As we’ve seen in our previous chapters, it is vitally important that we learn to place all that we do in aviation into a compartment that can be somehow isolated from the rest of our life and that social pressures deserve special attention in this effort.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-02-01

There is another aspect in all our lives that also requires special attention, and that is the competition for our attention that comes from family issues. Your family can provide a solid foundation from which all other aspects of your living benefit, or family problems can detract from everything else you do. It is to every aviator’s advantage to make sure the “family compartment” supports the aviator compartment so that your focus on aviation is complete when it needs to be.

1 — Getting your family’s support

1

Getting your family’s support

We often dismiss the risks of our occupation to put our families at ease and that is in many ways the right thing to do. Or is it? You may also modestly believe that flying airplanes is no more dangerous than many other occupations and the risks are certainly no greater than being a firefighter or police officer. We certainly deal with life and death situations, but no more than does a doctor or other medical professional. But there are key differences. Not many occupations require complete focus from their practitioners in such fluid environments. It is the classic “hours of boredom interrupted by minutes of terror” syndrome. When things go wrong, or even when they go right, we are required to come up with the right answer in an instant. We don’t have the luxury of calling time out or withdrawing until we can get help. That is why our hours of study and our demands for quiet during rest periods are critical. If your family doesn’t understand this, your efforts at building an aviation compartment will meet resistance.

2

Be honest about the risks

How do you get the family on the same team when it comes to allowing you the free space needed for your aviation compartment? And how do you do that without causing them undue stress? (Which can lead to pressure from them for you to find another way to earn a living.) Perhaps a quick story is in order.

The Air Force has made great strides over the years to improve the safety of flight training and when I went to Undergraduate Pilot Training (UPT) in 1979, things were better than they had been but not as good as they are today. That year the Air Force lost four of their Cessna T-37B primary jet trainers and four of their advanced Northrop T-38A advanced jet trainers. We had four deaths at my base that year, the first occurring just before I started flight training. I never brought that or the next two deaths up to my wife and she never mentioned them until our next-door neighbor was the fourth to perish. We talked about it briefly but didn’t dwell on it. A few years later, when I was flying the Boeing KC-135A tanker, she asked me about a recent crash at our base. The KC-135 had averaged between two and three losses a year up to that point in its history. I explained that most of the crashes were due to pilot error and that her pilot spent a lot of time trying to avoid those kinds of errors. She accepted that and I assumed nothing more needed to be said about it. After I left the Air Force, I overheard a conversation she had about my twenty years as an Air Force pilot and all the deaths. “Of course, I was worried sick,” she said, “but what could I do about it? I just had to trust that he knew what he was doing. I’m just so happy that part of his flying is over.”

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the United States Air Force has gotten its act together in the way it trains pilots and losing eight training aircraft in a single year these days would grind the entire operation to a halt. They don’t accept these losses as a normal cost of operating anymore. But it does beg the question, how do you let the family know this isn’t just a normal office job while assuring them that you are taking all the necessary precautions?

First, be honest about the risks. While the accident rate in commercial aviation has fallen over recent years, it isn’t perfect. Moreover, the rate in general aviation is still much higher. Explain that a vast majority of these crashes were caused by pilots who were not sufficiently trained, rested, or serious about their profession. That is why you work so hard at training, getting proper rest, and studying.

Second, discuss any recent and notable crashes that may cause them concern or can help illustrate why the aviation compartment deserves the space you give it. As a Gulfstream pilot, I pay special attention to crashes that involve any Gulfstreams. On May 31, 2014, a Gulfstream GIV crashed at the end of the runway at Hanscom Field, Bedford, Massachusetts (KBED), when the pilots failed to disengage their gust lock, failed to complete a flight control check, failed to run any checklists, and failed to properly execute a takeoff abort. There were a lot of failures involved and all of them could be traced to the pilots. As the investigation unfolded, I explained to my wife where the GIV and the G450 I was flying at the time were similar, and where safety improvements had been made. I also explained how these pilots didn’t understand their aircraft systems as well as I did, and how they didn’t place the same importance on standard operating procedures that I do. She asked, “Why would any pilot be so reckless?” I answered that this kind of seriousness requires hard work and time. It requires a solid aviation compartment.

3

Be honest about your struggles to keep up

After several years of accident-free flying, passed check rides, and yet another type rating, your family may normalize the fact you defy gravity for a living and that you have it all mastered. Modesty is a fine trait, and your family probably admires the humility you display even while doing something everyone else considers one step removed from magic. It may not hurt to reveal what goes on behind the curtain now and then.

In 1986 the Air Force decided I needed to be a Boeing 747 captain so I was sent to United Airlines with instructions to earn an Airline Transport Pilot certificate with a 747 type rating. At the time I had a commercial license with a Boeing 707 and 720 type rating. How hard could it be? I heard that the airplane check ride was easy, but you couldn’t experience that until you passed the simulator check, which was known for a high bust rate. Our last Air Force pilot failed the sim check because he couldn’t clear the obstacles departing Runway 28L at San Francisco International Airport, California (KSFO) following an engine failure at V1. My first attempts ended with simulated crash trucks and an actual “Unsat” on my grade reports. “Don’t worry, you’ll get it,” I was told. The simulated aircraft was at maximum gross weight and the conditions required a very gentle 3 degree per second rotation to a very precise angle. Rotate too quickly or too high and you stalled. Rotate too slowly or too low, you didn’t clear the hills just north of the airport.

With each failed training session, I became more and more frustrated. I was also consumed with studying for the four-hour oral exam. We were moving from Hawaii to the mainland and our plan was for me to go solo for the first two weeks and for my wife to join me for the last two weeks so we could enjoy the Denver area together. I started to think that was a mistake because I just didn’t have the time for anything but my studies. As the check ride neared it became apparent that I was under stress that she had never witnessed before so she finally asked. I admitted that the V1 cut could do me in. Her perfect pilot husband, she learned, was not so perfect.

With just one simulator session to go before the sim check, the pressure was on. The engineer in me took over and analyzed my previous failures. I wasn’t rotating too quickly or not quickly enough. My rotation angle was always on target. Always. So what was causing enough drag to prevent the jumbo jet from climbing as Boeing had intended? That’s when the light came on. My sloppy rudder technique was causing the rudder to hang out in the wind and that was robbing us of acceleration. On training simulator number last, I managed to be smooth while applying enough rudder pressure to keep the aircraft flying straight, even with an outboard engine failed. We cleared the mountains as the performance charts predicted. I repeated that for the simulator check and after the flight check was awarded the ATP with B-747 type.

Years later, for another type rating, I overheard my wife chase our children away from the study. “Give daddy his space,” she said. “His mind will be somewhere else for a while until he memorizes another airplane.” As it turned out, my struggles with her as a witness paid dividends beyond the new license and type rating. I believe my family understands the flight compartment has a special place in my life and, by the way I think families should operate, their lives as well. I owe them something in return.

4

Supporting your family

When you release the brakes and unleash the Jet-A into its burner cans to accelerate from zero to more than 100 miles per hour in a matter of seconds, what you are doing at that moment is paramount. If you make a mistake, nothing else matters. That’s why you have an aviation compartment. When you are sitting at your desk, studying aircraft abort procedures, and your son comes in and says, “Dad, I have a problem,” then where does that aviation compartment fit in the big scheme of things?

Maybe you need a dad or mom compartment too. A son compartment. A friend compartment. Any number of compartments. But no matter how many or few you have the need for, the compartments must have boundaries and you must be able to switch from one to another when the need arises. The aviation compartment is unique in that it has a switch where all other compartments are muted. But that switch is reserved for when in the aircraft only. That isn’t to say the aviation compartment takes priority. In fact, it doesn’t.

As we saw in the article, Compartmentalization and a Focus on Flight, you cannot hope to fully concentrate on your flight duties if you have troubles at home. You need to cordon off some of your time and effort to ensure the family’s needs are met. I’ve made a lot of mistakes in this area and hope I can help you avoid repeating them.

- When approaching a fork in the career road, include the family in the decision making process and make it clear they have a voice in the process. If, for example, you have a great opportunity that includes a large pay raise but also doubles your time away from home, the family deserves a vote. If the kids are in grade school and your influence as a dad is more important than as the financial provider, your decision may be easy. If, on the other hand, the kids are off to college and the extra income could pay the tuition bills, your decision may be different. In any case, include the family before deciding.

- Take paid time off and don't let it expire unused! You may not feel the need for the time off but not taking it tells the family you would rather work than spend time with them. Even if that isn't true, it can be subconsciously interpreted that way.

- When approached by a family member with a request, try to place all of your focus on them. Avoid situations where you listen (or pretend to listen) while doing something else. This applies when you are inside your aviation compartment while studying or even in your relaxation compartment while watching your favorite YouTube channel. Picture this: you are typing notes about a new aircraft system when your spouse comes in asking about [place your least favorite topic here]. In the past I would continue to type while assuring her, “I’m listening.” And she would keep talking. After a while I realized I wasn’t paying attention to my studies or to her. I made the decision to avoid all future “half conversations.” I then vowed to immediately stop all work, turn to face her, make eye contact, and listen. I think she appreciated this and after she was satisfied, she would say, “thank you, please get back to what you were doing.” That was years ago. Now I notice she is careful to check on what I am doing before interrupting. I need to learn to pay her the same respect when she is absorbed watching her favorite football team.

- Learn how to live without checklists and how to be spontaneous for once in your life! As aviators, we appreciate that our minds can skip important steps and that a good checklist works for starting a jet engine, putting together a lasagna, or packing a suitcase for a family vacation. If a schedule gets the aircraft airborne on time, why not use a checklist for the next family vacation? When my children were unleashed on the driving public operating my cars, I was shocked that they didn’t appreciate the value of my car maintenance logs that recorded every drop of gas consumed since the day we bought them. I explained that a downward trend in fuel mileage was an excellent predictor of upcoming maintenance issues. They explained that it didn’t matter. (Good point, well made.) For your next family vacation, try giving up all planning and scheduling. Set a budget and see what happens. You might be surprised how much fun you have.

- Switch off the ice water in your veins and let the family know you are human. If you make it a habit to always display the “cool, calm, and collected” persona that your passengers value so much, experiment with showing how much you care about things important to the family. Years ago, a pilot in one of my Air Force squadrons was at a loss to explain his families anger following the death of their cat. He came home, found the dead cat, and chucked it into the dumpster. “It’s just a cat.” Even if you are in the “it’s just a cat” camp, understand you might be alone in this.

Wait a minute, you say. I’ve gone to great pains to say your aviation compartment is sacred and should not be violated. When on an ILS, you cannot allow stray thoughts about the cat or anything else outside the compartment dull your focus. But now I am saying you need to worry about the cat. What gives?

5

Understanding your limits

You have an aviation compartment that you can switch on and off when not actively aviating but can never be switched off while aviating. But what if you find that you cannot do that. One day you are a poster child of compartmentalization, the next something happens that makes any attempts at singular focus impossible. What then?

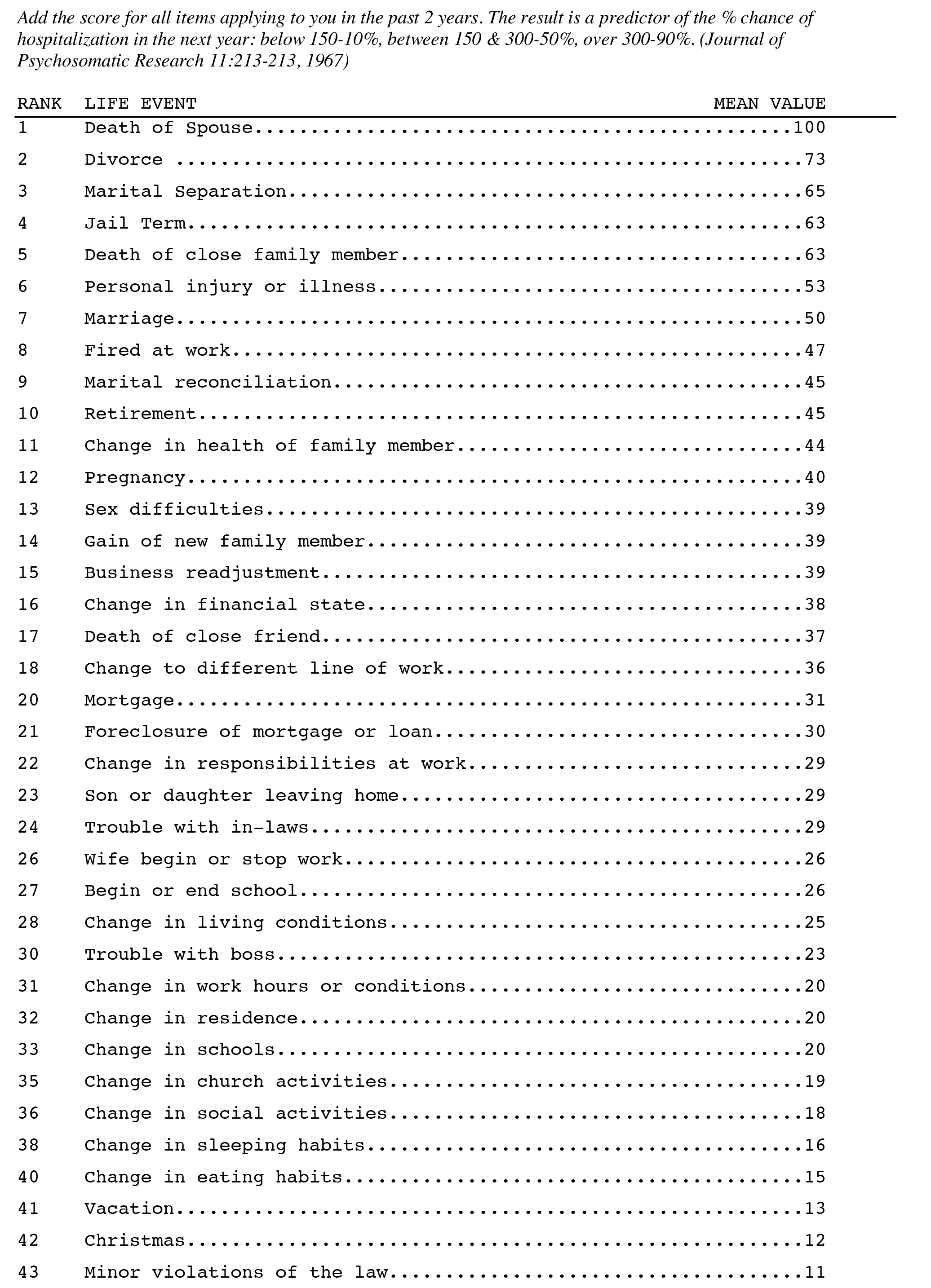

There are times when it becomes impossible not to be consumed by a factor outside your aviation compartment. We call these stressors because they place a stress on you that may or may not be debilitating. It could also be that you can easily handle one stressor but after another and another you exceed your limits. As an Air Force commander in my past or a flight department manager in my present, there are some situations where I will remove a crewmember from flight duties even if they insist they are okay. See the list of stressors for some examples. Let’s say you experience the death of a spouse. Off flight status, no doubt about it. But what about trouble with the in-laws? Or the foreclosure of the mortgage on your house? No? What about both? The situations vary and your ability to deal with the situations vary. There are two things you need to realize. First, feeling stressed is perfectly normal. Second, there may be a time when it is also perfectly normal to say, “I am too stressed to fly.”

Sometimes you need to retreat from a situation before it becomes hazardous, what we called the “Knock it off” call. If family demands become too great to handle your flight responsibilities, it may be that your family compartment crowds out the aviation compartment. It may be tempting to withdraw from the family, reasoning that the aviation compartment deals with life and death. Besides, the aviation compartment pays for the family compartment! But if your distraction leads to the end of the aviation compartment, what good did that withdrawal do?

We are not alone in this need to “knock it off” when faced with family troubles. In 2011, a tugboat pilot crashed a barge he was pushing into a tourist boat, killing two tourists, and plunging 35 others into the Delaware River. While on duty, he made or received 21 calls on his personal cell phone about a life-threatening medical emergency involving his son.

Even if not presented with such a distraction in the moment, having a family issue weighing on you can lead to equally dire results. There are times the family compartment trumps all others and when that happens, an aviator’s prime responsibility is to call knock it off. If you are flying, fess up, give the airplane to the other pilot if you have one, or land if you don't. If you aren't flying, stop whatever act of aviation is going on, and deal with the family first.