The Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile (BEA) did a very nice bit of investigative work on this mishap with one exception: the conclusion wasn't forceful enough. Before I explain, let me dive into the very nature of aircraft mishap investigation.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-24

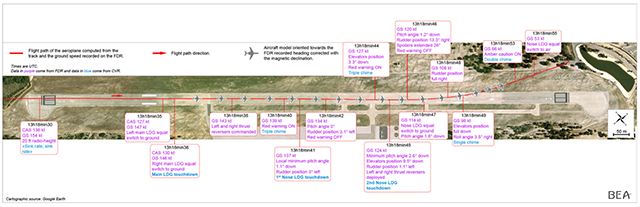

N823GA Ground Track,

from BEA Report, figure 2.

In theory, the primary motivation for investigating an aircraft crash is prevention. You don't want it to happen again. When I went to the Air Force Mishap Investigation Course and later to the Chief of Safety Course, we were told that our standard of proof was different than what the Judge Advocates General would use. They had to prove something beyond any reasonable doubt. In the safety business we don't have that restriction. Nobody was going to jail as a result of our findings, but somebody could be spared a future mishap. This report dances around the obvious because they don't have proof beyond all reasonable doubt.

My goal here is prevention. We can learn a few things from this mishap that can save lives. So let's do that. If I were writing this mishap report my findings, my personal opinions, would read as follows:

- The captain was a product of a long airline career flying with a major airline in sterile conditions where every operation was thoroughly pretested and validated to ensure it could be flown by the company's weakest pilots.

- The FAA failed to ensure the training vendor was doing its job when awarding type certificates.

- The training vendor failed to properly train the captain to operate as a pilot monitoring (PM) from the left seat and failed to fully cover known emergency procedures required in the aircraft's history.

- The operator failed to consider the captain's lack of experience in type and with corporate aviation.

- The operator and training vendor failed to enforce adequate checklist discipline.

- The operator failed to consider the lack of experience of the pilot pairing when scheduling them for a short de-positioning flight into a short runway.

- The captain had a track record of forgetting to arm the aircraft automatic ground spoiler system and was known to manipulate the controls (including the nose wheel steering) while flying as the PM.

- The pilot flying (PF) who was the Second-in-Command (SIC), failed to properly fly the airplane onto the runway, allowing it to float after main gear touchdown which allowed the thrust reverser system to arm but then disarm as the weight on wheels system switched from air to ground, to air again, before finally returning to the ground mode.

- The captain apparently had his hand on the nosewheel tiller and commanded a strong left turn to the nosewheel steering system. Once the nosewheel touched down, the aircraft started to veer strongly left.

- The captain was unaware of the proper procedure in this airplane to disarm the nosewheel steering system after such a deviation from a forward track.

Those are pretty harsh, I agree. But I hope it instills the following thoughts:

- You cannot hire highly experienced pilots thinking high total time and many years with one type of operation will translate to other operations. This captain was not suited for the responsibility as captain in a GIV or as a PM flying onto a short runway.

- A training vendor that is nothing more than a type rating mill is a recipe for bad things to happen. The vendor failed to teach the emergency procedure in question or the techniques needed to fly as a PM from the left seat.

- Checklist discipline is a life saver. Had the ground spoilers been armed the touchdown could have been more deliberate and much of the confusion that followed would have been avoided.

- You must fly the airplane onto the runway in an expeditious manner. An airplane is most vulnerable in the flare and any effort made to "grease" the touchdown can have other, unintended, consequences.

1

Accident report

- Date: 13 July 2012

- Time: 1318

- Type: Gulfstream GIV

- Operator: Universal Jet Aviation

- Registration: N823GA

- Fatalities: 3 of 3 crew, 0 of 0 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Damaged beyond repair

- Phase: Landing

- Departure Airport: Nice-Cote d'Azur Airport (LFMN), France

- Destination Airport: Le Castellet Airport (LFMQ), France

2

Narrative

During a visual approach to land on runway 13 at Le Castellet aerodrome, the crew omitted to arm the ground spoilers. During touchdown, the latter did not deploy. The crew applied a nose-down input which resulted, for a short period of less than one second, in unusually heavy loading of the nose gear. The aeroplane exited the runway to the left, hit some trees and caught fire.

