The first part of this book takes place in Hawaii, where Eddie completes the journey from copilot to the left seat, then to instructor, and then to flight examiner. There is a lot of learning going on. Eddie goes from a wet behind the ears first lieutenant copilot, to what he thought was a well seasoned flight examiner captain.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-01-01

He learned a lot, but he wasn't sure how all that happened. The second part of this book takes place in Omaha, where Eddie thinks he is about the undergo the same song, second verse. But he ends up learning how to learn. (And that was the best lesson of all.)

Our story begins . . .

The secrets began on day one

1982

The secrets began on day one. “It is the tan building behind the airplanes,” he said on the phone. “Park in the lot just mauka, come to the gate and ask for me. There are no signs.”

“Okay,” I said, “see you.” He assumed I knew mauka meant toward the mountains.

I knew my sponsor was Hawaiian from his name, Captain K. Walter Kekumano. That’s about all I knew. Since the 9th Airborne Command Control Squadron had a secret mission, few on base knew it even existed. The four Boeing 707s, designated EC-135Js, were pretty silver and white birds with nothing to give away their mission except the words “United States Air Force” along the length of the fuselage. From the unmarked parking lot I could see the four tails towering over the bunker that I assumed would be my home for the next several years. The building was surrounded by barbed wire and the solitary front gate was guarded by a sentry with a rifle. In the periphery I saw two more guards in standard issue blue trucks.

As I approached the gate, I noticed a single sign notifying me that the use of deadly force was authorized. As the guard studied my orders and picked up a phone, I looked beyond the fence to the building. Two dark brown doors, one of which had the familiar 9ACCS squadron patch, set off the light brown exterior. The nearest door suddenly opened and a tall, dark haired captain strolled out, smiling. He waved at me and shot the guard a thumbs up. The gate opened and I entered, saluting the captain. “Good morning, sir.”

“Call me Walt,” he said, returning my salute. “It will be nice to have another local pilot here,” he said.

“How many we got?” I asked.

“Including you and me?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Two,” he said. “And don’t call me sir. You can call the majors and lieutenant colonels sir, but you and me are the same. We copilots got to stick together.”

We entered the squadron just as two majors were leaving. The shorter major looked me in the eye briefly and then back to the other major. “Christ,” I heard him say, “a damned lieutenant.”

“Don’t let him bother you,” Walt said. “That’s Greco. He hates everyone.” I got the nickel tour as we gathered all my in-processing paperwork, my new flight manuals and flying regulations, and a new set of flight suit patches. The scheduling office had the standard grease pencil board probably found in every Air Force squadron, this one with five crews on top and unassigned extras on the bottom. That’s exactly where my name was. I had a flight scheduled in a week.

“You get as many rides as you need,” the scheduler said. “Then you get a check ride. But don’t take too many. The more rides you take, the meaner Greco gets.”

“Ten rides is the record,” Walt said. “Most guys get good enough to hang on to the tanker by five or six. Don’t worry about Greco. He has a rough exterior but he hardly ever busts anybody.” I scanned the board and noticed three empty slots for copilots. I knew from experience that when a squadron is short copilots, training gets rushed and check rides get easier.

A week later I was approaching the new airplane for the first time with my instructor pilot, Major Bobby Duff. He wore senior pilot wings and wanted to talk about sports, politics, or anything other than the EC-135J. “It is just another airplane, Eddie. Don’t worry about it.”

After two years of flying a gray tanker with tiny little engines and an empty cargo bay, the new bird was like eye candy for a pilot. The EC is white and silver, has massive engines, and is covered from nose to tail with strange and wonderful antennas. The interior is filled with communications equipment, passenger seating, and two things I had never had before on an airplane: a flush toilet and a galley. It was all a treat, but nothing caught my eyes more than the engines.

“Are they reliable?” I asked Major Duff as we approached.

“Haven’t lost one yet,” he said. “Lots of thrust at your command at a moment’s notice.”

