kirksville Regional Airport, Missouri (KIRK), killing themselves and 13 of 15 passengers. This is more than just another “duck under” crash, it is one where the pilots failed to take their roles as aviators seriously. The pilots failed to make required callouts, failed to arrest their descent rate and then descended below the MDA without the required visual cues, failed to go around when alerted to their sink rate by the Ground Proximity Warning System. One of the ironies of the accident was that less than 30 minutes before crashing, the captain said, “too many of these [expletive] take themselves way too serious, in this job.”

Execute the mission.

A common trait among failed captains is having a long list of ready excuses why a trip had gone sour, why someone had complained of a “minor” transgression, or why it seems he or she has been put on an informal “no fly” list by other crewmembers. The answer may be as simple as everyone wants to be part of a winning team, nobody wants to be associated with a loser. Captains who get the job done regularly develop good reputations, those who don’t get reputations of another sort. You can’t become a better captain until you unlock what it takes to get the job done safely without alienating company leadership, your peers, and your crews.

Make decisions.

The hallmark of a good professional pilot is one who can make decisive decisions after dispassionately weighing the factors, hearing out any opinions, and explaining the rationale. A failed pilot will skip all three steps and will delegate the decision to someone else, make a snap decision based on a whim, or make no decision at all. For extra credit in the failed pilot category, the pilot can reverse the decision several times. All of these hallmarks, good or bad, are even more critical when it comes to the captain.

How does one become a good decision maker? I find that preparation ahead of the decision is key. You can never know too much and studying everything you can about the airplane and the operation will pay dividends. Then once the decision-making opportunity avails itself, collect the facts, discuss with the crew as time permits, and then make the decision. What a lot of vacillators don’t understand is that every difficult decision made in the past make future decisions that much easier. It is a skill that builds on experience.

Mentor the crew.

A good captain understands the value of developing first officers into good captains and to helping all crewmembers to achieve their own professional goals. A reputation for mentoring the next generation attracts the next generation, and that feeds the reputation. A better captain also understands that the act of teaching others solidifies the lessons in oneself. We learn better by teaching.

I was once in a flight department of two highly experienced captains and one lesser experienced first officer. My fellow captain would complain of the first officer’s ineptitude and the first officer would complain about the captain’s unreasonable demands. As the boss, I believed both pilots were to blame but the captain was more at fault because he failed to set the right tone and mentor our fledgling pilot. He said teaching was not part of his job description. I said it was part of the job for every captain.

3

Better captains know how to command as leaders

Most of our training as captains comes from our time as crewmembers watching captains in action. The effectiveness of that training depends greatly on the effectiveness of the captains we observe. Ideally, we will serve an apprenticeship with both good and bad. If you learn only from good captains, you may assume your captaincies will be easy and you will be ill prepared for the challenges to come. If you learn only from bad captains, you are at risk of what I call “the tormented become the tormentors” syndrome. The problem boils down to a question of authority. Some captains assume the authority bestowed by the rank of captain has no limits and is the answer to all disputes. Other captains believe in a pure democracy and that no decisions are above a crew vote. Clearly there is a balance needed.

