There is a prime directive for all pilots, especially instrument pilots: you can never assume the aircraft's attitude will take care of itself. Even in fly-by-wire aircraft that promise to maintain a vector, there comes a point where the aircraft's flight path can surprise you. When you get into the world of heavy aircraft, things get more complicated because of an apparent contradiction. The aircraft's inertia can make things seem to happen in slow motion; but the resulting momentum can make it seem things are getting out of control very quickly.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-08-01

There is a tremendous amount of speculation about the near-loss of a United Airlines Boeing 777, which plunged out of the sky minutes after takeoff. The crew saved it just over 700 feet above the ocean, pulling nearly 3 Gs in the pull up. There were no injuries (everyone was seated) and the aircraft was not damaged. None of this was reported to ATC. So the crew continued their flight from Maui to San Francisco. They reported the incident in company channels and the entire episode was about to be forgotten. Two months later the incident became public due to the excellent work of The Air Current

I think the NTSB dropped the ball on this one. Yes, they didn't have a lot to work with because they didn't have the Flight Data or Cockpit Voice recordings, which were long erased by the time they got involved. But they either failed to ask the right questions or simply agreed to let United cover this up. There is a lot to learn from this near catastrophe.

1

Accident report

- Date: 18 December 2022

- Time: 14:51

- Type: Boeing 777-222

- Operator: United Airlines

- Registration: N212UA

- Fatalities: 0 of 10 crew, 0 of 271 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: No damage

- Phase: Initial climb

- Airport: (Departure) Kahului Airport, HI (PHOG)

- Airport: (Destination) San Francisco, CA (KSFO)

