The NTSB gets this mostly right: an inexperienced captain with weak instrument skills flies an unstable approach requiring he reduce his power to idle while on glide slope, fails to notice his speed, and then suspects the first officer did something to cause the stick shaker to go off. When he finally recognized the need for a stall recovery, he pulls back on the yoke and applies less than full power. The NTSB, however, failed to recognize the industry-wide problem of pilots trained to fight for altitude rather than the imperative to break the stall.

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-03-14

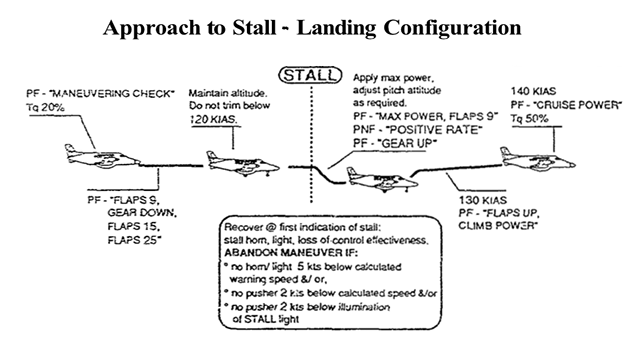

J-4101 approach to stall,

NTSB AAR-94/07, Figure 1.

But there is one more factor that I think everyone has missed. The captain was known to rely on the autopilot when flying in actual instrument conditions indicating he may have had a weak instrument crosscheck. He arrived at the glide slope too fast and pulled his engines to flight idle and did not notice his speed falling below his target approach speed. When the stick shaker went off and the autopilot disengaged his brain may have been in a panic and reverted to trying to trouble shoot the autopilot and stick shaker rather than accept the airplane was in a stall. More about this: Panic.

1

Accident report

- Date: 7 January 1994

- Time: 21:21

- Type: British Aerospace 4101 Jetstream 41

- Operator: Atlantic Coast Airlines operating for United Express

- Registration: N304UE

- Fatalities: 3 of 3 crew, 2 of 6 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airport: (Departure) Washington-Dulles International Airport, VA (IAD/KIAD) United States of America

- Airport: (Destination) Columbus-Port Columbus International Airport, OH (CMH/KCMH), United States of America

2

Narrative

- At 2316:28, flight 291 was advised of their position, 10 miles from SUMIE, to maintain 3,000 until established on the localizer, and was cleared for the ILS approach to runway 28L at CMH. The flight crew acknowledged the clearance. About 1 minute later, air traffic control (ATC) instructed flight 291 to reduce its speed to 170 knots and to contact the CMH tower controller.

- At 2317:58, sounds similar to a reduction in propeller/engine noise amplitude is noted on the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) transcript.

- At 2318:20, the crew contacted the CMH local tower controller. The controller cleared flight 291 to land on runway 28L. The last transmission to ATC received from the airplane before the accident was the acknowledgment of that clearance.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶1.1.

- 2320:39.8 CAM [sound similar to increase in prop/engine rpm]

- 2320:4 1.1 INT-1 "three."

- 2320:41.6 INT-2 "yaw damper."

- 2320:42.7 INT-1 "and autopilot to go .. don't touch."

- 2320:44.5 INT-2 "don't touch"

- 2320:46.2 INT-2 "holding on the yaw damper"

- 2320:46.6 CAM [sound similar to that 01 stick shaker starts]

- 2320:47.2 CAM [sound of seven tones similar to that of autopilot disconnect alert]

- 2320:40.1 INT-1 "tony."

- 2320:49.5 CAM [sound similar to that of stick shaker stops]

- 2320:50.2 INT-1 "what did you do?"

- 2320:50.8 INT-2 "I didn't do nothing.

- 2320:51.0 CAM [sound similar to that of stick shaker starts]

- 2320:52.3 CAM [sound similar to increase in prop/engine noise amplitude]

- 2320:52.5 INT-1 "gimme flaps up."