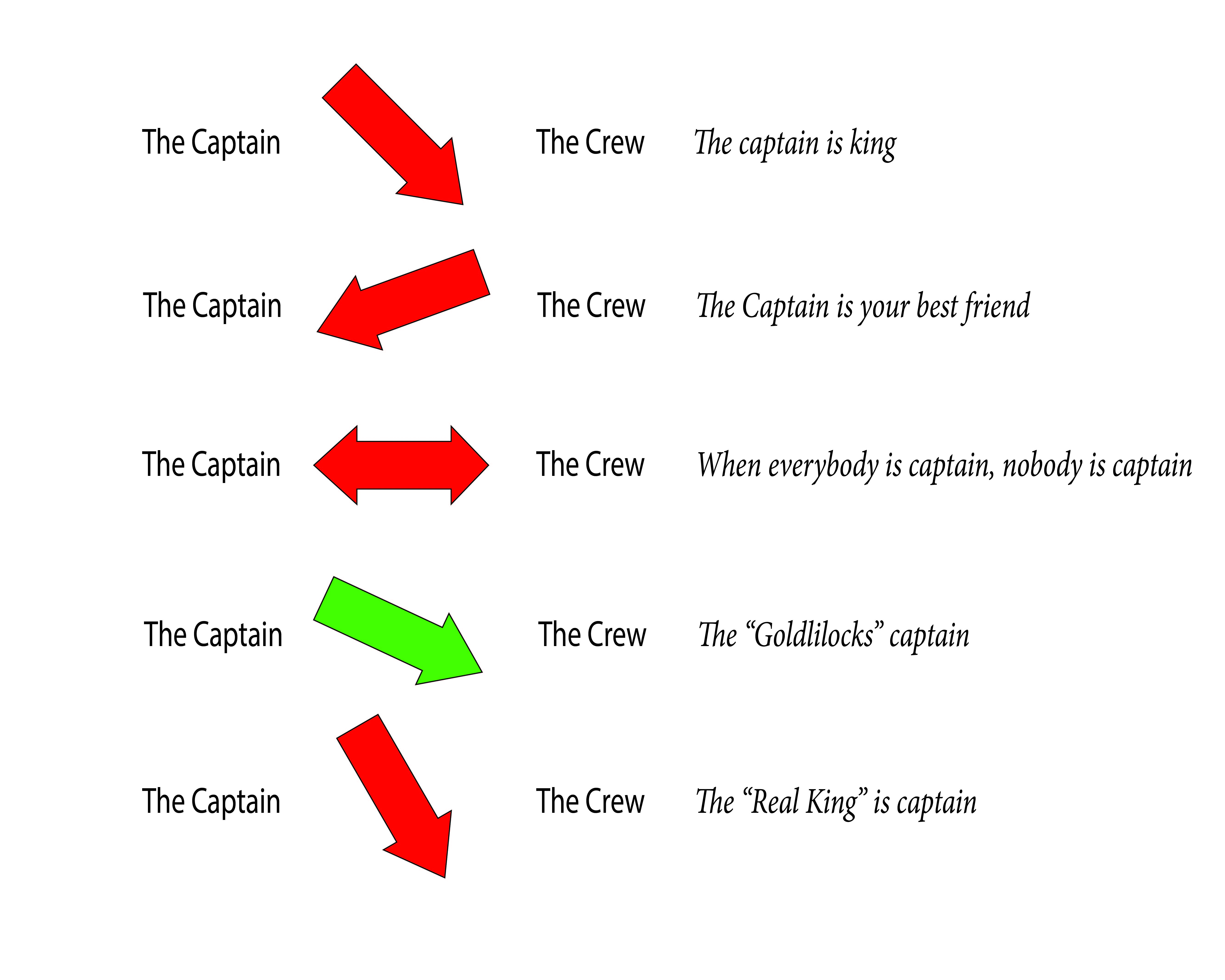

A trendy topic among human factors scientists is “Trans-cockpit Authority Gradient,” or TAG. The idea is that the captain has an authority that comes from sources beyond the title. It can be perceived from the captain’s age, experience, proficiency, confidence, physical size, assertiveness, or any other factor we can think of as “gravitas.” We are told that this authority gradient can be too steep, flat, reversed, or optimal. I think once again the scientists have made something simple too complicated.

A common model before the days of CRM is what the human factors gurus call a steep authority gradient; I call it the “captain is king” gradient. You will still find this at airlines with large seniority gaps and pilots who are hyper aware of their line numbers. While strong unions can protect first officers from tyrannical captains, there remains the thought that a bad review from one captain can spread to the chief pilot and other captains. Smaller flight departments can be at even greater risk, where the captains may have leadership positions that can determine a pilot’s pay, bonus, or even continued employment.

On the opposite end of the scale is the reversed authority gradient, where the captain cedes all authority. I call this the “captain is your best friend” gradient. While you can find best friend captains in any environment, small flight departments are at greatest risk. If the small crew force has been in place for a while, captains may be reluctant to exercise any authority that can be unpopular. A decision to divert, for example, can be overcome by the desire to get the first officer home for a child’s little league baseball game.

Somewhere in the middle of the king and the best friend is the flat authority gradient; I call this the “when everybody is a captain, nobody is a captain” gradient. If a captain has a reputation for always ceding a decision to the crew, when the time comes the captain does want the authority for a particular situation the crew may not give the authority back.

I think it is obvious to most effective captains that the correct authority gradient, the “Goldlilocks gradient” is with the captain exerting final authority but still inviting crew input, considering crew inputs when offered, and explaining decisions that overrule the crew’s wishes. What is less obvious and rarely discussed is what happens when the captain’s organizational boss or a charismatic, informal leader is a part of the crew. The “real king is here” gradient can be the worst kind of gradient if the real boss fails to actively encourage the captain to act as a captain. I found myself in this position many times and have learned from experience it takes an active effort to prevent this gradient. Consider two pilots getting an aircraft ready for the day’s trip. The first officer is the flight department’s director of aviation and the one who turns in an end of year evaluation and recommends pay raises and bonuses. The other pilot is a fully qualified and properly designated captain for the trip, but also works for the first officer. If the mechanic approaches the first officer for direction on a maintenance deferral and the first officer / director of aviation decides, the captain’s authority is compromised and the tone of the trip is set off in the wrong direction.

The answer to all these gradient problems is simple. Everyone has a role to play and when everyone plays their role, life becomes predictable, simple, and safe. The key role, the starring role, is played by the captain.

4

So far, up next

In this series about being better, we have discussed how to be a Better Student, a Pilot, a Crewmember, and now a better captain. Each skill lends itself to all crew positions, especially the captain’s. A non-aviator may look at these suggestions and argue they apply equally well to all professions requiring a high level of skill and teamwork. And that is true. It all combines into the next and final article in this series: Being Better.