For most pilots, becoming a captain at a major airline is one step among many along the path to becoming a better aviator. It isn’t the end of the journey of learning, but a gateway to more lessons to come. For some pilots, however, it is the ultimate goal, the top rung of the so-called pilot pyramid. The title itself demands the respect from all others without it. All hail Captain Vainglory.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-05-15

vainglory (noun)

vain·glo·ry | \ ˈvān-ˌglȯr-ē \

1. Excessive pride in oneself or one’s achievements; boastful vanity.

2. Empty or worthless glory; an overestimation of one’s own importance.

This kind of pride is natural in younger pilots but should be temporary because sooner or later reality hits: there will always be better pilots out there and no matter how good you are, you have room to improve. A self-aware pilot realizes this and conducts him or herself with a sense of humility.

Unfortunately, not all pilots are capable of this kind of self-awareness. They are trapped in their own narcissism and any evidence that they are wrong or that they have more to learn falls of deaf ears. A healthy first officer learns from their captains and peers and accepts evidence of their own shortcomings as opportunities to improve. A vainglory first officer believes they are being unfairly persecuted and pines for the days they will be the captain so they can bully others as they believed they themselves were bullied.

And this leads us to the case of Southwest Airlines (SWA) Flight 345. We’ll first cover what happened, as related by the NTSB Aircraft Investigation Final Report, and discover the accident was caused by the captain. The captain was fired by Southwest Airlines, so problem solved. Right? Not so.

Date: Monday 22 July 2013

Time: 17:44

Type: Boeing 737-7H4

Operator: Southwest Airlines

Registration: N753SW

Fatalities: 0 / 149

Aircraft damage: substantial, written off

Destination airport: New York-La Guardia Airport, NY (KLGA).

1 — What happened: if all you read is the Aviation Investigation Final Report

2 — Southwest Airlines procedures: how it should be done

3 — Boeing 737-700 landings, flaps 30 versus 40

4 — What happened: digging deeper into the docket

5 — Summarizing the “what” before the “why”

9 — Sidebar: was Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) a factor?

1

What happened

(if all you read is the Aviation Investigation Final Report)

The approach of the Southwest Airlines (SWA) Boeing 737 was going well until the captain, who was the Pilot Monitoring (PM) realized the flaps were not set to 40, as planned. The Flight Data Recorder revealed they were at about 600 feet, 400 feet below their stable approach height. They should have gone around. The captain selected flaps 40 and the crew continued. As they descended through 200 feet, the aircraft was above glideslope. They should have gone around. The captain called, “get down” repeatedly. At 27 feet, the captain announced, “I got it.” The captain took control but didn’t raise the nose. The nose gear hit first, collapsing. The aircraft came to a stop. There were injuries, but no fatalities. Along the way to the crash, the captain failed to follow Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) at several points during the flight. [Aviation Investigation Final Report pp. 1 – 2]

The captain was hired by SWA in October 2000, upgraded to captain seven years later, and had 12,522 hours total flight time, 7,907 in type, of which 2,659 were as captain. “The chief pilot received no complaints regarding the captain after she received refresher training.” [Aviation Investigation Final Report, p. 5]

The weather at La Guardia at the time was good, winds 040/8, visibility 7 miles, few clouds at 3,000 feet, scattered clouds at 5,000 feet, ceiling broken at 7,500 feet and overcast at 13,000 feet. [Aviation Investigation Final Report, p. 8]

The aircraft was substantially damaged. [Aviation Investigation Final Report, p. 5]

The report discusses SWA stabilized approach procedures, transfer of aircraft control procedures, and the normal manipulation of switches, gear, and flaps. All of these appear conventional and all appear to have been violated by the captain. The first officer was complicit, of course, but the report leaves no doubt as to blame:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The captain's attempt to recover from an unstabilized approach by transferring airplane control at low altitude instead of performing a go-around. Contributing to the accident was the captain's failure to comply with standard operating procedures.

