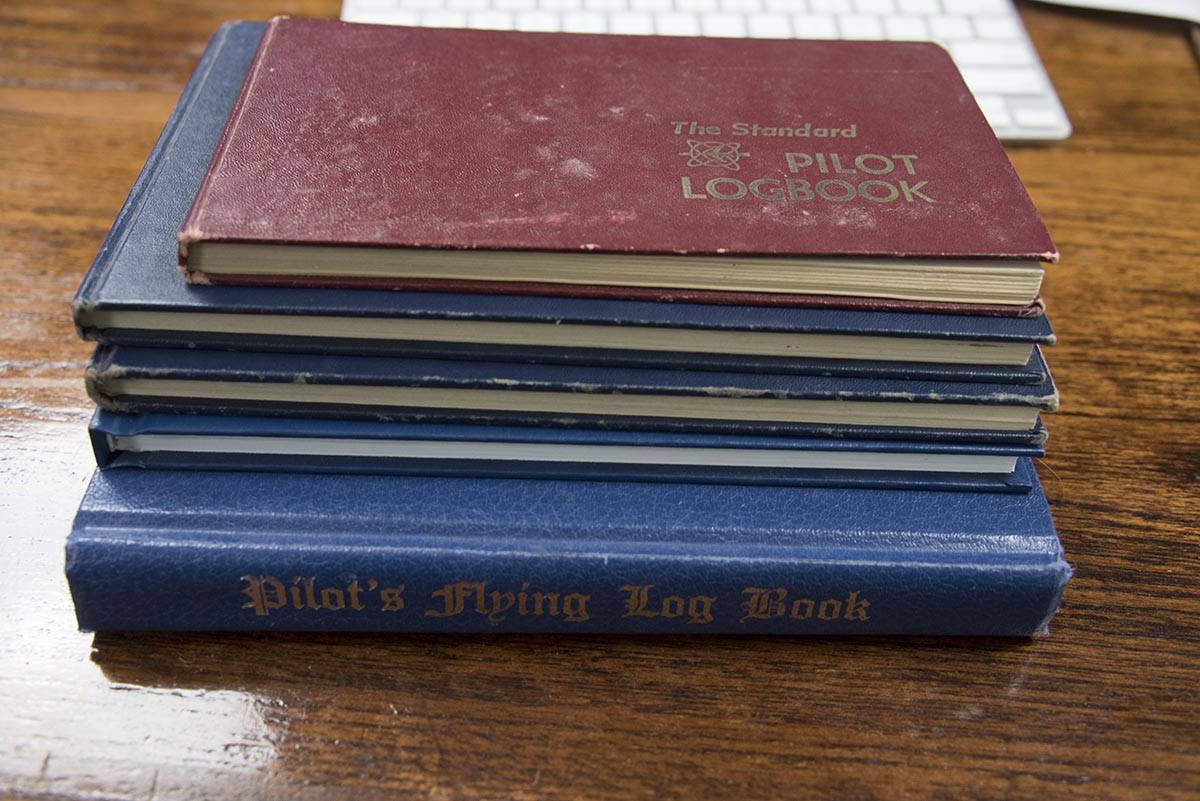

After 43 years of flying I have accumulated about 11,000 hours of total flight time. Compared to my peers who went to the airlines, that isn't much. I feel like much of those 43 years were spent in a battle to remain proficient, even though I was always current. That begs a few questions.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-11-01

First of all, what do the words currency and proficiency mean? In the FAR dealing with certification (14 CFR 61), the FAA really only uses the word proficiency when they mean currency and only uses the word currency when talking about recency of flight experience in one particular helicopter. The dictionary definitions aren't much help. Perhaps we need to define the words in terms of aviation and press on from there . . .

1

Currency and proficiency defined

What the words mean

The dictionary definitions of both words aren't of much use to us. The closest fit of each word:

The dictionary definitions

Currency: the fact or quality of being generally accepted or in use.

Proficiency: A high degree of competence or skill; expertise

Currency: what we aviators mean

When we say "currency" or "recency," we mean compliance with specific minimum stipulated requirements over a preceding period of time. These are usually stipulated by government regulators, but the stipulations can also be made by the companies we work for, our insurance brokers, and other organizations with a stake in the safety of our operations.

Proficiency: what we aviators mean

When we say "proficiency," we mean being able to achieve a desired level of performance because we have performed the actions in question with enough recent practice to reliably perform up to that desired level of performance.

2

Legal requirements

In the United States, most of the legal requirements are given in the Federal Aviation Regulations, more properly called Part 14 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR). U.S. pilots who venture beyond their borders are also constrained by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) where regulations are given in Annexes and Documents.

There is no "one size fits all" list because the more a pilot is authorized to do, the longer the list of regulatory requirements. But in general, the following list should give you an idea of where to look.

Medical certificates

In the U.S., the duration of your medical certificate depends on your age and the type of operation you are flying for. Duration is based on calendar months so that expiration dates fall on the last day of the month. In the ICAO, the duration is based on the license type and expirations fall on the date of the previous exam.

