Conspiracy theories abound, helped of course by the fact the U.S., which had investigative responsibilities, punted and gave the investigation to the ICAO. This was only the second time this had ever happened and the results have been shrouded in secrecy ever since.

— James Albright

Updated:

2013-07-06

Of course the real cause was a Russian fighter pilot eager for a "kill" and a Russian command and control system unable to make timely decisions. But that doesn't help the hapless crew now does it?

I have many hours in this exact model of Boeing 747 with the same inertial navigation system. The theory that they failed to switch from heading mode to lateral navigation along inputted waypoints seems right to me. Looking at the totality of other Korean airlines mishaps, it seems like just the kind of thing they would do.

Regardless of which of the theories you subscribe to, two things are clear.

- You need to maintain situational awareness when using flight automation, and

- You need to plot navigation performance as a crosscheck of all your other procedures.

Everything here is from the references shown below, with a few comments in orange. Many will no doubt be angered by my complete disregard for the various theories out there. They could be true, I don't know. But if this was caused by a navigation error, I need to focus on that. Improving pilot procedures and techniques, after all, is the purpose of this website.

1

Accident report

- Date: 01 SEP 1983

- Time: 03:26

- Type: Boeing 747-230B

- Operator: Korean Air Lines

- Registration: HL7442

- Fatalities: 23 of 23 crew, 246 of 246 passengers

- Aircraft fate: Destroyed

- Phase: En route

- Airport (Departure): Anchorage International Airport, AK (ANC) (ANC/PANC), United States of America

- Airport (Destination): Seoul-Gimpo (Kimpo) International Airport (SEL) (SEL/RKSS), South Korea

2

Narrative

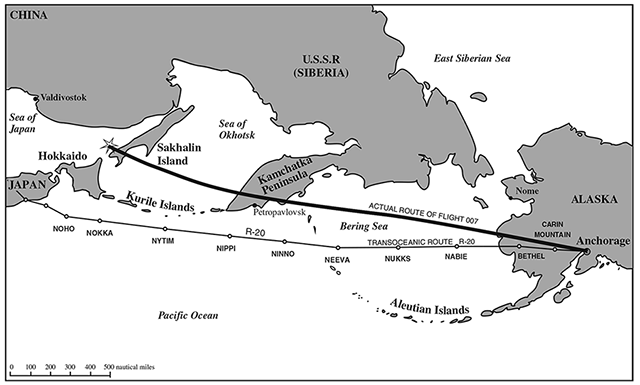

- Flight 007, which originated in New York City, was now ready and fueled up for the long transpacific flight to Seoul. After a long takeoff roll, the heavy aircraft, full of cargo, fuel, and passengers, pitched up and climbed slowly into the gloomy morning sky. After reaching 1,000 feet, the white aircraft rolled gently to the left and began its westbound flight. Leaving Anchorage behind, Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was given the following air-traffic-control instruction: fly directly to the Bethel navigational waypoint and then follow transoceanic track R-20 all the way to Seoul (see figure 4.1).

- The aircraft followed the instructions and changed its heading accordingly. But as minutes passed, the aircraft slowly deviated to the right (north) of its intended route, flying somewhat parallel to it, but not actually on it. [ . . . ] In the cockpit, the flight crew reported to air traffic control that they were on track, flying toward Nukks, Neeva, Ninno, Nippi, Nytim, Nokka, Noho—a sequence of navigation waypoints on route to Seoul.

Source: Degani, ch. 4

With the airplane running parallel to the track, the INS could very well have sequenced from point to point, fooling the crewmember assigned the task of making position reports that all was well. This crewmember was probably junior and may not have known to (or dared to) check the latitude and longitude actually flown against the filed track.

- As the flight progressed and the divergence between the actual aircraft path and the intended flight route increased, the lone jumbo jet was no longer flying to Seoul. Instead, it was heading toward Siberia. An hour later, Flight 007, still over international waters, entered into an airspace that was closely monitored by the Soviets. In the very same area, a United States Air Force Boeing RC-135, the military version of the commercial Boeing 707 aircraft, was flying a military reconnaissance mission, code named "Cobra Dane." Crammed with sophisticated listening devices, its mission was to tickle and probe the Soviet air defense system, monitoring their responses and communications. The U.S. Air Force aircraft was flying in wide circles, 350 miles east of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Source: Degani, ch. 4

The actual name of the airplane's mission was "Cobra Ball." Cobra Dane refers to a ground based radar system based on Shemya.

- Kamchatka is a narrow and mountainous peninsula that extends from Siberia to the Bering Sea. [ . . . ] In those mountains, the Soviets installed several military radars and command centers. Their purpose was to track U.S. and international flight activities over the Bering Sea. [ . . . ] As the U.S. Air Force Boeing 707 aircraft was circling over the frigid water in the dark of the night, purposely coming in and out of radar range, Soviet radar operators were monitoring and marking its moves. And then, during one of the temporary disappearances of the reconnaissance aircraft from the radar screen, the Korean airliner came in. The geographical proximity between the two large aircraft led the Soviet air-defense personnel sitting in front of their radar screens to assume that the target that reappeared was the military reconnaissance aircraft. They designated it as an unidentified target.

- The Korean airliner continued its steady flight toward Kamchatka Peninsula. In the port town of Petropavlovsk, on the southern edge of the peninsula, the Soviets had a large naval base with nuclear submarines. KAL 007 was heading straight toward it. But the pilots could not see Kamchatka, because although the night sky above them was clear, everything below them was pitch dark. When the jetliner was about 80 miles from the Kamchatka coast, four MiG-23 fighters were scrambled to intercept it. The fighter formation first flew east for the intercept, then turned west and started a dog chase to reach the fast and high-flying Boeing 747. Shortly after, low on fuel, the fighters were instructed to return to base. The Korean jetliner, now 185 miles off track, crossed over the Kamchatka Peninsula and continued into the Sea of Okhotsk. Over international waters, safe for the moment, the large aircraft was heading, unfortunately, toward another Soviet territory—Sakhalin Island—a narrow, 500-mile-long island off the Siberian coast, just north of Japan.

- On the radar screen inside a military control center on Sakhalin Island, the approaching blip was now designated as a military target, most likely an American RC-135 on an intrusion mission. Because of this military designation, the rules for identification and engagement were those reserved for military action against Soviet territory (and not the international rules for civil aircraft straying into sovereign airspace). Apparently, there had been more than a few such airborne intelligence-gathering intrusions by U.S. aircraft into Soviet airspace in the preceding months, not to the liking of Soviet air-defense commanders.

- As the target approached Sakhalin Island from the northeast, two Soviet Su-15 fighters, on night alert, were scrambled from a local military airbase toward the aircraft. The Soviet air defense system had fumbled in its first encounter with the intruding aircraft, but was unlikely to miss the second chance. A direct order was given to local air-defense commanders that the aircraft was a combat target. It must be destroyed if it violated state borders.

- About 20 minutes later, Flight 007 crossed into Sakhalin Island. The flight crew—sitting in their womb-like cockpit, warm and well fed—had no idea they were flying into the hornet’s nest. At 33,000 feet, while the pilots were engaged in a casual conversation in the lit cockpit, monitoring the health of the four large engines, and exchanging greetings and casual chat with another Korean Air Lines aircraft also bound for Seoul—a gray fighter was screaming behind them to a dark intercept. The fighter pilot made visual contact, throttled back, and was now trailing about four miles behind the large passenger aircraft. The fighter pilot saw the aircraft’s three white navigation lights and one flickering strobe, but because of the darkness was unable to identify what kind of an aircraft it was.

- The identification of the target was a source of confusing messages between the fighter pilot, his ground controller, and the entire chain of air-defense command. When asked by his ground controller, the pilot responded that there were four (engine) contrails. This information matched the air-defense commanders’ assumption that this was an American RC-135, also with four engines, on a deliberate intrusion mission into Soviet territory. The Soviets tried to hail the coming aircraft on a radio frequency that is reserved only for distress and emergency calls. But nobody was listening to that frequency in the Boeing 747 cockpit. Several air-defense commanders had concerns about the identification of the target, but the time pressure gave little room to think. Completely unaware of their actual geographical location, the crew of KAL 007 were performing their regular duties and establishing routine radio contact with air traffic controllers in Japan. Since leaving Anchorage they were out of any civilian radar coverage. After making radio contact with Tokyo Control, they made a request to climb from 33,000 feet to a new altitude of 35,000 feet. Now they were waiting for Tokyo’s reply.

- Meanwhile, a Soviet air-defense commander ordered the fighter pilot to flash his lights and fire a burst of 200 bullets to the side of the aircraft. This was intended as a warning sign, with the goal of forcing the aircraft to land at Sakhalin. The round of bullets did not include tracer bullets; and in the vast and empty darkness the bullets were not seen or heard by the crew of KAL 007. The four-engine aircraft continued straight ahead. Flying over the southern tip of Sakhalin Island, Soviet air defense controllers were engaged in stressful communications with their supervisors about what to do. The aircraft was about to coast out of Soviet territory back into the safety of international waters; the target was about to escape clean for the second time. The Sea of Japan lay ahead—and 300 miles beyond it, mainland Russia and the naval base of Vladivostok, the home of the Soviet Pacific fleet.

- The air-defense commander asked the fighter pilot if the enemy target was descending in response to the burst of bullets; the pilot responded that the target was still flying level. By a rare and fateful coincidence, just as the aircraft was about to cross into the sea, KAL 007 received instructions from Tokyo air traffic control to "Climb and maintain 35,000 feet." As the airliner began to climb, its airspeed dropped somewhat, and this caused the pursuing fighter to slightly overpass. Shortly afterward, the large aircraft was climbing on its way to the newly assigned altitude. The fighter pilot reported that he was falling behind the ascending target and losing his attack position. This otherwise routine maneuver sealed the fate of KAL 007. It convinced the Soviets that the intruding aircraft was engaging in evasive maneuvers.

- "Engage afterburners and destroy the target!"

- Seconds later, the fighter aircraft launched two air-to-air missiles toward the target. One missile exploded near the vulnerable jet. The aircraft first pitched up. [ . . . ] The captain and his copilot tried helplessly to control the aircraft and arrest its downward spiral. Two minutes later, the aircraft stalled out of control and then plummeted down into the sea. It impacted the water about 30 miles off the Sakhalin coast.

Source: Degani, ch. 4

3

Analysis

- Two minutes and ten seconds after takeoff, according to the flight data recorder, the pilots engaged the autopilot. When the pilot engaged the autopilot, the initial mode was HEADING. In this mode, the autopilot simply maintains the heading that is dialed in by the crew. The initial heading was 220 degrees (southwesterly). After receiving a directive to fly to Bethel waypoint, the pilot rotated the ‘‘heading select knob’’ and dialed in a new heading of 245 degrees. The autopilot maintained this heading until the aircraft was shot down hours later.

- Using HEADING mode is not how one is supposed to fly a large and modern aircraft from one continent to another. In HEADING mode, the autopilot maintains a heading according to the magnetic compass, which, at these near arctic latitudes, can vary as much as 15 degrees from the actual (true) heading (not to mention that this variation changes and fluctuates as an aircraft proceeds west). Furthermore, simply maintaining a constant heading does not take into account the effect of the strong high-altitude winds so prevalent in these regions, which can veer the aircraft away from its intended route. The aircraft was also equipped with an Inertial Navigation System (INS).

Source: Degani, ch. 4

4

Cause

There are two plausible theories for why KAL 007 wandered off course into Russian airspace.

- They may have left their autopilot in heading mode, neglecting to switch to INS mode.

- They were using a 9 waypoint INS that limited them to 9 waypoints and may have omitted the middle waypoints and entered only the first 8 waypoints and left the 9th to provide an approximate ETA for their destination. This was a common technique back then and required that once a waypoint is no longer needed (it is at least two waypoints behind) it be reprogrammed. They may have forgotten to do this and the airplane simply turned direct to their destination once waypoint number 8 was passed.

References

(Source material)

Degani, Asef, Taming Hal: Designing Interfaces Beyond 2001, St. Martin's Press, 12 Feb 2004