[Aviation Investigation Final Report p. 2]

Problems with the Aviation Investigation Final Report

The Aviation Investigation Final Report is the NTSB’s version of what happened, further analysis, and a pronouncement of probable cause. The greater the loss of life, property, or newsworthiness, the greater the detail in the report. There may also be political concerns. Whatever the reasons, this Final Report leaves out more than it includes. Based on the 13 pages of the report, both pilots were qualified, the aircraft was airworthy, the weather wasn’t too challenging, and it all happened because the captain grabbed the aircraft from the first officer 27 feet off the ground. The captain didn’t follow Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): missing call outs, not enforcing stable approach procedures, and failing to go around. All of that is true, but if that is all you read, you only discover what happened, not why. And without the why, we don’t fully understand how to prevent recurrence.

Fortunately, the NTSB also publishes online more information in the form of a docket. You can find this at ntsb.gov, select the “Investigations” tab, further select “Investigations Docket.” From there you will see a search dialog. Entering the NTSB Accident ID, in this case “DCA13FA131,” gives you all the information that follows.

2

Southwest Airlines procedures

(how it should be done)

To fully understand the problems during the flight that led to the crash, we need to understand SWA stabilized approach procedures, the transfer of aircraft control procedures, and the division of PF / PM automation duties.

Stabilized approach procedures

Stabilized approach procedures at SWA appear to adhere to what most of the industry uses. According to the Assistant Chief Pilot:

SWA’s stabilized approach criteria was at 1,000 feet – airplane fully configured with gear down and landing flaps set. Airspeed within plus 10 to -5 knots of target airspeed, sink rate no more than 1,000 feet per minute [can be briefly exceeded], and within 1 dot of glideslope and localizer. More than 1 dot deviation off glideslope or localizer requires a callout on glideslope. On visual approach with good tailwind, sink rate might be more than 1000 fpm on the way down but it would typically be briefed that beforehand. If the PM said “sink rate”, the response from the PF should be “correcting.” If it was a vertical speed approach, the airplane had to be configured by the FAF.

If landing flaps were supposed to be at 40 and when passing through 1,000 feet you were at 30 flaps and then selected 40 flaps, that may be okay. Selecting 40 flaps at 800 feet would not be acceptable so a go-around would be required.

[Interview Summaries, p. 28]

Transfer of aircraft control procedures

The transfer of aircraft control procedure at SWA also appears standard:

(PF) Transfer aircraft control, when necessary.

Transfer of aircraft control must be concise and clear. There can be no doubt about who is controlling the aircraft. Therefore, when aircraft control is transferred, announce, "You have the aircraft." The Pilot assuming aircraft control acknowledges, "I have the aircraft."

(PM) Assume aircraft control, when necessary.

If there is a need to take control of the aircraft for safety reasons or required by specific procedures, announce, "I have the aircraft." The other Pilot acknowledges, "You have the aircraft."

[Aviation Investigation Final Report p. 12 ]

The division of PF / PM automation duties

Gear and flaps

Section 3.2.3 in chapter 3 of the Southwest Airlines FOM provides guidance on who, between the PF and PM, should manipulate controls and when they should do so. In flight, the PM normally moves the landing gear and flap controls upon the command of the PF. Prior to moving the landing gear or flap handle, the PM checks the airspeed to ensure that it is in the normal operating range for the requested aircraft configuration. After checking the airspeed, the PM accomplishes the following steps:

- Repeat the command.

- Select the landing gear or flaps to the commanded position.

- Ensure the landing gear or flaps move to the commanded position.

[Aviation Investigation Final Report p. 12 ]

Mode Control Panel (MCP)

The PF maintains responsibility for the aircraft flight path and speed; this responsibility is never delegated to an automatic system. The PF chooses the most appropriate automation and flight director guidance for the task. This includes reverting from FMC guidance and selecting more appropriate lateral and vertical modes from the MCP or reverting to hand-flying for direct control of the aircraft flight path and thrust. [Human Factors, p. 10]

This too is fairly standard. If the First Officer is the PF, the first officer flies the airplane and directs the Captain / PM to make changes to the MCP. The Captain / PM should not make any changes without the First Officer / PF’s direction. “Flies the airplane” includes the decisions of what speed to fly, what automation choices to make, when to configure, and so on. If the captain disagrees with these decisions, the captain can make suggestions or take control of the aircraft. If, for example, the captain wants the first officer to slow down, the captain should say that and not simply grab the speed dial of the automation.