I lowered myself into the right seat, opened the checklist, and started flipping switches. Once or twice I came upon something I’d never heard of before and Major Duff would point to the new gizmo and I would move on. Duff spent most of his time chatting with the navigator or giving an endless editorial about the state of the Air Force promotion system. His monologue continued into the flight.

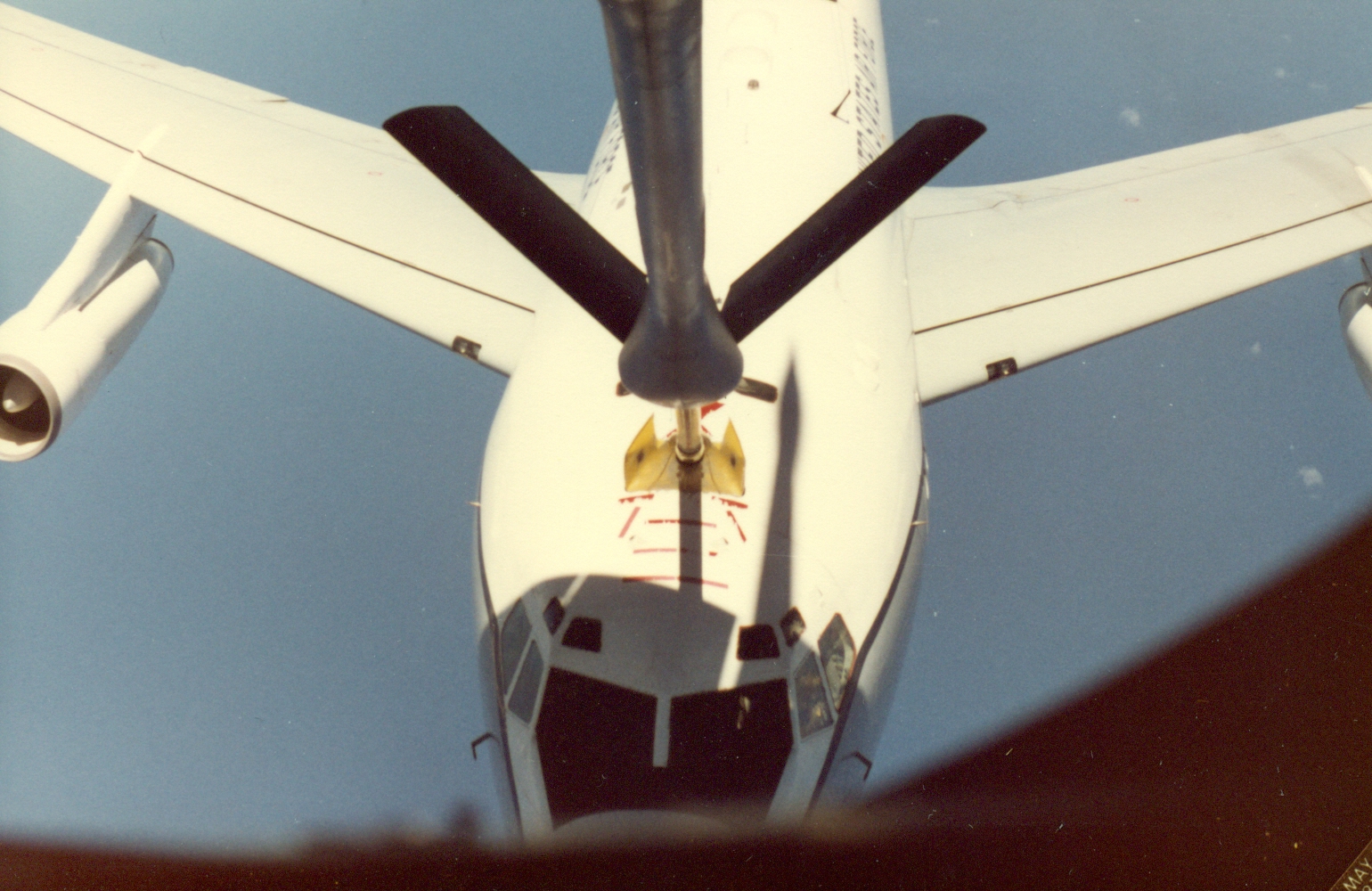

He flew the airplane almost as an afterthought. He manipulated the controls and glanced outside now and then, but he spent most of his time with a running commentary about what our navigator was doing during the rendezvous with the tanker. Once he spotted the tanker, he moved on to a play-by-play of the tanker’s maneuver. Our airplane was flying a very smooth line from a mile back and a thousand feet below, around 310 knots. In a few minutes we were fifty feet behind the tanker and at 275 knots. My only duties were to open the fuel receptacle doors and the three or four valves needed to escort the fuel from the tanker to our wing tanks. I stole a few glances of the throttles and Major Duff’s hands to decode the secret of getting an airplane flying at over 400 knots true airspeed to within 50 feet of another airplane safely. It remained an act of magic.

“Stabilized, pre-contact, ready,” Major Duff said on frequency. The boom operator acknowledged and we slowly advanced toward the tanker. As the boom traced a line over our heads, I could hear a whoosh until the clunk of metal-to-metal contact.

“Pumping gas,” the boom operator said. I looked down to see our fuel panel lights acknowledge the fact.

“See how easy this is, Eddie?” Major Duff pointed to a UHF antenna on the bottom of the tanker with a white line painted just forward. “Just make the antenna and the line an upside-down T and you can’t go wrong.”

But how do I do that? The tanker would attempt to fly straight and level and provide a stable platform. But flying our 300,000 lb. airplane precisely behind and below at 25,000 feet was hardly child’s play. Ailerons, rudders, and elevators have less air to bite in the thin air and I could feel the airplane wander in each axis. I could see more than a few ways to go wrong; it was as if he told me the perfect golf shot was hitting the ball 300 yards off a tee into a small cup in the ground. Easy. And I had a check ride to face.

He explained that all a copilot had to be able to do was take control of the aircraft in case the pilot was incapacitated and move the airplane aft in a controlled manner. “So I’m going to give you the airplane and we’ll see how long you can hang on. Ready? You got the airplane.”