You can find out about U.S. medicals in 14 CFR 61. Specifically, for airline transport pilots look to 14 CFR 61.23. Other pilot types are covered just prior to that section.

You can find out about ICAO medicals in Annex 1, starting at paragraph 1.2.4.

Recency of flight

In general, all pilots will need to be concerned with having recently performed a minimum number of takeoffs and landings within a specified time frame. In the U.S. this will be 3 takeoffs and 3 landings in the previous 90 days to qualify to act as the Pilot in Command (PIC) with passengers on board. If you are instrument rated, you will also have instrument-related requirements. All of this is covered in 14 CFR 61.57.

If you fly internationally, you will need to be concerned with the rules in ICAO Document 6, which comes in three volumes. Volume I concerns commercial operators. Volume II concerns General Aviation. Volume III concerns helicopter operators. The general aviation requirements are in ICAO Doc 6, Vol II, section 3.9.4.

There will be requirements in other countries that may affect you and you will need to research the Aeronautical Information Publication for each country.

Can both pilots log the same approach or holding pattern?

I would say the answer is no, with one exception. The exception is that a CFII (certified flight instructor, instrument) may log approaches a student flies when those approaches are conducted in actual instrument flight conditions. And this would also permit that instructor who is performing as an authorized instructor to "...log instrument time when conducting instrument flight instruction in actual instrument flight conditions" and this would count for instrument currency requirements under § 61.57 (c)." (See FAA Legal Interpretation, Ronald B. Levy, 2008)

Further in the 2008 Levy interpretation, the FAA Chief Counsel states: "The regulations expressly permit an authorized instructor conducting instrument instruction in actual instrument flight conditions to log instrument flight time (61.51 (g)(2)). The only remaining issue is whether, even if properly logged, the approaches are considered to have been "performed" by the instructor within the meaning of section 61.57 (c)(1). The FAA views the instructor's oversight responsibility when instructing in actual instrument flight conditions to meet the obligation of 61.57 (c)(1) to have performed the approaches."

No such provision in the regulations permits an SIC, in an aircraft certificated for more than one crew member, to log those same "tasks and iterations" for "the purposes of maintaining instrument currency."

On the contrary, the regulations state with regards to logging instrument time: "A person may log instrument time only for that flight time when the person operates the aircraft solely by reference to instruments under actual or simulated instrument flight conditions." § 61.51 (g)(1) and with regards to instrument experience: "Within the 6 calendar months preceding the month of the flight, that person performed and logged at least the following tasks and iterations..." § 61.57 (c)(1)

I would highly doubt the FAA would consider an SIC monitoring (and without the responsibility and oversight of instructing) an instrument approach flown by the PIC, who is operating the aircraft solely by reference to instruments under actual or simulated instrument flight conditions to have "performed" the approach (or holding pattern) within the meaning of section § 61.57 (c)(1).

(g) Logging instrument time.

(1) A person may log instrument time only for that flight time when the person operates the aircraft solely by reference to instruments under actual or simulated instrument flight conditions.

Source: 14 CFR 61, §61.51 Pilot logbooks

(c) Instrument experience. Except as provided in paragraph (e) of this section, a person may act as pilot in command under IFR or weather conditions less than the minimums prescribed for VFR only if:

(1) Use of an airplane, powered-lift, helicopter, or airship for maintaining instrument experience. Within the 6 calendar months preceding the month of the flight, that person performed and logged at least the following tasks and iterations in an airplane, powered-lift, helicopter, or airship, as appropriate, for the instrument rating privileges to be maintained in actual weather conditions, or under simulated conditions using a view-limiting device that involves having performed the following -

(i) Six instrument approaches.

(ii) Holding procedures and tasks.

(iii) Intercepting and tracking courses through the use of navigational electronic systems.

(2) Use of a full flight simulator, flight training device, or aviation training device for maintaining instrument experience. A pilot may accomplish the requirements in paragraph (c)(1) of this section in a full flight simulator, flight training device, or aviation training device provided the device represents the category of aircraft for the instrument rating privileges to be maintained and the pilot performs the tasks and iterations in simulated instrument conditions. A person may complete the instrument experience in any combination of an aircraft, full flight simulator, flight training device, or aviation training device.

Source: 14 CFR 61, §61.57 - Recent flight experience: Pilot in command.

3

Additional requirements

Authorizations

You might have training and recency of experience requirements stipulated by Letters of Authorization (LOAs), Operations Specifications (OpSpecs), or Management Specifications(MSpecs). These are covered by FAA Order 8900.1, Volume 3. They should also be mentioned in any applicable LOAs, OpSpecs, or MSpecs.

My operation, for example, requires:

- Regular training in data link operations, required by our LOA A056.

- Training in oceanic and remote continental navigation using long-range navigation systems, required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA B036.

- Training in North Atlantic (NAT) High Level Airspace (HLA), required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA B039.