3

Boeing 737-700 landings, flaps 30 versus 40

Most landings in the 737-700 at SWA are made using flaps 30, but using flaps 40 was also used if the conditions dictated. The Assistant Chief Pilot was asked about how the landings differ:

For a flaps 40 landing the nose would not be as high as flaps 30. You had to fly the nose to the runway. Pilots might pull power off at around 8-10 feet with flaps 30. With flaps 40 you did not pull power till just before touchdown because the airplane was going to come out of the sky. The technique was to hold deck angle and just prior to touchdown pull the power.

He was asked if it would concern him if someone pulled the power at 100 feet with flaps 40 and he responded “Yes, that’s one time I would say I have the aircraft.”

[Interview Summaries (with Assistant Chief Pilot), p. 28]

4

What happened

(digging deeper into the docket)

A concern about the weather

The flight received brief radar vectors around thunderstorm activity in the arrival area. The weather was between them and the airport, having moved through earlier in the day. The captain thought (correctly) that the runway was dry, but decided to use wet in the performance computer, “to err on the side of safety.” [Interview summaries, p. 2] She was concerned about landing on Runway 4 because “it was a short runway, they had a tailwind, and there was water at the end of the runway.” [Interview summaries, p. 7] They were given a brief hold and used the time to discuss fuel and alternates with dispatch through ACARS. The first officer briefed the approach, planning on a visual to Runway 4, backed up by the ILS, and the “3” setting on the autobrakes, since the “2” setting was flagged by the Onboard Performance Computer was flagged as insufficient for the wet runway. The captain wanted to use flaps 40 as a result. [Operational Factors, p. 5] She didn’t recall running the numbers for flaps 30. [Interview summaries, p. 10]

After the approach briefing, they were initially given a holding with an expected clearance time of about 40 minutes. But they only did one turn and were then given clearance on course. [Interview summaries, p. 16]

The captain had only flown into LGA once before, about 6 months prior. [Interview Summaries, p. 7] The first officer had flown into LGA 3 to 4 times that year. [Interview Summaries, p. 12] The first officer’s plan was to keep the speed up until close to the airport or directed to do so. This is normal procedure in the NYC area, due to traffic volume, but it appeared to make the captain anxious. “As he was slowing from 250 knots to approach speeds, she was the one spinning the MCP dials without him asking her to set his speeds. As he was about to call for a speed, she would go ahead and dial it in. It was the standard speeds as they lowered flaps. This was not normal; especially in the terminal area, this was nonstandard. He thought she just did it, and he did not remember her stating she was doing it.” He noted that she would often set speeds and altitudes before he asked for them, as required by SOP. [Interview Summaries, pp. 16 - 17]

The flaps

The first officer said that passing the final approach fix they were configured with the landing gear and flaps 30. “Some distance past the final approach fix,” the captain noticed the flaps were not at 40, as briefed and as was used for the performance calculations. The captain said she notified the first officer and once cleared, selected flaps 40. The first officer said she called out “flaps forty” and set the flaps to 40, “without any input or acknowledgement from him.” [Operational Factors, p. 5] The cockpit voice recorder shows she said “oh we’re forty,” he said “Oh there you go,” and she moved the flap handle. [Cockpit Voice Recorder, p. 12-45]