2

Narrative

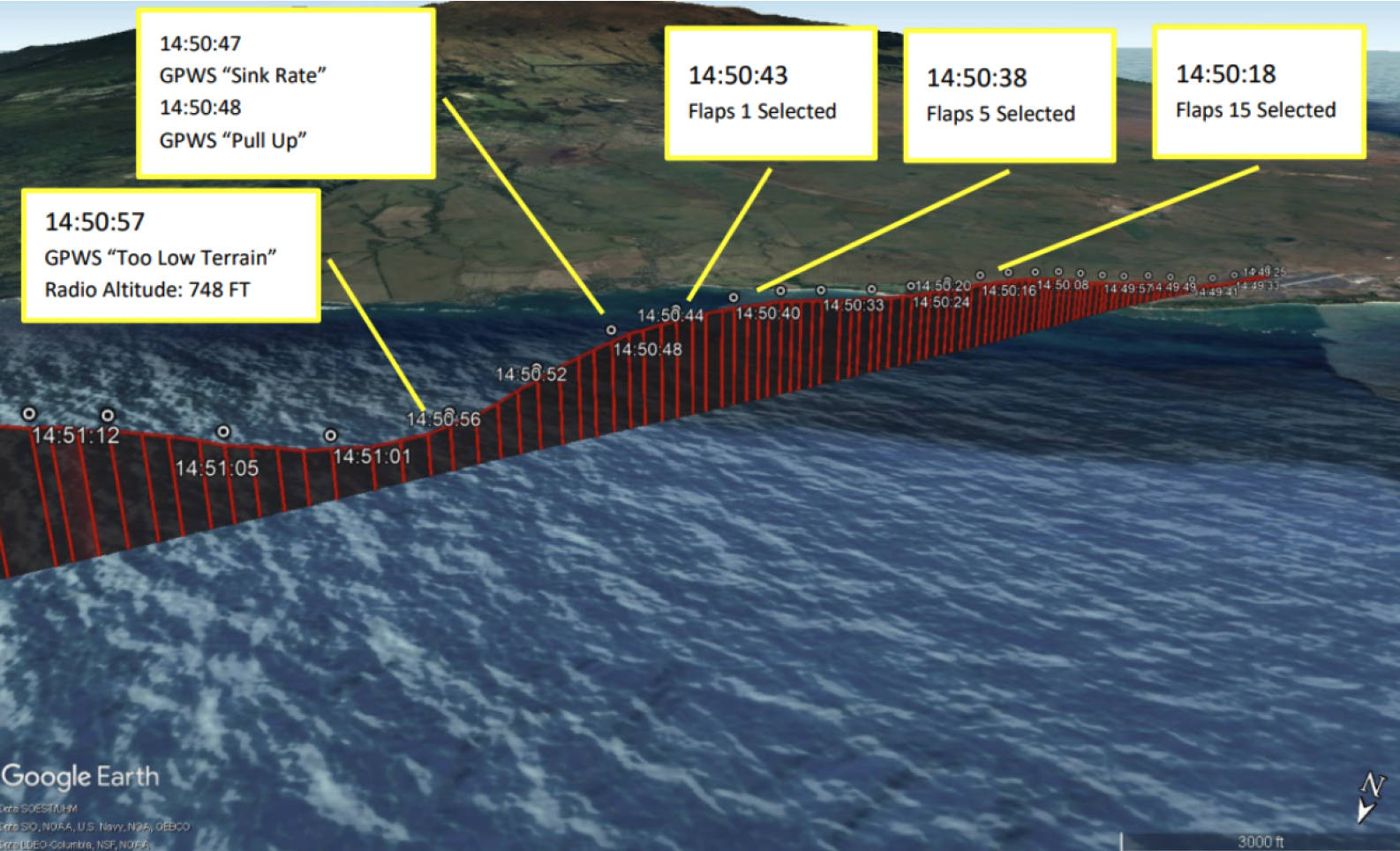

Flight track, NTSB DCA23LA172, fig 1

United flight 1722 lost altitude about 1 minute after departure while in instrument meteorological conditions, which included heavy rain. The airplane descended from 2,100 ft to about 748 ft above the water before the crew recovered from the descent. No injuries were reported, and the airplane was not damaged. The NTSB was not originally notified of the event, since it did not meet the requirements of Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations Part 830.5. However, the NTSB learned of the event about 2 months later and chose to open an investigation. By that time, both the cockpit voice and flight data recorder durations had been exceeded. The investigation utilized flight crew statements and other records as information sources.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 1

I was surprised when I first read this, but it is true. Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations Part 830.5 does not require pilots to report losing control of their aircraft. You might object to my use of the LOC term, but the pilot clearly didn't intend for the airplane to plunge downward at over 8,000 feet per minute just minutes after takeoff. Ergo, he was not in control of the aircraft.

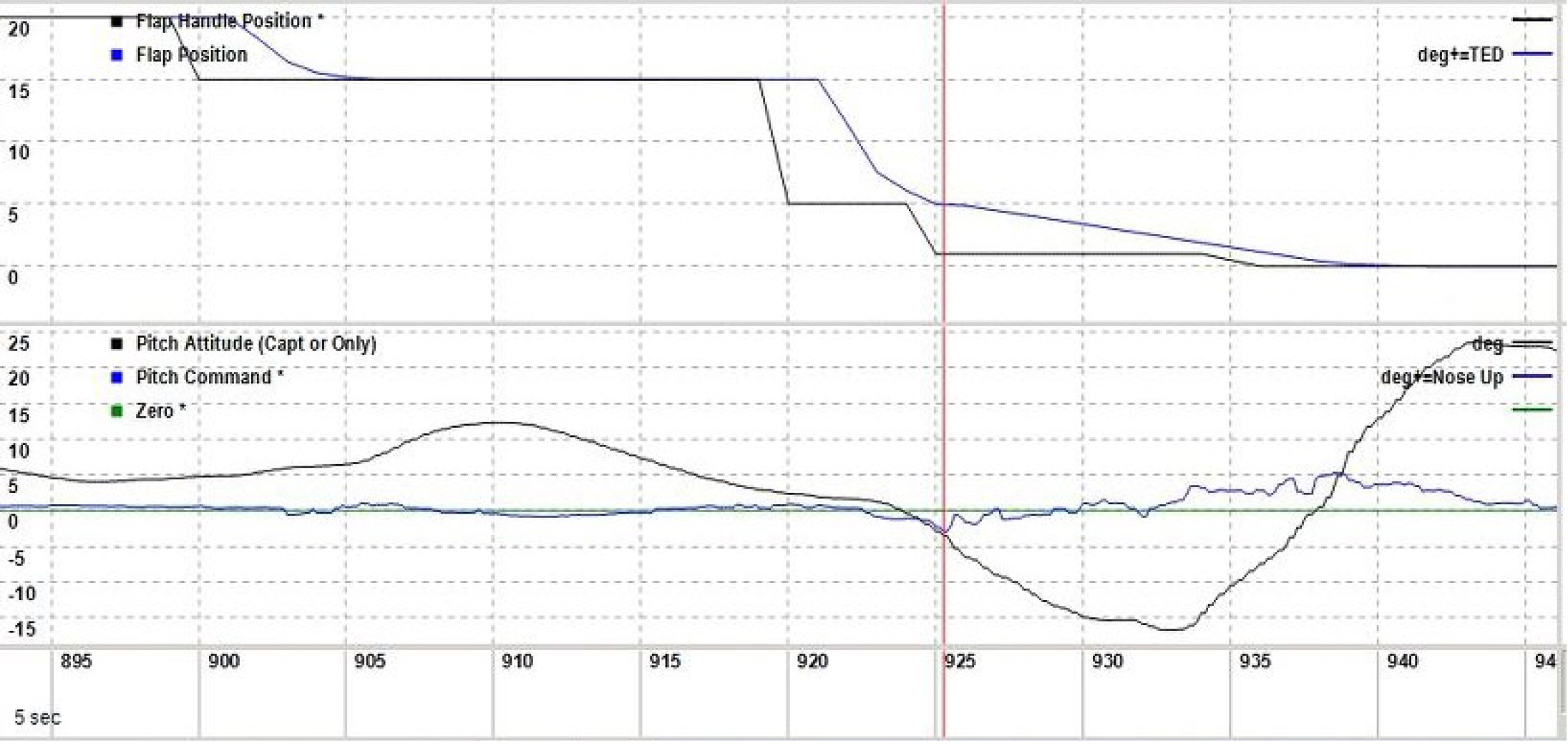

The captain (who was the pilot flying) reported that he and the first officer had initially planned for a flaps-20 takeoff (flap setting of 20°) with a reduced-thrust setting, based on performance calculations. However, during taxi, the ground controller advised them that low-level windshear advisories were in effect. Based on this information, the captain chose a flaps-20 maximum thrust takeoff instead. He hand-flew the takeoff, with the auto throttles engaged. During the takeoff, the rotation and initial climb were normal; however, as the airplane continued to climb, the flight crew noted airspeed fluctuations as the airplane encountered turbulence. When the airplane reached the acceleration altitude, the captain reduced the pitch attitude slightly and called for the flap setting to be reduced to flaps 5. According to the first officer, he thought that he heard the captain announce flaps 15, which the first officer selected before contacting the departure controller and discussing the weather conditions. The captain noticed that the maximum operating speed indicator moved to a lower value than expected, and the airspeed began to accelerate rapidly.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 1

Opinion: If confronted with a limiting flap speed in a climb without an altitude constraint, I think a proper reaction would be to increase pitch. This is especially true in a large aircraft with more weight than thrust. You should be reluctant to give up thrust right after takeoff.

The captain reduced the engine thrust manually, overriding the auto throttle servos, to avoid a flap overspeed and began to diagnose the flap condition. He noticed that the flap indicator was showing 15°, and he again called for flaps 5, and he confirmed that the first officer moved the flap handle to the 5° position.

The first officer stated that he “knew the captain was having difficulty with airspeed control”, and he queried the captain about it as he considered if his own (right side) instrumentation may have been in error. He did not receive an immediate response from the captain. Both pilots recalled that, about this time, the airplane’s pitch attitude was decreasing, and the airspeed was increasing. The first officer recalled that that the captain asked for flaps 1 soon after he had called for flaps 5, and when the first officer set the flaps to 1°, he then noticed the airspeed had increased further, and the control column moved forward.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, pp. 1 - 2

Opinion: When saying they "recalled" that the aircraft's pitch was decreasing and the airspeed was increasing, they demoted themselves from pilots to passengers. Their first reaction should have been to check aircraft attitude and thrust.