- Training in Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM) Airspace, required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA B046.

- Training in Enhanced Flight Vision System (EFVS) operations, required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA C048.

- Training in Area Navigation (RNAV) and Required Navigation Performance (RNP) terminal operations, required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA C063.

- Training in the use of Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs), required by company provisions used for approval of our LOA D195.

Insurance

Your insurance company may require initial and regular training in a variety of subjects. Our insurance, for example, gives us reduced rates provided all pilots, technicians, and line service personnel have the following training:

- Fatigue risk management

- Safety Management System

Additionally, pilots should have:

- Upset prevention and recovery

- Aircraft simulator recurrent

- International operations

Local Regulatory

Our state and our airport each have regular training and certification rules that require pilots to keep up-to-date. At Hanscom Field (KBED), Massachusetts, for example, badging requirements are more strict on local pilots than they are for visiting aircrew. Badges must be renewed every two years and if expired, the pilot may not be escorted onto the ramp.

Company

Our company also requires regular training in several areas not specified elsewhere or with greater frequency. Recurrent simulator training, for example, is required once every 6 months and type-specific training is required once every 12 months. Training that is recognized industry wide as a "good idea," is mandated and often with specific time periods. Cold weather operations, for example, is required annually.

4

Proficiency requirements

I think of currency as what is needed to satisfy "them," the regulators, insurance brokers, and our company. I think of proficiency as what is needed to satisfy me, my need to be good at what I am doing if charged with doing that on behalf of my crew, passengers, and the company.

The simplest way I know of making the "Am I proficient?" determination is to ask myself another question: Would I pass a type rating checkride? If the answer is no, I believe I am not proficient. This may seem to be an unreasonably high standard to some. But remember you are being paid to not only fly the airplane on a bog standard day, but to be able to safely handle whatever comes your way. Specifically:

- Can I recite all required memory items without hesitation?

- Do I have all applicable limitations committed to memory?

- Am I comfortable with all normal procedures from the start of flight planning through the completion of the flight?

- Can I quickly reference and use all available cockpit materials to handle all abnormal and emergency procedures?

If the answer to any of those is no, I have work to do. More about that next . . .

5

Strategies

An individual

When I find myself failing the Am I proficient? question, I find it helpful to read my notes from my last initial or recurrent training to judge just how unproficient I am. Then, depending on the severity of my shortcomings, I'll mimic what I do to prepare for recurrent:

- Review memory items and aircraft limitations

- Review aircraft systems

- Electrical system

- Fuel system

- Hydraulic system

- Flight control system

- Fire protection system

- Powerplant system

- APU system

- Landing gear and brakes system

- Pneumatic system

- Air conditioning system

- Pressurization system

- Ice and rain protection system

- Oxygen system

- Water and waste system

- Review procedures

I keep a set of flash cards on my phone so I can always review aircraft memory items and limitation when I have a spare moment. There are a lot of applications out there. I use Quizlet. The Quizlet flashcards I wrote for GVII limitations are available here: G500 Limitations. You can navigate from there to the decks on various GVII systems. I find these especially useful when I am in a waiting line someplace or dining in a restaurant alone.

I'll pick a different system to review each day, limiting my study to one hour. This keeps this task from becoming a burden. If I know it is just an hour, I am more apt to do it.

I also have Quizlet decks devoted to each system.

Following my one hour systems study, I'll pick a different normal and abnormal procedure to review.

During this preparation, I'll look for opportunities to sit in the aircraft and review checklist procedures. I'll ask our mechanic for time to watch maintenance procedures and other opportunities to be hands on with the aircraft.

The whole flight department

What if the need to monitor currency and proficiency is impacting the entire flight department? During the 2020-2022 pandemic, here is what my flight department instituted:

- We encouraged everyone to follow the regimen given earlier for an individual.

- We conducted a weekly local out and back training flight with specific instructions to go out and do a full shutdown, get some lunch, and then return. This simulates an out and back trip and gives two pilots a takeoff and and instrument approach and landing.

- We conducted a monthly local overnight training flight, to ensure crews remain proficient with the normal "put the aircraft to bed" and "bring the aircraft back to life" routines without home base support.

- We conducted monthly training sessions, requiring a different pilot each month to prepare and present on a topic of the group's choosing.

6

Additional strategies

The strategies given in the previous section are my own. I've heard from others who have other great ideas.

Chair fly trips

You might consider going through all the motions required to fly a basic trip, short of actually flying the trip. Do all the airport research, weather checks, and gather all the required information. Then sit down with your checklists and mentally practice everything you would do on a live trip.

Additional simulator trips

During the height of the 2020 pandemic, some simulator vendors offered their clients discounted simulator sessions. Full service clients at one vendor got a limited number of free hour-long sessions even without the discounts, it might be money well spent to arrange a crew simulator.

References

(Source material)

14 CFR 61, Title 14: Aeronautics and Space, Certification: Pilots, Flight Instructors, and Ground Instructors, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation