There is a continuum of pilot types that ranges from laid-back to hyper-wound-up and everything in between. No matter the pilot type, most of these profess to not care about outside criticism because they've compartmentalized feelings outside of the space reserved for all things aviation. We are cool, dispassionate, and have ice water running in our veins. All that is great. But it isn't true. Pilots are ego driven and that means we do actually care about what is said about us.

— James Albright

"Illegitimi non carborundum"

"Don't let the bastards get you down." Attributed to British army intelligence during World War II, adopted by US Army General "Vinegar" Joe Stilwell. Said to be Latin, but it doesn't actually translate into anything.

Updated:

2016-08-30

Okay, so let's say you deny that. So let's put it this way. You are an exception, but everyone else is affected. That means you need to be careful about the way you deliver your critiques and other criticisms to your fellow pilots. This is a fundamental skill of leadership, whether you are leading a large airline or a two-pilot crew. The fallout from doing this wrong can impact safety of flight.

Mistakes are a natural part of learning, even in aviation. The problem in aviation, however, is we start our flying careers learning from pilots who started just before us. Young, inexperienced instructors don't have the best bedside manner and instruction often degrades into name calling. Even in the Air Force. Or perhaps I should say especially in the Air Force. There is a better way.

When we are learning, we often know we've made a mistake but not how to correct it. Being critiqued angrily only shuts down the learning process. It seems like a little thing, but framing the criticism in a positive" and not a "negative" light can get the message across more effectively.

Once you've made your point, you need to "let it go" and not "harp on it." The other pilot did not set out to make a mistake, once you've made your point going on is just pouring salt on the wound. In the extreme, the pilot bearing the grudge can transfer that grudge to future encounters and end up ruining more than just one relationship.

If flying were easy, anyone could do it. Just because it was you that noticed the other pilot's mistake, that doesn't mean you haven't made the same mistake before or could possibly make the same mistake in the future. Addressing it as a we" and not a "he" or "she" problem can make it easier for the other pilot to receive the critique more receptively.

What if the person you are critiquing didn't understand the critique or, worse, appears not to understand the problem? You need to find a new angle" and not "repeat yourself." Repeating yourself will just make the other person feel you are picking on them. You need to re-articulate the criticism.

What if it is you that is on the receiving end? Your first reaction may be to return fire, "Oh yeah, what about . . ." This can be a real character test, but you need to "de-escalate" and not "escalate." If you come back with a counter-accusation you may end up with a counter-counter-accusation. Where will it end?

1 — The "what's wrong" not "who's wrong" technique.

2 — The "positive" and not a "negative" technique

3 — The "let it go" and not "harp on it" technique

4 — The "we" and not "he" or "she" technique

5 — The "find a new angle" and not "repeat yourself" technique

1

The "what's wrong" not "who's wrong" technique.

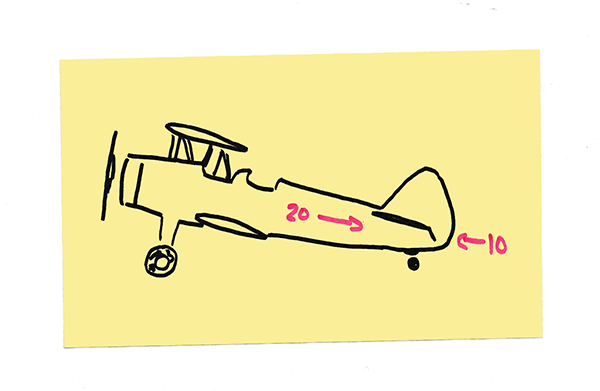

When I was in USAF pilot training we were told the supersonic T-38 would pose several challenges for most of us, not the least of which would be just getting it onto the ground. But once we mastered that, we were told, everything else would be relatively easy. Not so, for me. While I could maintain the airplane in perfect fingertip formation while flying two-ship and when flying number two or number three in a four-ship, I just couldn't figure out the number four position. We could be fully inverted in the middle of a barrel roll or pulling heavy g's on the bottom of a loop, I was in full control of the airplane as long as I wasn't number four. In that position, unless we were straight and level, I found myself over-controlling the airplane trying to keep on number three's wing. My instructor kept saying, "What's wrong with you? This should be easy! Why can't you do this?" To say the least, it was frustrating. I felt as if I was the only student in our flight having this trouble.