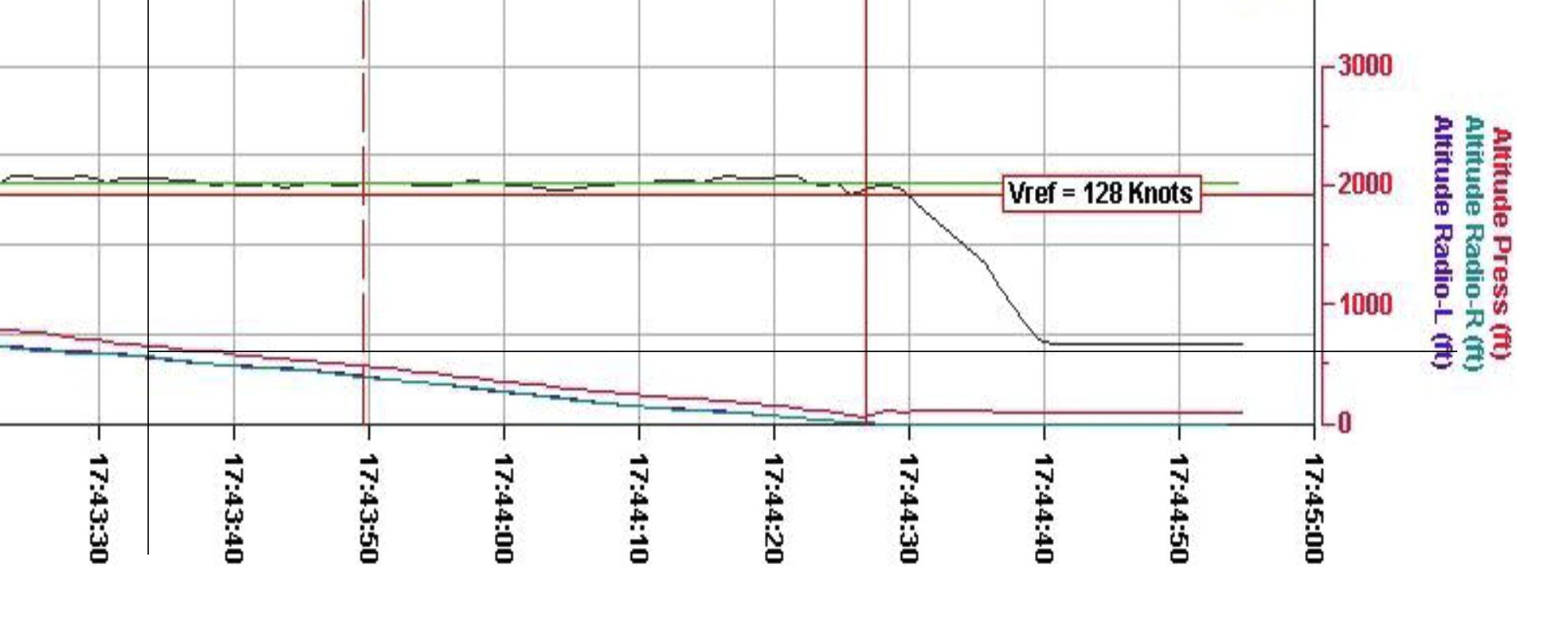

The first officer said they were close to 1,000 feet AGL when the flaps were reset. The captain said it was a “good time” prior to the 500 foot call out. [Operational Factors, p. 12] Based on CVR sounds, the flap handle was moved at 17:43:32.1 and that is corroborated by the Flight Data Recorder. At the time the flap handle was moved, the aircraft appeared to be at 600 feet, about what the captain thought but well below the stable approach criteria requiring a go around. [Flight Data Recorder, pp. A-1, A-3]

The approach from 500 feet

The first officer stated that the autopilot was coupled to the ILS, the autothrottles were engaged during the approach, and the sink rate was about 700-800 feet per minute. At around 500 feet, he crosschecked the winds and recalled that there was a slight crosswind of around 11 knots. At about 500 feet, he disconnected the autopilot and autothrottles and took over manual control.

[Operational Factors, p. 6]

The throttle pull

The first officer said that out of the corner of his eye he noticed that the captain appeared to be somewhat uncomfortable with the approach. As they crossed over the runway overrun, he noticed that the PAPI indicated 3 white lights and one red, which meant that they were a little high on the glidepath. He knew that he would need to make a slight correction to land in the touchdown zone. He said that he then felt the captain’s hand on top of his on the throttles, and she pulled his hand and the throttles back retarding the throttles to what felt like the idle position. He said that he did not recall her making any comments, before, or during her retarding the throttles. The first officer said that he had never had a captain put his/her hand over his on the throttles during an approach, although some captains would guard the throttles by placing their hand below his behind the throttle levers. He said he never had a captain pull the throttles back on him while he was flying an approach.

[Operational Factors, p. 6]

[The captain] said that over the threshold, she verbalized that they had to get the airplane down, and she put her hand over the first officer’s hand on the throttle, but was not touching his hand. [Operational Factors, p. 6]

17:44:14.4 Captain: one hundred.