Both pilots recalled hearing the initial warnings from the ground proximity warning system (GPWS), and the first officer recalled announcing “pull up pull up” along with those initial GPWS warnings. The captain then pulled aft on the control column, initially reduced power to reduce airspeed, and then applied full power to “begin the full CFIT [controlled flight into terrain] recovery.” The first officer recalled that, as the captain was performing the recovery, the GPWS alerted again as the descent began to reverse trend; data showed this occurred about 748 ft above the water. After noting a positive rate of climb, the captain lowered the nose to resume a normal profile, ensured that the flaps and speed brakes were fully retracted, and engaged the autopilot. The remainder of the flight was uneventful.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172

As a result of the event, United Airlines modified one of their operations training modules to address this occurrence and issued an awareness campaign about flight path management at their training center.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 3

3

Analysis

Captain

Age 55, Male

19,600 hours (total, all aircraft); 5,000 hours (total, this make and model)

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 4

This is certainly a respectable amount of time in type. But was this recent time? The NTSB report and docket fail to look into this. One of my favorite aviation websites did a better job of investigating:

The captain, who was 55 years old, had over 19,600 hours total time and 5,000 of those were on the Boeing triple seven. That's a very respectable experience, but as my friend Juan Brown at the Blancolirio channel pointed out only 300 of those triple seven hours had been flown as captain. The final report doesn't clearly say this, but there is a possibility the captain might have operated on the Airbus A320 between his copilot triple seven experience and when he returned to it as a captain. That's often how it is done with the major airlines. If that was the case, well, then the captain was relatively new to the triple-seven left seat.

Extracts from: Mentour Pilot

He refers to Juan Browne at this YouTube channel: https://youtu.be/1B9mQQnZg_8?si=G-EoLd7iQ9awvCtW.

Captain's statement

Based on the winds showing only a slight crosswind, I elected to stay with FLAPS 20 and the reduced thrust setting. We briefed PWS [Protective Windshear System] and windshear precautions as well, and now RWY 02 was in use. During takeoff roll, I had my windshield wipers on high for the heavy rain. Acceleration was rapid, yet we had no non-normal airspeed fluctuations noted by the F/O. Rotation and initial climb were normal, but we soon began to encounter rapid airspeed fluctuations with light turbulence that became more moderate as we climbed. I noticed the aircraft reach thrust reduction and acceleration altitude (which were the same in this case) and I lowered the nose slightly to begin the acceleration. I called for FLAPS 5 and noticed VMO/MMO moved opposite to my expectation (towards the Speed Bug instead of a higher speed). Airspeed began to accelerate rapidly, and based on the rate of increase, I anticipated a Flap overspeed. I reduced the power manually (overriding the autothrottle servos), but not enough to incur a reversal in IVSI towards a descent. We were still a positive climb. The reduction in power was to reduce the extent of the Flap overspeed and slow the airspeed acceleration trend. We ended up over speeding the flaps by approximately 10-15 kts as I recall. My next course of action was to quickly find out the status of the flaps and if there was a mechanical failure. I glanced over to the Flap indicator and noticed the Flaps were at 15 instead of 5 as I had asked for. I would note that the selection of retracting the flaps from 20 to 5 is a normal and acceptable line operation procedure, and in my experience the most common, however, to the best of my knowledge there are no flight manual restrictions on retracting the flaps from 20 to 15. There were no EICAS messages or chimes noted at that time. I immediately called again for FLAPS 5 and repeated the call at least once more. I saw the F/O’s hand move towards the Flap handle and made the selection. There were no abrupt or excessive control inputs made at anytime, but I noticed the aircraft in an immediate and significant nose down attitude with a slight bank. Airspeed was rapidly rising, and I began to hear the EGPWS calls of “Terrain, Terrain, Pull Up”. As I began a pull on the control wheel to get the nose back above the horizon on the PFD, I initially reduced power to reduce airspeed acceleration. I quickly reversed into full power (to the stop) to begin the full CFIT recovery maneuver - taking care to make sure the speedbrakes were still stowed as well. Once I noticed the rapid change in IVSI towards a climb trend I lowered the nose towards the Flight Director commands to resume the normal profile. I don’t recall when the flaps were requested and moved to position 1, but I did call for the flaps to be completely retracted and the after takeoff checklist, shortly thereafter. The autopilot was soon engaged as well. We resumed the climb and were immediately faced with the expected threats of continued moderate turbulence and weather deviations in the climb to altitude.

Once we were safely established in the climb, I called the Purser to get a report on the condition of the passengers, crew, and aircraft status. He stated that everyone was ok and the aircraft was fine internally with no perceived damage. I elected to continue onward to SFO based on my best judgement and assessment of no aircraft damage overall, no internal damage, and no injuries to passengers or crewmembers reported. Once enroute, the F/O and I did a long and thorough debrief of the incident and he made notes of all pertinent factors and details to add to our FSAP reporting. We made specific note of the initial Flap selection, the resulting Flap overspeed, unusually extreme weather for the Hawaiian Islands in general, reports and possible encounter of LLWS, and conditions encountered shortly after takeoff. We sent a writeup and notes to TOMC enroute about the Flap overspeed. I continued constant contact with the Flight Attendants enroute to check on their condition and concerns, and that of the passengers as well. Nothing adverse was noted in the condition of aircraft, crew, and passengers throughout the flight. The remainder of the flight was uneventful and we arrived in SFO that night with no further incident. Before deplaning, we were met by a mechanic and briefed him on details of the aircraft condition and Flap overspeed.

Source: Pilot Statement (Captain)

I think the "FSAP" refers to the ASAP, Aviation Safety Action Program.

First Officer

Age (not given), Male

5,300 hours (total, all aircraft); 120 hours (total, this make and model)

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 4

The Pilot/Operator Aircraft Incident Report provided more information about the pilot. It says he had several type ratings: Boeing 757, 767, 777, Airbus A320, DC-9, CL-65, ERJ-170, 190. The time in "this make/model" was redacted. The official report says 120 hours.

First Officer's statement

Winds on Takeoff roll reported at 140/10 on Runway 02. Climbing through about 1,200ft, I heard the Captain announce “Flaps 15” as Maui Tower switched us to HCF Departure. I selected Flaps 15 and checked in with HCF Departure climbing through ≈ 1,400ft and into IMC. HCF responded “Climb and maintain 16,000 ft” and advised moderate to extreme precipitation all quadrants and any weather deviations were approved. I noticed our airspeed holding just below max Vfe, ≈ 178KTS, selected WXR on the EFIS Control Panel, and then adjusted the altitude in the altitude window on the MCP. At this point we were climbing through 2,000ft, and I noticed our pitch slowly decreasing, but still maintaining a positive pitch angle. The following happened within 10-15 seconds. The Captain announced “Flaps 5” and I heard “Don’t Sink” at the same time. The pitch angle decreased further towards a 00 pitch angle and our airspeed increased rapidly through the current Vfe limit.

At this point I knew the Captain was having difficulty with airspeed control and I noticed our pitch turn to a negative pitch angle. I queried the Captain on what was happening. I couldn’t be certain what the Captain was dealing with, since I saw no windshear indications and heard no immediate response from the Captain after my query. I wasn’t sure if there was an instrumentation error on my flight instrument displays and was confused about how he was responding to the increase in airspeed and the aircraft pitch attitude. Very shortly after calling “Flaps 5”, the Captain announced “Flaps 1”. I selected Flaps 1 and noticed our airspeed continue to increase as the yoke moved forward, pitching the nose down and the thrust stayed at a climb power setting with the Captain overriding the thrust levers slightly. I glanced over to cross-check the Captain’s PFD and his handling. Instantly after looking over, I sensed cloud movement out the forward window, indicating a cloud breakout. I instantly recognized the severity of our situation, looked down and noticed our airspeed 20-30 knots past the Vfe limit, with the altimeter falling, and the pitch around -8 degrees to -10 degrees nose down. I announced “Pull Up, Pull Up, Pull Up, Pull Up” many times as the GPWS annunciated. The Captain then brought the yoke aft, increasing our pitch angle, pulled the thrust to idle, then as the aircraft began a positive pitch trend, the Captain then increased thrust to maximum, and called “Flaps Up” performing an escape maneuver. In the same moment, I checked the speed brakes and heard “TERRAIN, TERRAIN, PULL UP, PULL UP” as our descent stopped and reversed trend around 800ft on the radar altimeter. Our pitch increased to over 20 degrees nose up and our airspeed trend reversed and then held at around 230kts as our Vfe limit went to the Flaps Up normal limit.