Four-ship fingertip formation, from ATCR 51-38, figure 7-20.

One day I was spared the aggravation of the number four position and got high marks as lead, number two, and number three. During one maneuver I noticed my number four wingman was having the same over-controlling issues. It was his first crack at four-ship, so that was to be expected. After the flight I eaves-dropped on his debrief. Here's what his instructor said: "The number four position is the hardest to master because you have to look through number three and keep relative position on lead, always making sure you have adequate spacing on three. If you focus on number three, of course you will end up all over the sky if number three isn't rock steady." It was an epiphany for me for two reasons. Technically, I didn't realize my focus should have been on lead and not number three. But from the point of view of criticism, I realized that I (the Who) wasn't the problem, it was the particular maneuver (the what) that was different. These realizations made all the difference. I got signed off in four-ship formation the very next flight.

2

The "positive" and not a "negative" technique

By 1981, the Strategic Air Command had been around for a while, 35 years, to be exact. The drill for a young second lieutenant copilot assigned to fly the B-52 bomber or KC-135 tanker was to learn quickly and become an aircraft commander. For the tanker copilot, that meant learning the airplane, how to fly the airplane, and how to pull "Emergency War Order" (EWO) alert. Alert was seven days of being tethered to an airplane, ready at a moments notice to run to the jet, takeoff, and fly to Russia. En route, we would offload every last drop of gas to a thirsty bomber which was primed and ready to end life on earth as we knew it. It was a surreal existences, especially for us copilots. Our fates were determined by the crew boss, known by his title, "Aircraft Commander."

KC-135A Alert Scramble, from Strategic Air Command and the Alert Program

A typical aircraft commander was a captain with between 1,500 and 3,000 hours total flying time, and somewhere between four and fourteen years of service in the Air Force. All of us copilots, in stark contrast, had less than those hours and years. For some of us, substantially less. You would expect the more experienced copilots would walk with a battle worn confidence, knowing they would soon upgrade to the left seat and join the ranks of aircraft commanders. And that was true with some of our senior copilots. But not all, as I found out one day mission planning as another crew returned from a flight.

"I'm sorry," Captain Chris Clark said as he followed his aircraft commander into the squadron ready room. "I guess with all the commotion I just sort of forgot."

"Yeah you sort of forgot, sluggo," Captain Wesley Haverstock said while loudly throwing his mission paperwork on the nearest table. "Let's go through today's laundry list and see how many new ways you found to screw up."

It was embarrassing to hear a fellow copilot berated publicly like that. But I couldn't leave because I had my own pre-mission paperwork to complete as they sorted through their post-mission stacks. Some of the things Chris was guilty of sounded awfully familiar, mistakes I had recently made. Of course Chris had been at it for several years, compared to my several months. But the tirade he was fielding could have easily been sent my way.

"Those wings on your chest say you are instrument rated," Haverstock said, "maybe we should give you half wings. We'll call you the fair weather copilot." With that, the two departed before I could decipher what the problem was. I was thankful my aircraft commander, Captain Rick Stiles, wasn't such a tyrant.

The next morning as we got our base operations briefing we learned that the base's ILS was out of service and all arrivals were expected to use an ASR approach.

"What's wrong with the PAR?" Rick asked.

"The vertical part of the system is out of service too," the briefer said. Those were pretty much the extent of our instrument approach procedure choices for our typically rotten weather. The ILS, Instrument Landing System, was the easiest to fly and the most likely to result in us popping out of the weather with the runway in front of us. The PAR, Precision Approach Radar, relied on a radar operator giving you lateral and vertical cues based his judgment issuing instructions and your skill following them. While not as easy, we tended to practice them to make them somewhat routine. The ASR, Approach Surveillance Radar, was a different matter entirely.