17:44:15.8 Captain: gotta get [unintelligible]. [unintelligible]

17:44:17.7 Captain: get down. get down. get down.

17:44:20.6 Captain: get down.

17:44:23.0 Captain: I got it.

17:44:23.6 First Officer: okay you got it.

17:44:26.0 Captain: [sound similar to inhalation] [unintelligible].

17:44:26.8 Cockpit Area Microphone: [sound of impact]

[Cockpit Voice Recorder, p. 12-47]

The first officer said the captain pulled the throttles to idle before saying “I got it,” which happened at 17:44:23.0, at 27 feet AGL.

“I got it”

The captain said that she was not completely sure what the airplane pitch attitude was when she took control, but she said she knew it was not what it should have been for a 40º flaps landing. She thought the pitch attitude should have been around 5º, but it was less, and she said she increased back pressure on the controls to raise the nose and she was increasing power as the airplane dropped to the runway.

[Operational Factors, p. 7]

The Flight Data Recorder belies this claim:

The aircraft’s pitch has begun to enter a negative (nose down) trend which continues to decrease to a minimum airborne value of -3.87 degrees. Just prior to touchdown, Control Column Position for Captain and First Officer remain near zero.

[Flight Data Recorder, p. 4]

The commanded column deflection relaxed to neutral deflection at 27 feet RA (time 7786 seconds) and remained in the neutral position until the airplane came to a stop.

[Boeing Performance Analysis, p. 3]

5

Summarizing the “what” before the “why”

As stated by the Final Report and verified by additional information in the docket, we see that the crew forgot to set the planned flap setting prior to the SOP stable approach height and failed to go around when they realized the mistake. The captain initiated a change to the flap setting without first getting first officer occurrence, operated the throttles while still the Pilot Monitoring, and failed to properly fly the aircraft once she had taken control. The first officer failed to call for a go around throughout the process, which would have been the correct reaction several times during the approach. All of that is “what” happened. Discovering the “why” depends a great deal on asking hard questions about the captain.

6

Captain Vainglory

The final report does not use the captain’s name, but her name is cited in the accident docket. I don’t see much use in that. She was terminated by SWA and her pilot certificate “was requested” to be put “on deposit,” according to the FAA, SWA Aviation Principal Maintenance Inspector. [Interview Summaries, p. 51] “On deposit” doesn’t mean her certificate was revoked, only that she would be unable to fly until taking a 709 “Reexamination of Airman Certificate” check ride.

I will instead call her Captain Vainglory to emphasize that this is a real person, not a statistical aberration of some sort. I want to paint a picture of the captain’s personality to alert pilot readers that there are more such pilots out there. I think this will be useful when looking at the lessons learned, to follow.

Note: what follows are my opinions gathered from evidence in the accident docket. I offer these opinions only to build a case for the lessons learned, which I hope will help pilots with similar issues to self-correct and pilots who notice pilots like Captain Vainglory to encourage them to either seek help or be removed from the ranks.

A weak resume

Future Captain Vainglory was hired on October 12, 2000, eleven years after receiving her private pilot certificate. She was working as a CFI until 1998 when she was hired by Ameriflight to fly the Piper Lance, the Piper Navajo Chieftain, and the Beech 99, all as single pilot operations. Her only turbine time was in the Beech 99, and she had no crew experience prior to SWA. To her credit, her only failure in training was on a check ride for her single engine commercial certificate. [Interview summaries, p. 1]

An average pilot in a company of excellent pilots

Pilots – airline pilots especially – are loathe to rate other pilots and are reluctant to criticize on the record. Doing so can earn them a reputation as someone who doesn’t get along and cannot be trusted to keep confidences. Combing through the docket, I was struck by the fact most of her peers called her an average pilot.

Why is being average a problem? It isn’t. I know many pilots at Southwest, most of them are outstanding pilots. So “average” at SWA is still pretty good. But if the pilot in question has poor self-esteem or a lack of confidence, it can be a very big problem when dealing with a crew. I think that was probably true with Captain Vainglory. She had convinced herself that she was as good or better than any of her first officers, evidence notwithstanding.