- 2320:52.5 CAM [sound similar to that of stick shaker stops]

- 2320:53.7 INT-1 "no no hold it."

- 2320:54.0 GPWS "pull."

- 2320:54.3 CAM [sound similar to that of stick shaker starts and continues to end of recording]

- 2320:55.3 INT-1 "gimme flaps up."

- 232057.5 CAM [sound similar to that of change in or addition to stick shaker]

- 232058.7 INT-1 "whoa."

- 2321:00.2 CAM [sound of impact]

- 2321:00.8 CAM [End of Recording]

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, pages 100 - 102] Cockpit voice recorder transcript

3

Analysis

- The captain's RTC J-4101 instructors described him as an average student. After completing 13.2 hours in J-4101 upgrade/transition training, which was his first exposure to a "glass cockpit" type aircraft, the captain failed his initial J-4101 type rating check ride on September 30, 1993, because of difficulties with instrument approaches, emergency procedures, and judgement.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶1.5

One of the pilots he had flown with noted the captain tended to rely on the autopilot for instrument approaches. Prior to the mishap, most (if not all) of his approaches in this airplane were in visual conditions.

- The first officer had not previously been employed as an air carrier pilot. He had been hired by ACA as a first officer 3 months before the accident. He had completed J-4101 second-in-command (SIC) ground school and flight training administered by RTC one month prior to the accident.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶1.5

- At 2320102, engine torque values decreased from a previously steady value of 25 percent to between 6 and 11 percent, while the propeller rpm values remained steady at 97 percent. The airspeed was 174 knots and decreasing. The flaps began to move from the full-up position 4 seconds later, reaching 15° at 232025.

- At 2320:28, the torque reduced to nearly "0" as the propeller rpm values increased to 100 percent. The airspeed had decreased to 125 knots, and the radio altitude was 525 feet. The airplane was on the localizer and G/S. The angle of attack (AOA) and pitch values began to increase.

- At 2320:42, the airplane started to descend below glideslope I.7 miles from the runway at an airspeed of 115 knots. CVR and/or FDR data show that the landing gear were down, and wing flaps were at 15°. Further, the altitude was approximately 637 feet above runway elevation, and airspeed was 115 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS) at 2320:42.

- At 2320:45, the autopilot and yaw damper transitioned to "off" as the airspeed decreased to 104 knots, and the radio altitude indicated 410 feet. The G/S data indicated that the airplane was less than 1/2 dot low, as the AOA and pitch attitude values increased to 14.6° and 3.7°, respectively.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶1.16.1

It appears the captain's attention may have been centered on getting the autopilot back. The report speculates that his unfamiliarity with the glass cockpit instruments may have impacted his understanding that his airspeed was critically low.

- At 2320:46.6, the airplane was about 2/3 of a dot below glideslope when the stall warning system (stick shaker) activated. According to company procedures, the minimum ILS approach speed at this stage of the approach should have been 130 KIAS. The stick shaker activated at 104.5 KIA3 and remained on for 2.9 seconds, until 2320:49.5. The stick shaker activated for the second time at 2320:51.0, 101.5 KIAS, and 315 feet above the ground. FDR vane angle-of-attack (AOA) values exceeded the stick pusher activation threshold 0.4 of a second after the stick shaker activated. The FDR shows that engine torques began to rise above idle thrust at 232052.0, or 5.4 seconds after the stick shaker first activated. At 2320:54.9, FDR data show that the flap angle had started a steady decrease that reached 0° by ground impact. Vane AOA values repeatedly exceeded the stick shaker and stick pusher thresholds during the final descent, until the airplane crashed at 2321:90. The evidence indicates that pitch attitude and wing AOA were increasing and decreasing in response to nose-up and nose-down elevator deflections, respectively.