We were taught to fly the ASR in pilot training as a "dive and drive" which was fairly straight forward and gave you the luxury of concentrating on one thing at a time. You work the lateral the whole time while simply descending to the Minimum Descent Altitude. From there you were expected to see the runway. Not as reliable, but easy enough.

After our refueling we came back to the base with our typical winter forecast: low ceilings and visibility just around minimums. As predicted the only approach available was the ASR and I was set up to do that, just as I had several times in the T-37 and T-38, and maybe once or twice in the KC-135. As we neared the "start your descent" point, the radar controller said, "wheels should be down, start your descent." I pulled a handful of throttles.

"Whoa," Rick said. "Not so much."

"What?" I said.

"Remember you need to fly a glide path!" he said.

"On course," the controller said. "Your altitude should be one thousand, five hundred." We were three hundred feet low.

I then remembered the Strategic Air Command's variation on the ASR. We were not allowed to "dive and drive" on an ASR, but had to approximate a glide path based on the controller's suggestions.

"On course," the controller said. "Your altitude should be one thousand, two hundred." Still too low. The controller couldn't give us altitude corrections because his scope wasn't accurate enough. But he could see how far along the approach we were and how high we should be.

I played catch up for the rest of the approach, and as these things usually go, when you start out low you end up high. "On course, your altitude should be two hundred, take over visually." We were at 300 hundred but Rick spotted the runway and I landed. Well that's being kind. I forced the nose down in a wild hope that I could make the touchdown zone. I did, but I had to plant the airplane with a thud.

"Nice one, co," the navigator said. "I didn't need those fillings anyway."

As we returned to the squadron ready room Rick began his critique. "Nice job, James. Your heading control was excellent, I don't think we heard anything but 'on course' the entire time. And I think you were getting the hang of getting close to the altitudes. You probably ought to practice it on your next training flight."

And that was that. He signed my training forms and gathered the rest of the paperwork before leaving. I looked across the room to see Captain Chris Clark. "ASR?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," I said.

Wanna trade AC's?" he asked.

"No, sir," I said.

3

The "let it go" and not "harp on it" technique

I showed up to my Hawaii Boeing 707 squadron a first lieutenant, 25 years old, and in awe of the pilots who flew the airplane with such skill and ease. We had fourteen pilots, all but one of which seemed to have everything needed to be a great pilot and officer. The one exception was known simply as "Roy Boy."

Captain Roy Atwater appeared normal and seemed nominally competent in the cockpit. But there was something not right with him. "It all started when we got our first female in the squadron," I was told. "She was a radio operator and she messed up one of her position reports so badly the crew almost got violated. Roy Boy saw his career as an international pilot flash before his eyes and just snapped."

"He never let her forget it until she finally had enough and quit. Once she left the squadron, every other female that showed up got the same treatment. He's been counseled about it but it only got worse. Rumor is that's what caused his divorce."

All that happened before I showed up and my only contact with Roy Boy was once we heard we had a brand new female pilot scheduled to arrive. She would be our squadron's first female officer and the first female pilot anyone in the squadron, except me, had ever known. "No $#@! woman can fly an airplane as well as a man!" he said.

"I've flown with few," I said. "There are good women pilots and bad women pilots. Right now the total number is pretty small and any experience you might have had can only be described as anecdotal."

Of course Roy Boy didn't want to hear any of that and I had little choice but to endure his tirade which was, thankfully, short. Roy Boy called our assignment detailers and volunteered for any assignment that got him away from the squadron before "that lady" showed up. Sensing his desperation, they gave him an assignment from the bottom of the stack: a T-37 instructor pilot assignment in the remotest base in Oklahoma. Roy Boy took it.

Roy Boy qualified as a Tweet IP in no time at all, proving he had at least some air sense and potential. His first two student pilots were both women. The story is Roy Boy didn't do so well, didn't get promoted, and left the Air Force well before retirement. In a day when the airlines were hiring anyone with Air Force experience, Roy Boy didn't even apply. I suppose he heard there were women pilots out there.