I tried to keep my control inputs as small as possible, but in just a few seconds we were moving right. “Left ten,” the boom operator commanded. I dipped the left aileron just a little and soon I heard, “right ten.” There seemed to be a time delay built into each control surface, with the magnitude and duration of the delay determined by a Las Vegas bookie. I was unable to predict the outcome of each input. The oscillations only got worse and before we knew it I heard the boomer announce, “disconnect.” I was startled by the boom flying over our heads and jerked the throttles back. In just a second we were a half-mile in trail. I added an inch of throttle and felt the nose of the airplane jerk up. “Geez!” I heard from the navigator.

“These engines are very responsive,” I said. I started to formulate another wry comment to explain my inept performance, but was interrupted by the unmistakable sound of the navigator losing his lunch.

Major Duff laughed. “Believe it or not,” he said, “this isn’t awful for your first try.”

“Speak for yourself,” the navigator said.

“Maybe if you add a little rudder things will smooth out for you,” Duff said. I did that but things just got worse. Once we ran out of tanker time we headed for Kona Airport, on the Big Island of Hawaii. I was prepared for the airplane to have even more Dutch roll than the tanker and was not disappointed. The EC-135J has bigger engines, slightly larger wings, and essentially the same flight controls. Both aircraft were designed before aeronautical engineers really understood Dutch roll on a swept wing jet and the Air Force never bothered installing electronic fixes. Both aircraft required active pilot inputs to stay right side up. But I was a pro with Dutch roll.

“Very nice,” Duff said as I lined up on the 6,000-foot runway jutting out from an ancient lava flow. At 50 feet I brought the throttles to idle and felt the aircraft sink. “I got it,” Duff said. He shoved the throttles forward and we climbed back to pattern altitude. “Let me show you one.” As he brought the airplane back around, I tried to analyze what had happened. When I brought the throttles back, the lift disappeared. It didn’t make sense.

“We are almost 50,000 pounds heavier than that tanker you used to fly,” he said. “You can’t chop the power. As we descended through 50 feet, he pointed to the throttles. “Watch this.” He pulled them very slowly and they never really got to idle until the wheels touched. “See? See? You try it.”

That worked for some reason I didn’t understand; every approach and landing after that was just fine. My training record was 90 percent praise for instrument approaches and landings, but under the column for receiver air-refueling he entered only two words: “needs work.”

I rushed home to my engineering texts and aircraft manuals in search of an answer to the mysterious new engines. I had never worked a day in my life as an engineer, but an engineering degree left me thinking of myself as an engineer first, pilot second. I understood why the airplane pitched up with added power behind the tanker almost as soon as it happened. The engines are below the wings and adding thrust to all four would pitch the nose up. But I hardly added more than an inch of throttle. That kind of power change wasn’t unusual in the traffic pattern and the nose never popped up on me then.

The EC-135J’s engines produced 16,050 pounds of thrust of which about half, just looking at the diagrams, appeared to come from the fan of the engine that completely bypassed the core of the engine. The KC-135A’s engine produced just over 9,000 pounds of thrust, all of which came from the engine’s core. None of that engine’s air was bypassed.

Two of my textbooks verified what I had learned that day: higher thrust engines with larger bypass ratios carry more of their power at the top end of throttle travel. Closer to idle the engines put out much less as a proportion of their maximum values. While the EC-135J had more thrust, it was also heavier and the ratio of thrust to weight decreased at lower throttle lever angles. An inch of throttle at low power settings changed thrust by a little. An inch at higher power settings, at 25,000 feet behind a tanker for example, changed thrust a lot.

I looked at my notes with a satisfaction only an engineer could appreciate, knowing I had solved my throttle and pitch issues. But that smugness came to an end when I realized I still didn’t have an answer to my air refueling mystery: how do you keep the airplane centered behind the tanker plus or minus 8 degrees?

The next day I was introduced to the rest of the copilot force, including a name from my past, Kevin Davies. We shared instructors during pilot training as second lieutenants. As an Air Force academy graduate, he had almost a year of seniority on me. “Captain?” I asked.

“Pinned on last week,” he explained. “Just a copilot, just like you.”

“So what’s the key to air-refueling?” I asked.

“It is a secret,” he said. “If I told you I would have to kill you.”

“It seems that way,” I said. “Any time I asked Major Duff a question his answer was always ‘you’ll get it, Eddie.’ I’m not sure I’m getting anything.”

“The thing about being in a small squadron like this,” Kevin said, “one with a one-of-a-kind airplane, is that nobody really instructs. The old heads know what they’re doing and can’t be bothered to teach. You just have to watch and learn.”

“What’s the deal with Major Greco?” I asked.

“Greco sucks,” he said. “He got me on my first check. I busted the oral.”

“Oral?” I asked.

“He picks a topic you are guaranteed to know nothing about,” Kevin said. “He just wants to hear you say something wrong so he can prove he’s smarter than you.”

“I’ve never been offered a practice oral,” I said. “I wonder if I can get an instructor to do that for me.”

“Don’t bother,” Kevin said. “You only get an oral on your initial check and nobody but you cares.”

Training sortie two was with instructor pilot Major Don Wortham. “Keep your feet off the rudders,” he said as I corrected from five degrees left of the tanker. “Those things can kill you at this altitude.” Like Major Duff, Wortham flew with a nonchalance that disguised any real effort, never deviating from the center of the air-refueling envelope. He let me fly it even when the boom operator’s voice raised an octave or two. I managed to hang on to the boom for a good sixty seconds before falling off.

“That’s going to do fine,” Major Wortham said. “You are ready for a check.”

“What?” For the first time since pilot training, I felt completely unprepared for an assigned task. With three years as an Air Force pilot I had become accustomed to grasping concepts sooner rather than later and eventually flying every maneuver just as the textbook demanded. But there was no receiver air-refueling textbook and measuring my abilities against the pilots I had flown with only pointed to my shortcomings. Now I was up against a major that hates lieutenants and has his own standards. My official pilot record book included fifteen check rides, all of them either “Exceptional” or simply “Qualified.” But none of them were failures. Yet.