Average or not, she had to know she was below the standard set by many she flew with. The accident first officer, for example, had a full Air Force career which included the F-15C, F-117A, and T-38C. He was an instructor and evaluator in two of those jets. He had three combat tours and received multiple air medals. For many, if not most, being paired with such a pilot bodes well for a good trip. I think for a pilot with self-esteem problems, such a pairing can produce jealousy and a need to prove oneself.

The “Passdown” Files

First Officer Vainglory upgraded to captain in August 2007. Three years later, she was directed to attend additional training in Crew Resource Management (CRM) because of complaints about her received by the chief pilot from first officers who had flown with her.

The chief pilot at the Oakland Southwest Airlines office, where Captain Vainglory was based, kept memos called “passdown files” to document personnel problems. A summary of the files from late 2009 to early 2010 noted the following comments about Captain Vainglory:

- “Four stripe syndrome”

- “Attitude/personality”

- “Does not solicit input from FO or allow FO in the decision process”

- “Not setting tone/Poor Flt Deck environment”

- “Insecure in abilities/leadership”

- “Great w/Flight Attendants but CRM on Flt Deck not there”

- “Need to understand team concept/she makes all the decisions”

- “Hung up on Woman in Aviation and women lib discussion”

- “Flys [sic] the aircraft for the FO”

- “Doesn’t like to be questioned or challenged”

- “Harsh approach/coughs orders/snaps response”

- “Communication lacking”

[Human Factors Report, p. 3]

The chief pilot met with Captain Vainglory in January 2010 to discuss these issues.

The passdown file created by the chief pilot following the meeting stated that during the meeting she was initially defensive and argued each point. For example, he discussed with her an event in which she had briefed a single-engine return back to MDW, but the first officer had suggested ORD because the OPC would not allow a flaps 15 landing with wet-good braking at MDW; and her response to the first officer was “ok, if you want to go land in that mess.” When the chief pilot shared that scenario with the accident captain, she said the FO was an “a**hole from day one, and was always challenging her.” The chief pilot further wrote in the passdown file that his impression was that the captain was insecure in the left seat and regarded input from the FO as a challenge to her authority, felt threatened, and responded defensively.

[Human Factors Report, pp. 3 - 4]

The chief pilot directed additional CRM training, which appeared to go well. According to Captain Vainglory’s CRM session instructor: “She knew that the captain had problems with more than one FO. She also thought one complaint was that the captain was dismissive with FOs; poor communication processes with her FOs might be another way to put it.” [Interview Summaries, p. 37]

A follow up conversation between the chief pilot and the captain about a week after the training indicated she was pleased with the training. The chief pilot also stated that an FO that had previously flown with the accident captain told him that she was much improved after the training. The CRM instructor contacted the captain about a month after the training and the captain felt that things were going well with the FOs she flew with. The chief pilot had received no repeat complaints regarding the accident captain since the training.

[Human Factors Report, p. 4]

“Avoidance Bidding”

SWA had an avoidance bid system, which was mandated by the collective bargaining agreement between SWA and the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association and similar to systems operated by other airlines, that allowed first officers to designate up to three captains that they did not want to be paired with for their monthly bid sequence of trips. If the system paired a first officer with one of his avoided captains, it would remove the first officer from that trip and give him another trip. A first officer would only enter the employee number into the system and it did not request a reason be given for avoiding a captain. This system was not actively monitored by SWA and data was accessed only with approval by the vice president of flight operations. In 2009, the captain had an average of 4.8 avoidance bids against her each month (ranging from 4 to 6 each month). During that same year, 15.9% of the 353 OAK-based captains had one or more avoidance bids and the average of those captains was 3.1 bids per month. In the 12 months preceding the accident, the average number of avoidance bids against the captain was 6.9 (ranging from 5 to 9 each month). During that same time period, 15% of the 367 OAK-based captains had one or more avoidance bids and the average of those captains was 2.8 bids per month.