The runway excursion was the result of an orientation to the left of the nose gear and the inability of the crew to recover from a situation for which it had not been trained. The investigation revealed inadequate pre-flight preparation, checklists that were not carried out fully and in an appropriate manner.

Source: BEA Report, pg. 8

- On Friday, 13 July 2012 the crew, consisting of a Captain and a copilot, took off at around 6 h 00 for a flight between Athens and Istanbul Sabiha Gokcen (Turkey). A cabin aid was also on board the aeroplane.

- The crew then made the journey between Istanbul and Nice with three passengers. After dropping them off in Nice, the aeroplane took off at 12 h 56 for a flight to Le Castellet aerodrome in order to park the airplane for several days, the parking area at Nice being full. The Captain, in the left seat, was Pilot Monitoring (PM). The copilot, in the right seat, was Pilot Flying (PF).

- Flights were operated according to US regulation 14 CFR Part 135 (special rules applicable for the operation of flights on demand).

- The flight leg was short and the cruise, carried out at FL160, lasted about 5 minutes.

- At the destination, the crew was cleared to perform a visual approach to runway 13. The autopilot and the auto-throttle were disengaged, the gear was down and the flaps in the landing position. The GND SPOILER UNARM message, indicating non-arming of the ground spoilers, was displayed on the EICAS and the associated single chime aural warning was triggered. This message remained displayed on the EICAS until the end of the flight since the crew forgot to arm the ground spoilers during the approach.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

This is a pretty easy thing to miss and will normally result in the airplane seeming to "float" when the main wheels touch. This is so because the ground spoilers normally come up as the wheels spin up or once the weight on wheel switches compress. If the ground spoilers are not armed, they will not automatically pop up. Because of this, many Gulfstream pilots become paranoid about this switch.

- At a height of 25 ft, while the aircraft was flying over the runway threshold slightly below the theoretical descent path, a SINK RATE warning was triggered. The PF corrected the flight path and the touchdown of the main landing gear took place 15 metres after the touchdown zone - that’s to say 365 metres from the threshold - and slightly left of the centre line of runway 13.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

That comes to 1,198 feet from the end of the runway, not bad. The runway is 5,069' long.

- The ground spoilers, not armed, did not automatically deploy. The crew braked and actuated the deployment of the thrust reversers, which did not deploy completely. The hydraulic pressure available at brake level slightly increased. The deceleration of the aeroplane was slow.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

If the main landing gear were firmly on the runway, pressing the brakes at this point would result in the nose coming down hard. The main gear were apparently not completely down and the aircraft's weight on wheels system was alternating between the "air mode" and the "ground mode," allowing the thrust reversers to arm and then disarm before finally re-arming.

- Four seconds after touchdown, a MASTER WARNING was triggered. A second MASTER WARNING was generated five seconds later.

- The nose landing gear touched down for the first time 785 metres beyond the threshold before the aeroplane’s pitch attitude increased again, causing a loss of contact of the nose gear with the ground.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

With the ground spoilers not deployed, the feel of the airplane after the flare is completely different. Depending on the pitch trim condition at touchdown, the nose could very likely have a tendency to pitch up. It took the pilot four seconds and nearly 1,400' to bring the nose down. At this point over half the runway was behind them.

- The aircraft crossed the runway centre line to the right, the crew correcting this by a slight input on the rudder pedals to the left. They applied a strong nose-down input and the nose gear touched down on the runway a second time, 1,050 metres beyond the threshold.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

A strong nose-down input may have been a response made in panic to the unusual pitch feel combined with the imperative of stopping the airplane on the runway remaining. (At this point they only had 1,625' remaining.)

- The speed brakes were then manually actuated by the crew with an input on the speed brake control, which then deployed the panels. Maximum thrust from the thrust reversers was reached one second later. The aircraft at this time was 655 metres from the runway end and its path began to curve to the left. In response to this deviation, the crew made a sharp input on the right rudder pedal, to the stop, and an input on the right brake, but failed to correct the trajectory. The aeroplane, skidding to the right, ran off the runway to the left 385 metres from the runway end at a ground speed of approximately 95 knots.

- It struck a runway edge light, the PAPI of runway 31, a metal fence then trees and caught fire instantly.

- An aerodrome firefighter responded quickly on site but did not succeed in bringing the fire under control.

- The occupants were unable to evacuate the aircraft.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.1

3

Analysis

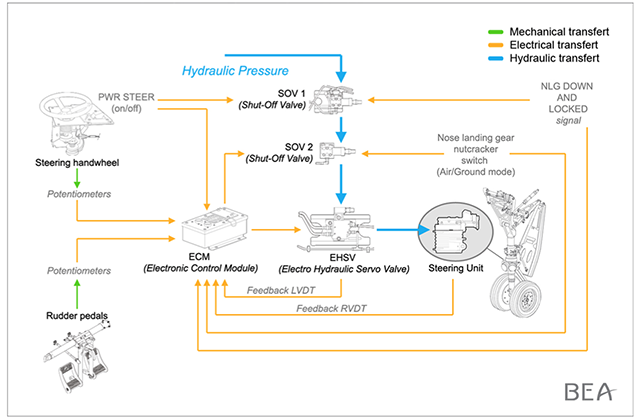

GIV Nose Gear Steering Control System, from BEA Report, figure 5.

- The nose gear steering system is electrically controlled, hydraulically operated and actuated by the crew. It is used during taxiing, take-off and landing. The orientation of the wheels is made via the steering unit which transmits the rotational forces via the torque links. The nose wheels are not braked.

- The crew can control the system using the tiller and a guarded ON / OFF "PWR STEER" switch on the left console. The control system consists of a tiller equipped with return springs returning it to neutral position, viscous dampers and potentiometers. The tiller is used to control the orientation of the nose gear up to 80° ± 2° to the left or right of the central axis of the aeroplane. The PWR STEER switch and the tiller are accessible only from the left seat.

- The crew can control the system through the rudder pedals. They are used to control the direction of the nose gear up to 7° ± 1° to the left or right.

- The positioning of the PWR STEER switch to OFF results in disconnecting the steering system. In this case, an input on the rudder pedals or the tiller has no effect on the direction of the nose gear.

- The activation of the steering system starts 250 ms after the compression of the nose gear is registered by the proximity sensor. Full activation of the system is effective 750 ms later.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.6.5

- At the time of the landing at 13 h 18, the maximum spot wind over a minute was 10 kt from 300°.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.7

(Basically all crosswind.)

The examination of the site and the wreckage showed:

- the aeroplane was in landing configuration. The thrust reversers were deployed symmetrically;

- the aeroplane was skidding to the right during the turn and the runway excursion;

- the aeroplane’s multiple impacts with the vegetation resulted in the wings breaking off and slowed down the aircraft;

- the rocks at the roadside were struck by the nose gear and the right main landing gear;

- the fuselage did not come into frontal contact with the trees and was not broken;

- the fire resulted from the rupture of the wings, which contained fuel;

- all of the doors and emergency exits were found closed and locked;

- the main landing gear wheels showed no signs of punctures or abnormal wear.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.11.1

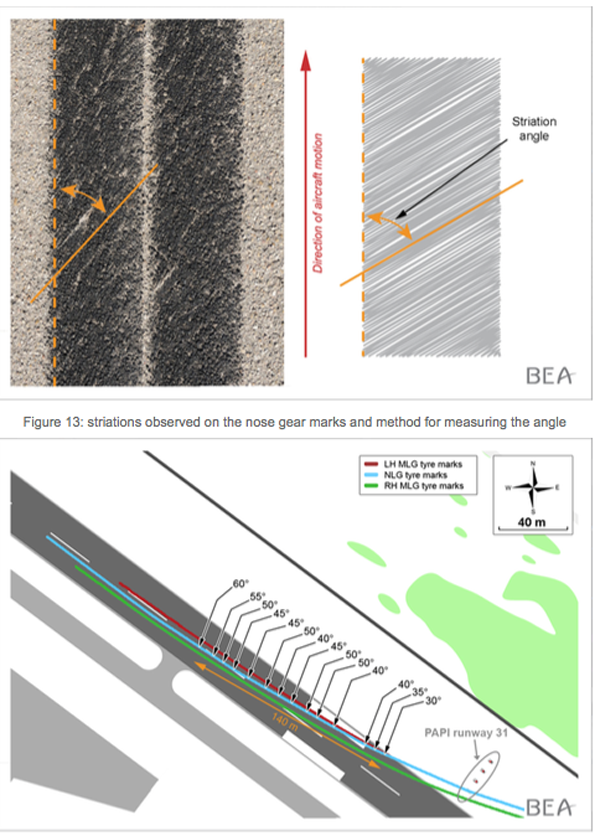

GIV Nose Gear Striation Values, from BEA Report, figure 14.

The first tyre marks observed on the runway attributed to N823GA were left by the nose gear. They were continuous to the runway edge over a longitudinal distance (in relation to the runway centre line) of 270 metres. Shortly before the runway centre line and until the runway edge these marks had striations trending towards the right in the direction of travel of the aeroplane. Their angle, measured between the edge of the mark and the striation, changed along the marks.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.12.2

If the nose gear is deflected to the left while the airplane is still headed mostly straight, the rubber tends to rub off to the right, the so-called striation marks.

- Examination of the tyre marks left by N823GA on the runway revealed the presence of rectilinear striations oriented to the right, in the direction of movement of the aeroplane.

- The study includes tests that show that, for an unbraked wheel, the striations are substantially oriented at 90° in relation to the plane of the wheel (parallel to its rotation axis). Their orientation is close to the direction of movement of the wheel if it is partially braked.

- This study shows that between the time of the second nose landing gear touchdown and the time of the runway excursion, the nose gear was strongly oriented to the left, generating marked marks and rectilinear striations.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.16.7

In order to study the dynamics of the aeroplane on the runway and the various possibilities that might explain the lateral deviation to the left and the runway excursion, Gulfstream, the NTSB and BEA independently carried out several simulations of the aeroplane’s trajectory.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.16.4

- The simulations carried out by Gulfstream failed to reproduce the trajectory of N823GA.

- The NTSB used TruckSim software to simulate and analyse the dynamic behaviour of heavy vehicles in contact with the ground. . . . The results obtained show that only an orientation to the left of the nose landing gear wheels could reproduce the N823GA’s trajectory.

- The BEA completed the model used for the calculation of vertical loads on the landing gear . . . only an orientation to the left of the wheels of the nose landing gear was capable of reproducing the N823GA’s trajectory using the vertical loads calculated.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.16.7

- An abnormal procedure present in the AFM and the AOM describes the actions to take in the case of uncommanded action of the nose wheel steering system. It consists in:

- using the rudder and differential braking to control and correct the flight path;

- positioning the PWR STEER switch to OFF in order to disable the steering system.

- This procedure, which was added by Gulfstream to the AFM and AOM as a result of the accident in Eagle (Colorado, USA) in 2004, is not included in the rest of the operational documentation: the QRH (published by the manufacturer, which includes all the abnormal procedures in the AFM), the CRH or the IPTM.

- Information to operators - Maintenance and Operations Letter (MOL). Following the accident in Eagle, Gulfstream had sent a letter dated December 14, 2004 to all GIV operators to draw their attention to the fact that control problems of the steering system may arise during landing and be undetectable or undetected until they have occurred. The letter introduces the new "Uncommanded Nose Wheel Steering" procedure. It states that it will be introduced in the next update of the AFM and indicates that the vigilance of crews must be increased so that they can react appropriately in case of an occurrence of this event: they must be able to apply full deflection of the rudder pedals and maximum input on the brake pedal. Gulfstream draws their attention to the adjustment of the seats and the position of the feet when landing.

- This letter was not sent to all training organizations, in particular CAE Simuflite. UJT indicated they were not aware of this letter.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.17.5.5

The [Cockpit Voice] recording started during taxiing in Nice. This made it possible to determine, during the flight:

- the atmosphere between the pilots was good and the observable stress level low;

- the copilot read the approach chart to Le Castellet during the cruise; he informed the Captain that he had not checked the approach chart before the flight;

- the crew mentioned the proximity of the terrain, the need to reduce speed and anticipate the configuration, and the short runway length;

- several checklists were not done or requested;

- the “before landing“ checklist was done in an incomplete manner: the PF requested the extension of the landing gear, called the checklist and then requested the extension of the flaps to their landing position. The PM performed these actions then called out: “ok, gear down, three green, checklist is complete“;

- the noise level of the first touchdown of the nose gear was abnormally high;