The Captain said he did pitch forward, but didn’t think he pitched forward enough to cause such a dramatic pitch change and concluded we must have hit windshear or a downdraft.

Source: Pilot Statement (First Officer)

Weather at the airport

IMC, Day, Visibility 3 miles, Lowest Ceiling Broken 900 ft., Precipitation Heavy Rain

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 5

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this incident to be: The flight crew’s failure to manage the airplane’s vertical flightpath, airspeed, and pitch attitude following a miscommunication about the captain’s desired flap setting during the initial climb.

Source: NTSB DCA23LA172, p. 3

This isn't the cause, this is what happened. To find the cause, you have to ask the question "Why?"

5

Commentary

Speculation problem: we just don't have the data

In 2021, Scott Kirby, the CEO at United Airlines made news during an interview with Axios on HBO. Kirby said the company was committed to ensuring 50% of their graduating pilot classes would be women or people of color. I've seen speculation that the reason the names of the pilots flying United 1722 have not been released is because one or both may have been a DEI hire. I won't add to that speculation but will lament that United was not more forthcoming to dispel this speculation.

Fly-by-wire philosophies: beside the point

There has also been speculation that the captain spent most of his recent experience in the Airbus A320 which has a different fly-by-wire philosophy than the Boeing 777. That is probably true and a valid point. I believe the A320 would have self-trimmed and not have been pitch sensitive to thrust changes or flap movement. The 777 would require pitch adjustments to large movements of the throttles. But I think this is beside the point.

I've flown three types of fly-by-wire aircraft, one of which was "path stable." I flew with a test pilot who claimed the aircraft would maintain its path, vertically and horizontally, with my hand off the stick. "No matter what," he said. "What if I run it out of airspeed?" Well, okay. "What if a windshear is stronger than the aircraft's pitch authority?" Okay.

In my view, no matter the flight control philosophy, it is the pilot's responsibility to monitor attitude and path. If they are not what you intend, it is up to you to fix it.

Flight data, NTSB MFR

Thrust and configuration changes on pitch feel

I've flown several Boeings and while some are impacted more than others, having engines under the wings tends to create pitch up moment when adding thrust and pitch down when reducing thrust. I don't recall a large pitch change when flaps are retracted, but I am told that is a factor on some Boeings.

The impact of somatogravic illusion

The crew of UAL 1722 was using full thrust while flying de-rated thrust V-speeds. This practice is allowed by UAL because it is thought to be a conservative approach. The problem is this induces a "somatogravic illusion" of a pitch up when accelerating. So the pilot's sense of pitch up and down had been jarred during takeoff. During the acceleration for flap retraction, the pilot may have had a sense of pitching up and may have subconsciously reduced the pitch as a result. More about this: Somatogravic Illusion.

The prime directive for all instrument pilots

The NTSB believes this incident was caused by the crew's failure to monitor the vertical flight path. That isn't what caused the incident, it is the incident. The real cause, I believe, was the pilot failed to monitor the aircraft's attitude and allowed it to fall well below level flight before taking corrective action. If keeping the attitude precisely under control is all you can do, that is all you should do. You can use the copilot to do the trouble shooting, have the copilot fly while you troubleshoot, or give it to the autopilot.

References

(Source material)

Aviation Investigation Final Report, United Airlines 1722, Incident Number DCA23LA172, December 18, 2022.

Memorandum For Record, NTSB DCA23LA172, March 8, 2023.

Pilot statement (Captain), NTSB Docket, DCA23LA172.

"Seconds from IMPACT! United Airlines Flight 1722," Mentour Pilot, https://youtu.be/_CloLeo-esQ?si=Zil8gfZPubpvrTyL.

"United dive afer Maui departure adds to list of industry close calls," Jon Ostrower, The Air Current, February 12, 2023.