4

The "we" and not "he" or "she" technique

When I first got to the Boeing 747 (designation: E-4B) it was easy to see that all of the pilots were very good, but one was exceptional, Major Steve Kowalski. The Boeing 747 is exceptionally long and pilots are trained to aim beyond two-bar VASI and for the far set in a three-bar VASI. With no VASI at all, you are aiming 1,500' down the runway instead of the usual 1,000'. You have a lot of airplane behind and below you. And that's what everyone did. Except Steve.

Nobody said anything because Steve was exceptionally good. Sitting in the opposite seat from Steve during landing always made me nervous. But the aft set of wheels always touched down in the first couple of hundred feet of runway. He seemed to know what he was doing. That is, until one day he planted the airplane on the first inch of the overrun at Andrews Air Force Base. The Boeing 747 has a unique footprint. No other airplane has the same 18-wheel signature. It was obvious who was to blame.

The commander didn't blame anyone. At our next pilot's meeting he let US know that WE had a problem. WE had lost sight of the importance of landing on speed, on centerline, in the touchdown zone, following a stable approach. If WE wanted to continue to enjoy a spotless safety record, WE had to do better.

WE all knew who he was talking about.

You may argue that HE also knew who was being talked about and that HE also knew this was nothing more than a charade. But it allowed HIM to save face and play along. HE became our biggest advocate for landing in the touchdown zone.

I would argue that a more direct approach would have had far different results.

5

The "find a new angle" and not "repeat yourself" technique

By the time I became a civilian I had my full of pilots who thought the best way to instruct was to say something and if that didn't work say it again only louder. We are all different and sometimes the correct learning method for one person is wrong for the next. As instructors, it is our job to figure out how to get our points across; it isn't up to the student to read our minds. And that also applies when not in a formal learning environment . . .

The winds were 360 at 10, giving us almost a direct crosswind for our landing on Houston Intercontinental’s Runway 26 Right. It was well within limits for our Challenger 604 landing on a dry runway and would not be a problem.

“Ask for a circle to Runway 15,” Gary said from the left seat. He was the pilot in command and the chief pilot, so he was the boss.

“That will give you a pretty strong tailwind,” I said. “It doesn’t save you that much time, you really ought to stick to this runway.”

“I didn’t ask you, I told you to ask tower for the circle. Don’t you Air Force toads know how to follow orders?”

Gary was retired Army and I was retired Air Force. The biggest thing he flew in the military was a King Air turboprop. The Challenger 604 we were flying was the smallest airplane I had flown in over 20 years. I asked for the circle and we were cleared.

“You’ve got a ten knot, quartering tailwind from the left, Gary.”

“Noted,” he said.

He landed the airplane. As soon as the nose was on the runway, he pushed the yoke full forward and hard right.

“Whoa!” I said as the airplane banked right and the left wheel almost broke ground. I grabbed the yoke and reversed it to full left.

“Get your damned hands off my airplane!” he yelled. I didn’t.

Gary brought the airplane to taxi speed and I relaxed my death grip on the yoke. What followed from him was a non-stop diatribe on the differences between the pilot in command (him) and the second in command (me). Once we were back at the hangar and the passengers were gone, he pointed to his office. I followed him as he continued the monologue to include the differences between the top branch of the U.S. military (the Army) and those of lesser status (the Air Force). A flag from the Military Academy at West Point sat behind his desk, the Army Mule looking me in the eye as he berated me.

I kept my mouth shut through it all and waited for the inevitable, “Well, aren’t you going to say anything?”

“Why did you roll the airplane away from the wind after landing?” I asked. “Every airplane I’ve ever flown has you roll into the wind.”

“You’ve never flown a real airplane like this,” he said. “We require you to ‘dive away’ from the wind when in a tailwind. Ask any civilian pilot and they will tell you that.”

The next day I elected to ask the finest civilian pilot I knew. Kevin flew the Challenger about as well as anyone I knew and also had his own Stearman.

“That’s a taxi technique for tail draggers,” he explained. “You don’t want a tailwind lifting the tail or a wing when you taxi. If you ‘dive away’ from the wind, the elevator points down so the wind goes over it and pushes the tail wheel onto the taxiway. It also moves the upwind aileron down to keep the wind from lifting the wing.”

“Does it always work?” I asked.

“Well the elevator part only works for tail draggers,” he said. “If you were to do that on a tricycle airplane, it could actually lift the nose and cause you to lose nosewheel steering.”

“What about for a tailwind that is less than taxi speed?” I asked.

“What do you mean?” He asked.

“If I have a 10 knot tailwind trying to push the tail down because I ‘dive away’ from it, but let’s say I am taxiing at 20 knots, isn’t there a net 10 knots of wind underneath the elevator? In that case, won’t the ‘dive away’ actually lift the tail?”

Kevin thought silently. He pulled out a Post It note from nearest desk and started to draw. “Yeah,” he said. “I guess it would. I’m going to have to add that to my bag of tricks. Thanks!”

A month later I was in the left seat of our Challenger with Gary in the right. We had to taxi half the length of Runway 15 before takeoff and the winds were from our back-right. I pushed the yoke full forward and hard left with my right hand, keeping my left hand on the nosewheel tiller. It probably looked as awkward as it felt.

“What in the hell are you doing?” Gary asked.

“I’m diving away from the tailwind,” I said.

“It doesn’t matter at this speed,” he said. “You only do that at high speeds.”

“Oh,” I said, feigning ignorance. “Maybe you can help me understand once we level off.”

“I can do that,” he said. “Always happy to teach you Air Force ‘wang nuts’ a thing or two.”

I took off into the wind and pointed us west. Gary was uncharacteristically quiet during the climb but regained his normal personality once we had leveled off.

“So you want to learn when you ‘dive away’ from the wind and when you don’t.”

“I do,” I said.

“Well you just do it when you have a tailwind,” he said.

“When I am doing 100 knots indicated airspeed, do the flight controls know we have a tailwind?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. But he didn’t continue and didn’t want to talk about techniques with me anymore.

The next month the boss was headed for recurrent and I called a friend at the training center for some help. “Have the instructor give him a gusty quartering tailwind for a landing,” I asked. I explained my reasoning and the trap was set. I never got the details about what happened, other than it was “a learning experience.”

A month later one of our pilots almost got a wing tip in a quartering tailwind. What he got was a flap hinge, ground about a half an inch by the runway. He was an excellent pilot with very little experience in aircraft as large as a Challenger. The rest of us pilots only heard bits and pieces of the dressing down the flap hinge pilot got from Gary behind closed doors.

“What in the hell were you doing,” Gary yelled. “You turn the ailerons into the wind to keep the wings level! Every numb nuts knows that!”

There was a muffled response.

“Dive away from the winds!” Gary yelled. “You aren’t flying a damned Citabria! You got to learn to fly jets with the big boys, son!”

Of course it was gratifying to know Gary had learned the error of his ways while trying to instruct me to follow his errors. But I had failed to realize the damage his previous instruction could have already done to my peers. But at least he learned. He was known for his stubbornness, but at least he learned.

6

The "de-escalate" and not "escalate" technique

There are hierarchies of pilots, even in the civilian world. Most of these appear to be arbitrary and, if anything, just in the eye of the beholder. Many corporate pilots seem to think the title "international captain" carries the most weight of all. Among international captains the higher status goes to the one who has been to the most regions of the world. There can be a conflict, however, when a new pilot shows up with a different idea.

Barney had been a corporate pilot most of his professional life and had seen every corner of the world. He thought he knew everything there was to know about international aviation and never passed an opportunity to let every other pilot know his knowledge was superior to theirs. He eventually ended up in charge of a three person flight department where he was in charge of hiring. He had to do a lot of hiring because few pilots would put up with him for more than a year or so.

A month before I showed up Barney hired Thomas, a former airline pilot who had a fair amount of domestic experience but had spend the last two years as a first officer designated to fly as an international relief pilot on the long hauls between California and Hawaii. While Barney considered the SFO to PHNL run hardly international at all, Thomas considered corporate operations to be hardly aviation. As far as Thomas was concerned an airline pilot, especially one who flew for the "main line," was the best kind of pilot there was. We in the corporate world were in a lower class. And that's when I showed up.

"Thomas doesn't know the first thing about crossing the Atlantic," Barney said to me before sending me to Switzerland with Thomas as my SIC. "Keep an eye on him."

Thomas did a competent job on the HF but seemed to be lost with a plotting chart. I didn't say anything, thinking I could demonstrate the proper procedure on our return leg. I verbalized my method for plotting the Equal Time Points and Thomas seemed to pay attention, without openly looking like he was paying attention. When I handed him the complete plotting chart he handed it back, "I know how to do that."

"I was hoping you would check my work," I said. "I would hate to get violated if I made a mistake you would have caught." He took the chart and studied the lines against our master document.

"It's fine," he said.

It seemed Thomas didn't know what he needed to know, but didn't want to ask for instruction or even admit that any instruction was needed. Even when asked questions that would have allowed him to shine, he wasn't interested in any exchange of information. We were flying his old route between San Francisco and Honolulu and I asked for the "main line's" procedure on Pacific he only said, "we had our own charts." When pressed, "it isn't half as complicated as Barney wants you to think it is. He really is a self-important dweeb."

I flew the next trip with Barney and got an earful about how lacking these airline pilots were in international procedure knowledge. "He doesn't know the first thing about ETOPS. And he wonders why I haven't allowed him to upgrade to PIC!" Of course we were not operating under Extended Operations rules so I wasn't sure what Barney's point was. That night, in the hotel, I confirmed my suspicions about ETOPS but Barney dismissed them. "Of course we don't operate under ETOPS, but I was testing Thomas. I doubt he even knows that it stands for 'Extended Twin-engine Operations.'" Of course the "Twin-engine" part of the acronym was dropped years ago. But I didn't correct him.

I spent half my time with Thomas and the other half with Barney. The flights with one were filled with complaints against the other. I didn't understand how Barney saw any advantage to belittling Thomas when it was in his best interest for Thomas to learn. And it was even more mystifying that Thomas was willing to get into this war of wills with his boss. It didn't make any sense.

A year later Barney quit to take a higher paying job with another company. I was promoted to take his place and his only words of advice had to do with keeping an eye on Thomas. On our next trip to Europe, Thomas cursed himself after forgetting a Post Position Plot within our ten minute guideline.

"Nailing the ten minutes isn't a big deal," I said. "We just want to get it around ten minutes. When I am heading east or west I just look for the next two degrees of longitude. That way I only have to interpolate the latitude. Besides, you can use the 'cross points' on the FMS to make it even easier." I reached over to his FMS and set up the post position plot over the next even longitude. "See, it even predicts our latitude when I tell it 28 west. It is more accurate to do it this way."

Thomas tried it my way after the next waypoint and I could detect a self-satisfied smile. "You know if only Barney could have done some actual instruction like that, we would have gotten along a lot better."

"He does tend to make all this a game of one upsmanship," I admitted. "If you take him down a notch or two, he gets better."

"Well he treated you differently than me," he said.

"I noticed that," I said.

So my relationship with Thomas got instantly better. I still talk to Barney now and then; he likes to continue to harp on Thomas' short comings. I wonder if he'll ever let go. Thomas still holds a grudge too. I wonder if either one had just let it go if the whole situation could have been avoided.

References

(Source material)

Air Training Command (ATC) Regulation 51-38, Advanced Flying, Jet, 15 June 1989

Strategic Air Command and the Alert Program: A Brief History, Office of the Historian, Headquarters Strategic Air Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, 1 April 1988