This was a poorly qualified crew, flying for an illegal charter operator, not understanding the critical nature of adhering to center of gravity limits on the Challenger 600 series aircraft.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-05-22

N370V Crash Site,

NTSB Report, Figure 1.

I flew a newer version of this airplane about ten years ago and during that period one was lost due to what the manufacturer claimed was a weight and balance problem but ended up being an inept test pilot. But all who fly the Challenger series should understand that weight and balance is one of their challenges. The aircraft tends to be nose-heavy and the heavier it is, the heavier the nose becomes, to the point of being out of limits.

There are lessons for us non-Challenger pilots as well. We need to understand the shape of our aircraft center of gravity envelope and what impact adding fuel, people, or things to various areas of the airplane have on the airplane's center of gravity. More about this: Weight and Balance.

1

Accident report

- Date: 02 Feb 2005

- Time: 07:18

- Type: Canadair CL-600-1A11 Challenger 600

- Operator: Platinum Jet Management

- Registration: N370V

- Fatalities:0 of 3 crew, 0 of 11 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Takeoff

- Airports: (Departure) Teterboro Airport, NJ (TEB) (TEB / KTEB), United States of America; (Destination) Chicago-Midway Airport, IL (MDW) (MDW / KMDW), United States of America

2

Narrative

On February 2, 2005, about 0718 eastern standard time, a Bombardier Challenger CL-600-1A11, N370V, ran off the departure end of runway 6 at Teterboro Airport (TEB), Teterboro, New Jersey, at a ground speed of about 110 knots; through an airport perimeter fence; across a six-lane highway (where it struck a vehicle); and into a parking lot before impacting a building. The two pilots were seriously injured, as were two occupants in the vehicle. The cabin aide, eight passengers, and one person in the building received minor injuries. The airplane was destroyed by impact forces and postimpact fire. The accident flight was an on-demand passenger charter flight from TEB to Chicago Midway Airport, Chicago, Illinois. The flight was subject to the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 135 and operated by Platinum Jet Management, LLC (PJM), Fort Lauderdale, Florida, under the auspices of a charter management agreement with Darby Aviation (Darby), Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which operated on an instrument flight rules flight plan.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, page ix.

