Transforming your craft from an oceanic vessel back to domestic operations is just a matter of making the right contacts, finishing some paperwork, removing SLOP (if any), and getting the cockpit ready for airways, radar contact, and full time air traffic control.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-12-25

This section continues an example G450 trip from Bedford, Massachusetts (KBED) to Geneva, Switzerland (LSGG), to Tokyo, Japan (RJAA), back to Bedford. For the purpose of covering an oceanic departure, this section will focus on the KBED to LSGG leg. To view the steps required prior to oceanic airspace entry, see: Oceanic Departure. For the en route portion, see: Oceanic En Route.

1

Coast-in navigation accuracy check

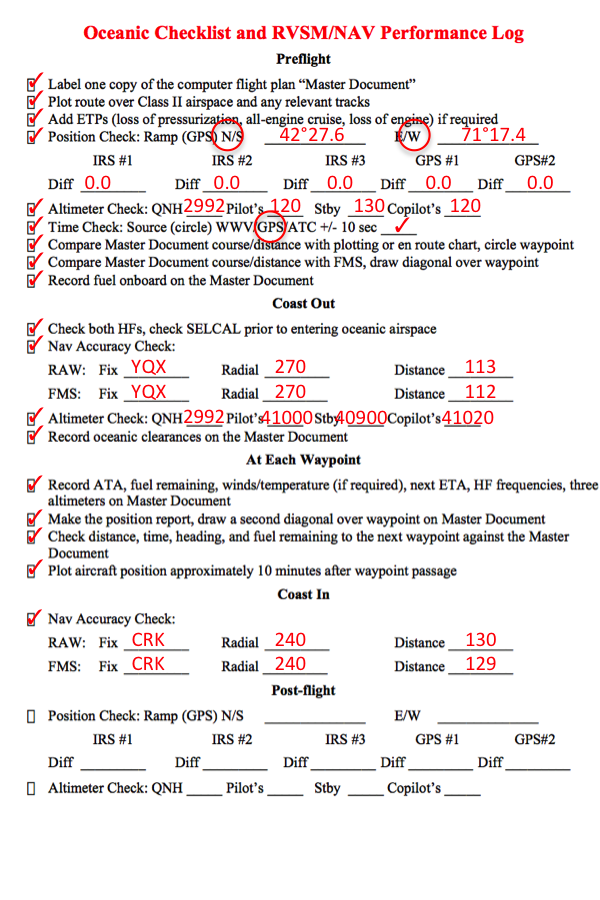

Compare LRNS to ground-based NAVAID (as applicable depending on your equipage). 1. When departing oceanic airspace and acquiring ground-based NAVAIDs, you should note the accuracy of your LRNS compared to the position information provided by those NAVAIDs. 2. You should note discrepancies in your maintenance log.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.11.3

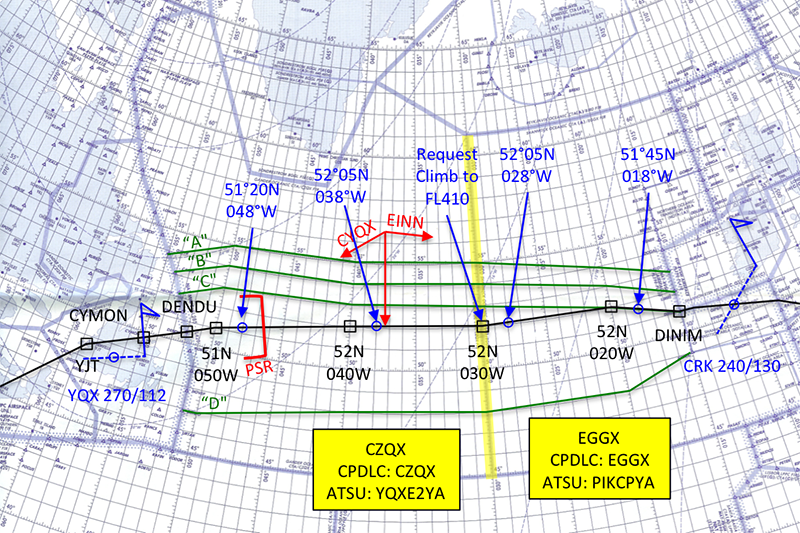

The coast-in navigation accuracy check is conducted in the same manner as for coast-out, except that the earliest possible navigation aid is sought for the first opportunity to check navigation performance, keeping in mind the service volume of the navaid is limited.

More about this: Navigation Accuracy Check.

2

Coast-in

Strategic Lateral Offset

Remove strategic lateral offset. You must remove the strategic lateral offset prior to exiting oceanic airspace at coast-in. We recommend you include this as a checklist item.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.11.1

Domestic Routing

Confirm routing beyond oceanic airspace. Before entering the domestic route structure, you must confirm your routing and speed assignment.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.11.2

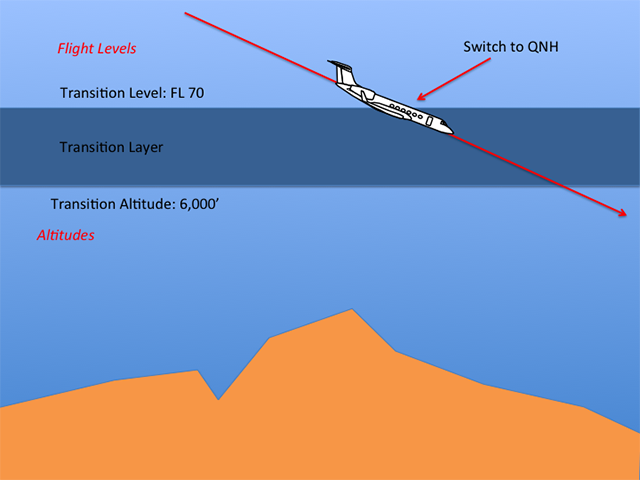

Transition Level.

Transition Level. During the approach briefing, you should note the transition level on the approach plate or verify with ATC. You must reset your altimeters to QNH when descending through the transition level. You should confirm whether the altimeter setting is based on inches of mercury or hectopascals.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.12.1

- Transition altitude: The altitude at or below which the vertical position of an aircraft is controlled by reference to altitudes.

- Transition Layer: The airspace between the transition altitude and the transition level.

- Transition Level: The lowest flight level available for use above the transition altitude.

Source: ICAO Document 4444, Ch 1

More about this: Transition Altitude/Layer/Level.

Other Coast-in Notes

- Position Reporting will be continued until Air Traffic Control instructs "discontinue position reports," or that "radar contact" is regained.

- Mach Number Technique will be continued until returning to domestic airspace or Air Traffic Control approves a change of speed.

- Plotting can be discontinued once the aircraft has returned to Class I airspace.

- Much of your paperwork will need to retained.

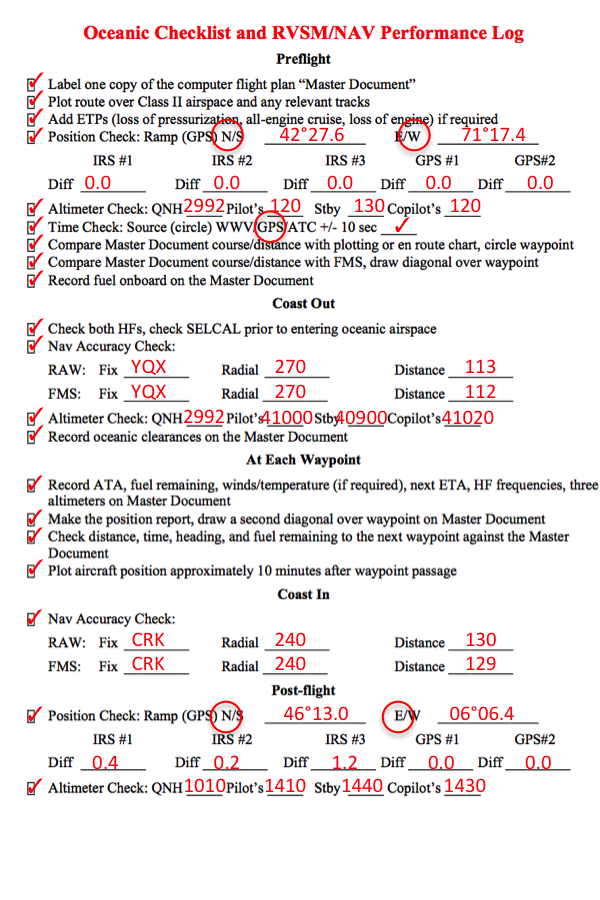

- At the very least you will need to record altimeter readings after landing and if you do not have a hybrid IRU that records inertial performance, you should record those as well. Note: the G450 Hybrid IRU records performance and updates itself after 5 to 15 seconds, [G450 MM §34-42-20, p. 7], so if you want to record it, you need to do so with that time span after landing. It would be a good idea to put your RVSM/Nav Performance log near the top of your paperwork so you don't forget it.

See: Record Keeping, below.

3

Post-flight

When arriving at your destination gate, you should note any drift or circular error in your LRNS. 1. A GPS primary means system normally should not exceed 0.27 NM for the flight. 2. Some inertial systems may drift as much as 2 NM per hour.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.13.1

You must note problems in the altimetry system, altitude alert, or altitude hold in the maintenance log.

Source: AC 91-70B, ¶D.2.14

4

Record Keeping

There doesn't appear to be any written guidance on keeping records of your oceanic flights any more, now that AC 91-70A has been replaced and the newer AC 91-70B doesn't mention record keeping at all. Here is the old guidance:

At the end of each flight, determine the accuracy of the navigational system to facilitate correction of performance. You may perform a check to determine the radial error at the ramp position as soon as the aircraft parks. Radial errors for INSs in excess of 2 NM per hour are generally considered excessive (part 121, appendix G). Keep records on each individual navigation system performance.

Source: AC 91-70A, ¶3-6.t.

- Record Documentation. Decisions regarding monitoring of an aircraft's navigation performance are largely the prerogative of individual operators. In deciding what records to keep, airlines should consider the stringent requirements associated with special use airspaces such as MNPS. Investigating all errors of 20 NM or greater in MNPS airspace is a requirement for airlines. Whether radar or the flight crew observes these deviations, it is imperative to determine and eliminate the cause of the deviation. Therefore, operators should keep complete flight records so that they can make an analysis. The retention of these documents must include the original and any amended clearances.

- Documentation Requirements. Operators should review their documentation to ensure that it provides all the information required to reconstruct the flight. These records also satisfy the ICAO standard of keeping a journal. Specific requirements could include, but do not only apply to, the following:

- Record of the initial ramp position (latitude/longitude) in the LRNS, original planned flight track, and levels.

- Record of the LRNS gross error check, RVSM altimeter comparisons, and heading reference cross-checks before entering oceanic airspace.

- Plotting charts to include post waypoint 10-minute plots.

- All ATC clearances and revisions.

- All position reports made to ATC (e.g., voice, data link).

- The master document used in the actual navigation of the flight, including a record of waypoint sequencing allocated to specific points, ETA, and actual times of arrival (ATA).

- Comments on any navigation problems relating to the flight, including any discrepancies relating to ATC clearances or information passed to the aircraft following ground radar observations, including weather deviations or wake turbulence areas.

Source: AC 91-70A, ¶3-12.c.

There is some guidance in ICAO NAT Doc 007:

Decisions regarding the monitoring of aircraft navigation performance are largely the prerogative of individual operators. In deciding what records should be kept, operators should take into account the stringent requirements associated with the NAT HLA. Operators are required to investigate all lateral deviations of 10 NM or greater, and it is imperative, whether these are observed on ground radar, via ADS reports or by the flight crew, that the cause(s) of track deviations be established and eliminated. Therefore, it will be necessary to keep complete in-flight records so that an analysis can be carried-out.

Source: ICAO NAT Doc 007, ¶11.2.1

Techniques: Paper Records

It may be useful to carry an envelope for each planned oceanic leg, labeled with the following information:

- Date

- Aircraft Registration Number

- Departure/destination

- PIC/SIC/Relief Pilot

The following items, as applicable, should be retained at the aircraft base:

- Master Document

- RVSM/Nav Performance Log

- Navigation Worksheet

- Plotting chart

- Weather reports

- Track Messages

- Over-flight/landing permits

- INOTAMs/NOTAMs

- Post-Flight report form

There is no regulatory guidance on how long these records should be retained. We use six months.

Techniques: Electronic Records

Some online flight planning software provide nearly automatic methods of record keeping. ARINCDirect in combination with their Flight Operations Software (FOS) applications, for example, will archive just about everything done while oceanic. Job Done. But what if your software doesn't offer this capability?

You can take photos — called "screen grabs" — of everything you do on an iPad that is pertinent by pressing the "Home" and "Power" buttons simultaneously. Everything will be saved as a photo to your Photos application. From there it is a matter of sending those photos via an email or text message to whomever does your record keeping.

References

(Source material)

*Advisory Circular 91-70A, Oceanic and International Operations, 8/12/10, U.S. Department of Transportation

* This version of AC 91-70 has been superseded but it retained because it contains older guidance that helps place current guidance into perspective.

Advisory Circular 91-70B, Oceanic and International Operations, 10/4/16, U.S. Department of Transportation

ICAO Doc 4444 - Air Traffic Management, 16th Edition, Procedures for Air Navigation Services, International Civil Aviation Organization, October 2016

ICAO Nat Doc 007, North Atlantic Operations and Airspace Manual, v. 2021-1, applicable from February 2021