[Human Performance, p. 4]

It appears Captain Vainglory had significantly more avoidance bids than other captains. She was aware of the avoidance bidding system and had used it as a first officer and that first officers had used it against her as a captain. She said the system should be anonymous but it was not, at SWA it was a tool “to label and hurt certain people.” [Interview summaries, p. 63]

A “Dunning-Kruger” graduate

How can we explain an “average” (at best) pilot who believes she can ignore stable approach rules and salvage an approach from just 27 feet above the runway?

Psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger first described what has become known as the “Dunning-Kruger” effect in a 1999 study called, “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” They found that people with low ability or knowledge tend to overestimate their own competence and underestimate the competence of others. Meanwhile, those who are highly skilled tend to underestimate their own abilities because they assume things are easy and easy for others too. In other words: “the less you know, the more confident you are. The more you know, the more you realize what you don’t know.”

I think the kind of hubris described by the Dunning-Kruger effect can be very dangerous in pilots and Captain Vainglory was just such a pilot. Her habit of making MCP changes as the PM without PF approval beforehand illustrates her “I know better than you” thought process as well as a disdain for the first officer’s abilities.

You might wonder how an incompetent pilot can fail to understand his or her shortcomings. The answer is denial. In Captain Vainglory’s example, consider the following from her NTSB interview:

As a new captain on the line she pushed standardization, particularly pilot flying/pilot monitoring duties especially when the autopilot was not on, use of checklists, and descent planning. “They berated me.” FOs were aggressive and hostile, or if not that they were quiet and unresponsive. FOs complained that no other captain made them do those things, she was told no one liked to fly with her and she got ugly notes in her box. This went on for about 2 years; it would go away and then come back. She knew she was put on the avoidance bid list and she knew there was nothing she could do to change that perception.

[Interview Summaries, p. 65]

This went on for about two years? Let’s take her at her word, she was simply pushing for standardization, particularly pilot flying/pilot monitoring duties, ignoring those appear to be her personal shortcomings. In two years, she should have been more introspective and considered she was doing a poor job mentoring her first officers. At the very least, she should have sought counsel from other captains.

From her NTSB interview:

After about 2 years, she got called in to the assistant chief pilot’s (ACP) office and he told her that there were complaints against her, she was a terrible captain and he investigated her. She asked to read the formal complaints but he said there were none. He did not give her any examples of how to change but said if she did not change this could greatly affect her career.

[Interview Summaries, p. 65]

NTSB investigators failed to follow up with the ACP on this, or did not report that they did. I find it doubtful that he didn’t provide examples of the complaints or offer any suggestions. But I also find it credible that she may be in denial about what was actually said.

7

Lessons learned

If you read the Final Report, you may conclude there is nothing to learn here, other than to follow SOP. It appears at least one FAA inspector agrees. The SWA FAA APM sat in on SWA CRM training during a recurrent training session and said it was very good. “He thought the procedures worked well and the problem was with just one crew. At that time, he did not see what they could change to prevent similar events besides saying ‘follow your procedures.’” [Interview Summaries, p. 51]

I think there are many lessons to learn from this accident, primary of which is we need to mentor our captains more carefully. It would be tempting to say the problem is that Captain Vainglory had no crew experience, but that is also true of Air Force and Navy fighter pilots, who seem to do well in the airline environment. But those pilots come from intense environments with large pilot pools where getting along with peers is critical.

Another lesson is that avoidance lists tend to mask problems. If a first officer is witness to a captain’s truly egregious behavior, an avoidance list makes the captain someone else’s problem.

Finally, though the Final Report lays blame squarely on this captain’s shoulders, she is not alone in the blame. She was, in my view, a bad captain. But she didn’t have to be, the airline, the chief pilot, and her peers allowed her to become a bad captain. First officers want to get along and don’t want to be labelled as complainers. But had more of them spoken up, Captain Vainglory may have been made less vainglorious. Had the chief pilot not just scheduled her for additional CRM training but instead made it a point to interview several of her first officers, he may have better understood the problem.

8

My recommendations

- Newly hired pilots should be evaluated for maturity, as displayed by their ability to get along as crewmembers. Something like an Initial Operating Experience evaluation after a year of employment may help identify problem pilots before they are released from probation.