3

Analysis

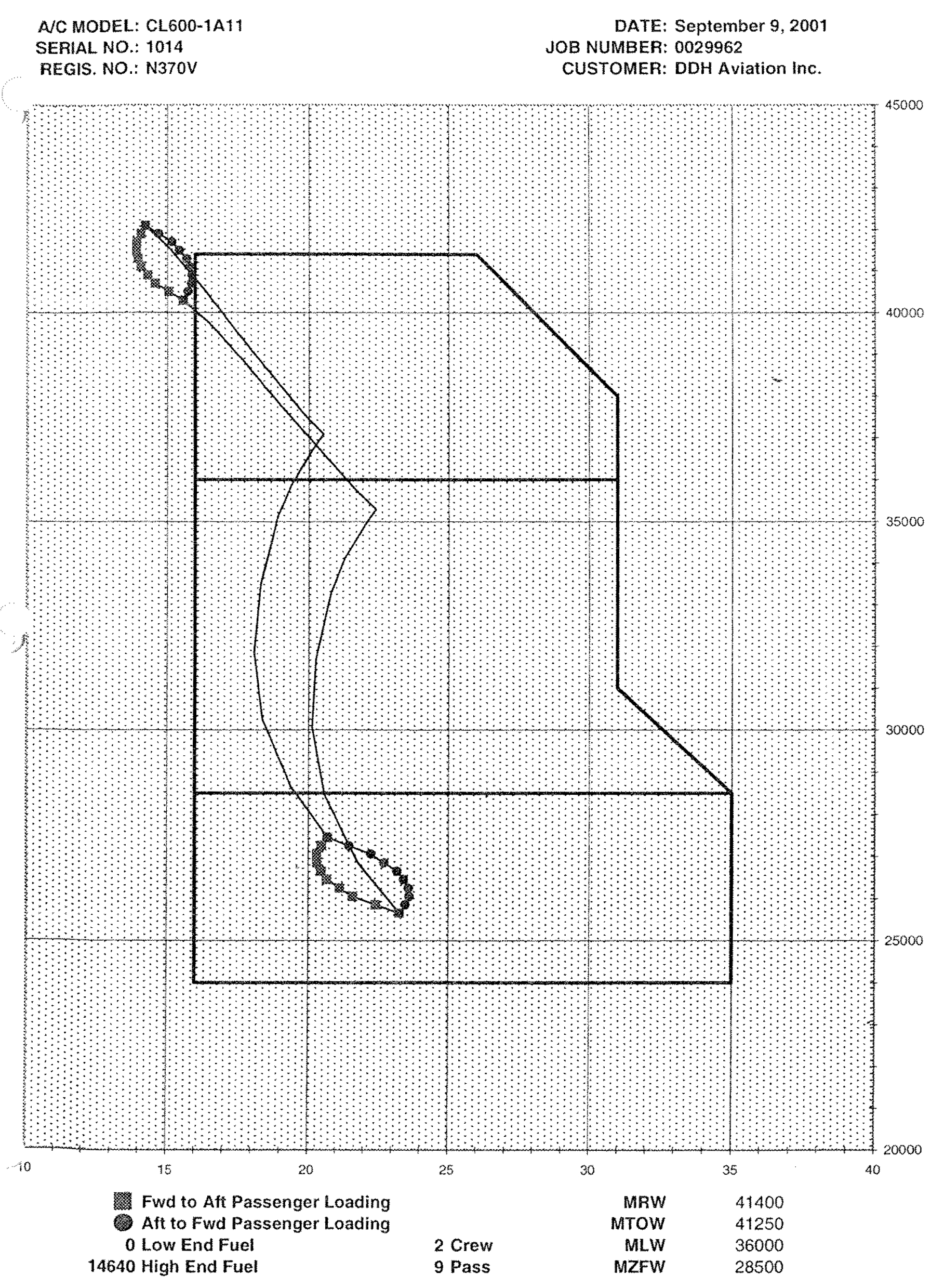

Challenger 600 Weight and Balance Envelope, from NTSB Accident Report 06/04, Appendix C, page 110.

During postaccident interviews, the captain and first officer told investigators that they did not perform manual balance calculations or use the airplane-specific weight and balance graph that was in the accident airplane.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶1.6.2.2.

Under 14 CFR 135.63 the crew was required to prepare a load manifest that includes the aircraft's center of gravity and the center of gravity limits. Even had they not been on a 135 leg, the FAA's usual response is to cite 14 CFR 91.7, "Civil Aircraft Airworthiness," which says the pilot-in-command of any civil aircraft is responsible for determining whether that aircraft is in condition for safe flight.

Neither pilot recalled calculating the airplane's CG before their attempted departure, and they stated that the only weight assessment calculated for the accident flight was performed using the flight management system (FMS) calculator. The FMS calculator totaled the passenger, fuel, and baggage weights based on input (or default) values; however, it did not calculate the balance information.

The Safety Board's examination of the weight and balance form that was completed for the inbound flight from LAS revealed that the airplane empty weight that was printed on the form had been modified by hand and that it was lower than the actual airplane empty weight. This lower airplane empty weight resulted in an incorrect (farther-aft-than-actual) empty weight CG. Further, the airplane empty weight that had previously been entered into the FMS (24,500 pounds) was incorrect (also lower than the airplane's actual empty weight). The airplane's empty weight was listed correctly (based on the September 2001 weighing) in the airplane flight manual (AFM).

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶1.6.2.2.

Both pilots recalled that the total fuel weight after refueling was about 13,900 pounds (the captain estimated from 13,800 to 13,900 pounds). However, a copy of the pilots' FBO fuel receipt showed a handwritten notation reading, "top off."

Data downloaded from the airplane's navigational computer unit indicated that a departure fuel weight of 14,600 pounds was entered into the control display unit on the first officer's side of the cockpit before the accident flight.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶1.6.2.4

The weight and balance chart for this airplane shows the effect of adding fuel toward the top of the range moves the center of gravity forward and can move it out of limits.