- spectral analysis showed that after the first touchdown, the speed of the nose gear wheels, which were no longer in contact with the ground, was close to the speed of the aeroplane at that time; this speed then gradually decreased, to about the same level as that observed during the take-off from Nice, for example;

- there was no verbal exchange between the crew members during the aeroplane’s landing roll.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.11.2

- during the flight, numerous checklists were not carried out or called for. The "before landing" checklist was carried out in an incomplete manner;

- the crew omitted to arm the ground spoilers during the approach and they did not detect this in flight;

- not being armed, the ground spoilers did not deploy on main landing gear touchdown and the crew did not notice it;

- the non-deployment generated a low load on the landing gear causing a temporary loss of on-ground condition of the main landing gear;

- the temporary loss of the on-ground condition inhibited the deployment of the thrust reversers for seven seconds and caused the triggering of the MASTER WARNING alarms;

- the low load on the landing gear prevented effective braking;

- the deceleration was relatively low on the first two thirds of the runway;

- the crew applied a strong nose-down input that generated an unusually high load, for a short period, on the nose gear;

- following the second touchdown of the nose gear the aeroplane veered to the left due to an orientation to the left of the nose gear;

- the leftwards orientation of the nose gear could have been caused by a left input on the tiller or by a failure in the steering system;

- the crew immediately responded to the lateral deviation with an input on the rudder pedals and differential braking but were unable to maintain control of the aeroplane; they did not set the PWR STEER switch to OFF when the aeroplane was on the runway;

Source: BEA Report, ¶3.1

The Captain was employed by American Airlines between 1977 and 2008. He had been flying as Captain on Boeing B777s since 2003. After retiring from American Airlines, he was hired as a pilot on a part-time basis by UJT on 25 September 2010. He followed the UJT operator’s conversion training (lasting three days between 25 and 29 October 2010) and then passed the type rating course for the Gulfstream GIV within the CAE Simuflite training organization based in Dallas (Texas) in November 2010.

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.5

Several UJT pilots who flew with the Captain said he was not accustomed to short flights. They also agreed in stating that he was not comfortable with handling the FMS, carrying out checklists and in his role as PM in general. He had a strong personality and sometimes imposed his decisions. Two copilots who flew with him reported that he had already forgotten to arm the ground spoilers. One of them said that during a landing, the Captain, although PM during the flight, had pushed the controls during the landing roll so that "the directional control was more effective".

Source: BEA Report, ¶1.18.2

4

Cause

Forgetting to arm the ground spoilers delayed the deployment of the thrust reversers despite their selection. Several MASTER WARNING alarms were triggered and the deceleration was low. The crew then responded by applying a strong nose-down input in order to make sure that the aeroplane stayed in contact with the ground, resulting in unusually high load for a brief moment on the nose gear. After that, the nose gear wheels deviated to the left as a result of a left input on the tiller or a failure in the steering system. It was not possible to establish a formal link between the high load on the nose gear and this possible failure. The crew was then unable to avoid the runway excursion at high speed and the collision with trees.

The accident was caused by the combination of the following factors:

- the ground spoilers were not armed during the approach;

- a lack of a complete check of the items with the "before landing" checklist, and more generally the UJT crews’ failure to systematically perform the checklists as a challenge and response to ensure the safety of the flight;

- procedures and ergonomics of the aeroplane that were not conducive to monitoring the extension of the ground spoilers during the landing;

- a possible left input on the tiller or a failure of the nose gear steering system having caused its orientation to the left to values greater than those that can be commanded using the rudder pedals, without generating any warning;

- a lack of crew training in the "Uncommanded Nose Wheel Steering" procedure, provided to face uncommanded orientations of the nose gear;

- an introduction of this new procedure that was not subject to a clear assessment by Gulfstream or the FAA;

- failures in updating the documentation of the manufacturer and the operator;

- monitoring by the FAA that failed to detect both the absence of any updates of this documentation and the operating procedure for carrying out checklists by the operator.

Source: BEA Report, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile (BEA) Accident Report on 13 July 2012 at Le Castellet aerodrome (83) to the Gulfstream GIV aeroplane registered N823GA, Published October 2015

NTSB Preliminary Information, DCA12RA110, Gulfstream GIV, N823GA, Le Castellet Airport, France, 13 July 2012