- Southwest Airlines should more closely correlate their Flight Operations Quality Assurance (FOQA) data to track stable approach compliance among their crews. As far as I know, SWA added FOQA in 2018, too late for this accident. But since 2018, there have several instances of unstable approaches that were not aborted before getting too close to the ground. (Most notably, on March 23, 2024, when SWA Flight 147’s “Near Collision With Tower” – see https://youtu.be/xauO-7FH8qI?si=TB_Ptth5wpvlnlpW (VAS Aviation).

- Avoidance lists which place pilots on “no fly” lists should be eliminated. These lists serve to isolate some pilots from problem pilots, allowing those problem pilots to continue undetected. Airlines should encourage lower tier management levels to hear and handle pilot complaints that reduce the consequences of such reports but allow grievances to be addressed before they get worse.

9

Sidebar: Was Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) a factor?

I am sure DEI was an issue for this captain, but I’m not sure it was an issue used against her as she imagined. I think it is remarkable that she was hired in the first place, given her low experience level. But to her credit, she passed all initial and continuing training. I would think that should have told her DEI was not a negative factor, at least in her case. If it became an issue with leadership, it might be, because she decided to make it an issue just three years after she was hired.

In 2003, as a relatively new first officer, she asked for a meeting with the Vice President of Operations to “talk about women in her department.” When she showed up for the meeting, the VP brought along four or five senior staff, including a woman from “the people department.” She made her case that SWA should hire more women. The VP said he was under no obligation to do so. “She agreed and left and believed she was then labeled for fighting for minority rights.” [Interview Summaries, p. 64]

Perhaps she was right. But I think it just as likely that the VP was simply annoyed by a relatively junior first officer presuming to tell him what to do. If he did say he was under no obligation to do so, I would agree he could have been more tactful. But I think she was overstepping her bounds as an employee to ask for the meeting in the first place.

I believe SWA could have done a better job training this pilot with no crew experience to become a better first officer and then a better captain. But I agree with the NTSB that she was the primary cause of this accident. DEI may have played a role in that her male supervisors may have been reluctant to counsel her with the same frankness they would have given a male pilot.

Did flying as a captain change her opinions? I’ll leave you with more quotes from her NTSB interview.

Culturally it was known on the line, if a pilot did what flight ops wants them to do or say they would protect you and support you. There were numerous male pilots involved in incidents and accidents and involved in sexual harassment cases, but she knew when she was in the chief pilot’s office that she did not have that support or protection.

Regarding something that could have prevented the accident from occurring, she thought the big issue was the culture. She did not think the line pilots were against having the culture changed but there was no leadership to support the change. She hesitated in the cockpit and she wondered if the FO was going to turn her in to her chief pilot. That threat would be in her mind until she could figure out who her FO was. She felt that the accident FO was quiet and unresponsive and pilots like that were the result of confusion over rumors and not retaliation against her. As an assertive female captain, “I'm the b word”. An assertive male captain was a “good captain.” They needed to get away from that.

Regarding her use of the term retaliation, she was asked how she felt she was retaliated against. She said the big thing was the avoidance bid list and being turned into her CP. While issues would be addressed in the cockpit, no FO told her that they were going to the CP. That was all done behind her back. She tried to find out why the pilots did not go to professional standards. Her opinion was that pilots did not go to professional standards because they were not interested in changing themselves or the situation but they were interested in hurting her.

Interview Summaries, pp. 66 - 69

References

(Source material)

Aviation Investigation Final Report, DCA13FA131, July 22, 2013, Boeing 737, Hard Landing

Boeing Performance Analysis – Southwest 737-700 N753SW Nose Landing Gear Collapse on Landing, La Guardia, New York, 22 July 2013, letter dated 06 February 2014

Cockpit Voice Recorder, Group Chairman’s Factual Report, DCA13FA131, dated August 16, 2013

Flight Data Recorder, Specialist’s Factual Report, DCA13FA131, dated October 27, 2014

Human Performance, Group Chairman’s Factual Report, DCA13FA131, Dated September 5, 2014

Interview Summaries, Aviation Investigation Final Report, DCA13FA131, Attachment 1

Kruger, Justin; Dunning, David. "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1999

Operational Factors, Group Chairman’s Factual Report, DCA13FA131, dated July 23, 2014