During postaccident interviews, the captain was asked to perform manual weight and balance calculations for the accident flight. The captain acknowledged that his postaccident calculations showed that, after the airplane was fueled, its weight exceeded its maximum allowable limit, and the forward CG exceeded the forward limit. However, he stated that the operation of the auxiliary power unit (APU) and engines during ramp and taxi operations would have consumed sufficient fuel to bring the weight and CG back within limits before takeoff. He stated that they took no actions to reduce the airplane's fuel load before takeoff.

Airplane, APU, and engine performance information provided by the manufacturers indicated that the CL-600 APU and engine operation described by the captain could have resulted in sufficient fuel burn to reduce the airplane's weight to its maximum allowable takeoff weight. However, the fuel consumed by the engines and APU during taxi operation would have come from the main fuel tanks located in the wings and would have resulted in the CG moving farther forward, thus further exceeding the forward CG limit.

The Safety Board's postaccident calculations (based on the completed weight and balance form for the airplane's inbound leg and documentation regarding fuel and other preflight servicing; postaccident information regarding passenger, crew, and baggage weights; and other airplane data and performance information) indicated that the airplane might have been about 100 pounds over its maximum takeoff weight and that its CG exceeded the forward balance limits by 3.53 percent MAC, about 20 percent of the entire allowable CG envelope at takeoff.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶1.6.2.4

Using the Safety Board's calculated weight and balance for the accident flight, investigators reconstructed the attempted takeoff in a full-motion simulator and reviewed multiple possible scenarios. The results from the simulator sessions and the Board's airplane performance study indicated that, under the accident airplane's loading conditions and configuration, the airplane would likely not have achieved nose-up rotation, even with full aft control column input, until after it accelerated past about 160 knots, well in excess of normal takeoff decision or rotation speeds.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶2.3.2

This captain had over 3,000 hours in type and should have known the aircraft was prone to a forward center of gravity that could preclude flight.

The Safety Board concludes that the captain's decision to initiate the RTO was reasonable, even though the airplane had already reached a higher-than-normal RTO speed.

The Safety Board also evaluated the captain's performance during the RTO by observing numerous RTO runs in a CL-600 simulator configured to match the performance of the accident airplane. In all cases, the simulator left the runway at a slower speed than the accident airplane. These excursions would likely have resulted in a variety of airplane stopping points at the airport perimeter, the six-lane highway, or the building impacted by the accident airplane. The deceleration levels observed in the simulator study indicated that throughout the RTO the accident pilot was not using the full capability of the airplane to stop and that the speed at which he exited the runway could have been significantly lower. It is imperative that once pilots make the decision to reject the takeoff, they immediately use all available stopping devices.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶2.3.2

The report notes the simulator pilots had the advantage of knowing they had to abort and does not list the captain's abort procedures in its findings. Pilots should, I think, practice maximum effort aborts in the simulator to learn a few things we took to heart in the Boeing 747: (1) a maximum effort abort requires you mash both brake pedals to the floor and keep them there in an airplane with an anti-skid braking system, (2) All other stopping devices (reversers, spoilers, etc.) need to be activated simultaneously, and (3) The abort isn't over until the aircraft has stopped and you don't release brake pressure until then.

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew’s failure to ensure the airplane was loaded within weight and balance limits and their attempt to take off with the center of gravity well forward of the forward takeoff limit, which prevented the airplane from rotating at the intended rotation speed.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, page ix.

The airplane, as loaded for the accident flight, had a forward center of gravity that was significantly forward of the airplane's forward limit, which severely degraded the airplane's ability to rotate.

Neither pilot used the available weight and balance information appropriately to determine the airplane's weight and balance characteristics for the accident flight and the pitch trim setting selected by the pilots is further evidence that they did not consider the airplane's center of gravity during preflight preparations.

The captain's decision to initiate the rejected takeoff (RTO) was reasonable, even though the airplane had already reached a higher-than-normal RTO speed.

The pilots' failure to ensure that the airplane's weight and center of gravity were within approved takeoff limits was symptomatic of poor airmanship and a broader pattern of deficiencies in their crew resource management skills (specifically in the areas of leadership, workload management, communications/briefings, and crew coordination) that were exhibited on the day of the accident.

Source: NTSB Accident Report 06/04, ¶3.1

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-06/04, Runway Overrun and Collision, Platinum Jet Management, LLC, Bombardier Challenger CL-600-1A11, N370V, Teterboro, New Jersey, February 2, 2005