- During the remaining 15 seconds of recorded data, the airplane entered a series of pitch and roll oscillations, the power was increased and the flaps were raised. The peak vertical acceleration recorded during this period was 1.52 "G," and lowest and highest airspeeds were 99.4 and 124 knots, respectively. The peak torque value was 84 percent recorded for the right engine 2 seconds before the end of data. The end of data was recorded at 2321:01, as the pitch attitude indicated 22° nose up, and roll attitude indicated 1.4° right wing down.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶1.16.1

- The evidence indicates that the captain of flight 291 followed company procedures until the point at which he initiated the ILS approach to runway 28L at CMH. However, he did not slow the airplane in sufficient time to be able to configure the airplane in a timely manner. After reducing power to flight idle to slow to approach speed, the pilots failed to monitor airspeed, and the captain failed to add power as the airspeed approached 130 knots. The airspeed decreased through the minimum of 130 knots for the approach until the stick shaker activated because the airplane was approaching stall speed.

- The autopilot repeatedly trimmed the airplane nose up to stay on the ILS glideslope, which, in conjunction with the low thrust, caused the airspeed to decay well below the minimum approach speed of 130 knots. The CVR indicates that less than 4 seconds after the captain stated, "and autopilot to go ...don't touch," the sound of the stick shaker began, followed by the tone for the autopilot disconnect. The airplane decelerated to 104 knots, which was 26 knots below the minimum approach airspeed specified by airline procedures, at which point the stick shaker activated for 3.1 seconds. Immediately after the stick shaker warning, the autopilot disconnected, and the airplane started to pitch down at approximately 3 degrees per second. Warning tones (presumably from the autopilot disconnect) started about 0.6 of a second after stick shaker. There was no dialogue heard on the CVR until the stick shaker deactivated.

- The evidence suggests that the captain was distracted by these events and that he attempted to determine what the first officer had done to cause the stick shaker to activate and/or the autopilot to disconnect. During that short interval, when the captain was trying to determine what had happened, the stick shaker was silent. There was no indication on the CVR or FDR that the captain was aware of the extremely low airspeed and impending stall because he did not begin the proper stall recovery procedure. The captain asked the first officer, "what did you do?" The first officer responded, "didn't do nothing." Commensurate with the first actuation of the stick pusher, the power was partially applied to the engines.

- FDR data indicate that the captain applied nose-up elevator without adding power. The airplane pitched up in response to the nose-up elevator command, but the airspeed was too low to arrest the descent rate, and the AOA increased to the point that the stick pusher activated. The stick pusher quickly moved the elevator nose down, which caused the airplane to pitch down, preventing a stall. However, FDR data indicate that the captain fought the stick pusher with large aft (nose-up elevator) control column inputs.

- Engine power did not rise above idle until 5 seconds after stick shaker activation and .l6 seconds after the stick pusher activated. It then increased only about one-half as fast as would be expected from a full throttle application.

- In contrast to the approved procedure, about 1 second after stick pusher activation, the captain called for "flaps up." The investigation revealed no procedure in either the J-3201 or the J-4101 in which stall recoveries or go-around procedures would require a flaps-up response.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶2.1

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause of this accident to be:

- An aerodynamic stall that occurred when the flight crew allowed the airspeed to decay to stall speed following a very poorly planned and executed approach characterized by an absence of procedural discipline;

- Improper pilot response to the stall warning, including failure to advance the power levers to maximum, and inappropriately raising the flaps;

- Flight crew inexperience in "glass cockpit" automated aircraft, aircraft type, and in seat position, a situation exacerbated by a side letter agreement between the company and its pilots; and

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶3.2

The agreement locked more senior pilots into other aircraft for a minimum period before they could change aircraft, providing opportunity for more junior pilots to fill the captain and first officer positions in the J-4101.

- The company's failure to provide adequate stabilized approach criteria, and the FAA's failure to require such criteria.

- The company's failure to provide adequate crew resource management training, and the FAA's failure to require such training; and

- The unavailability of suitable training simulators that precluded fully effective flight crew training.

Source: NTSB AAR-94/07, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-94/07, Stall and Loss of Control on Final Approach, Atlantic Coast Airlines, Inc. / United Express Flight 6291 Jetstream 4101, N204UE Columbus, Ohio January 7, 1994