I don't post anything on YouTube but I do have a fair amount of video content on the Internet. I do worry about presenting something or saying anything that will get others into trouble.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-03-12

Likewise I tell my kids to be careful about what they post on social media. I know we pilots come from diverse backgrounds and it is hardly a surprise that some pilot YouTube videos are in the careless or reckless category. But when something comes from a major aircraft manufacturer that isn't 100% right, then I really have to wonder.

So that's what happened here. Dassault is obviously very proud of the Falcon 8X and for good reason. But they sent the wrong message with this attempt to set a city pair record. I'll expand on that with two incidents from airshows that will dovetail with the first example. I think there are lessons here.

1 — A manufacturer's bad example

1

A manufacturer's bad example

There is nothing wrong with having bragging rights about an airplane's capabilities, such as the quickest time for a city pair or the ability to land or takeoff on a short runway. But if you are going to do that, it is important to remember the example you are setting for others. Cutting corners, ignoring rules and regulations, or simply bypassing what you consider to be best practices is hardly the way to set records. I am sure it happens all the time, but every now and then a manufacturer goes out of their way to advertise their intentional noncompliance.

Dassault Falcon invited a writer from the magazine Business Jet Traveler to witness a record setting attempt for the time between Santa Monica Airport (KSMO), California and Teterboro Airport (KTEB), New Jersey. They made the attempt even more remarkable by making the attempt after the runway had been shortened from 5,500 to 3,500 feet.

Spoiler alert, they beat the previous record of 4 hours 30 minutes by four minutes and then posted this on YouTube: https://youtu.be/yZI1GqoVB4w.

Watching the video, I was troubled by a few things:

- They crossed the threshold at KSMO at about 10 feet: video.

- They planned their takeoff with only 300 feet to spare (A 3,200' balanced field length for a 3,500' runway).

- They flew above FL 410 without either pilot using oxygen.

- They flew a descent into turbulence that resulted in "definite zero G moments."

- They appeared to cross the threshold at KTEB below 10 feet: video.

I imagine the pilots will tell you they are highly experienced, they planned everything in great detail, and they trained to do this. To that I would like to suggest that there are thousands of accident reports out there recording the deeds of many highly experienced pilots who were let down by their planning and training. But there are a few things else that they and Dassault should consider.

- They have now demonstrated that operations out of a 3,500 foot runway with obstacle and noise challenges are okay with the Falcon 8X.

- They are in effect condoning: crossing the threshold by just a few feet, ignoring oxygen rules, and flying a rushed descent for the sake of saving four minutes.

- They have demonstrated for the world that safety isn't their first concern when it comes to promoting the aircraft's capabilities.

- They are inviting all other Falcon 8X pilots to do the same.

If you are still thinking, "I would have done it and bragged about it!" Here are some more things to ponder: Careless or Reckless Operation.

2

Airshow

I was an "airshow pilot" for a few years and that is a story in and of itself, but more on that later. The first airshow I flew was as a copilot in our Air Force Boeing 747 (E-4B) in 1986. The next year the Strategic Air Command started an airshow team with the less than impressive name, "Thunderhawks." I saw them perform a month before they crashed. There was an obvious lesson, but sometimes it takes first hand tomfoolery for a lesson to take hold.

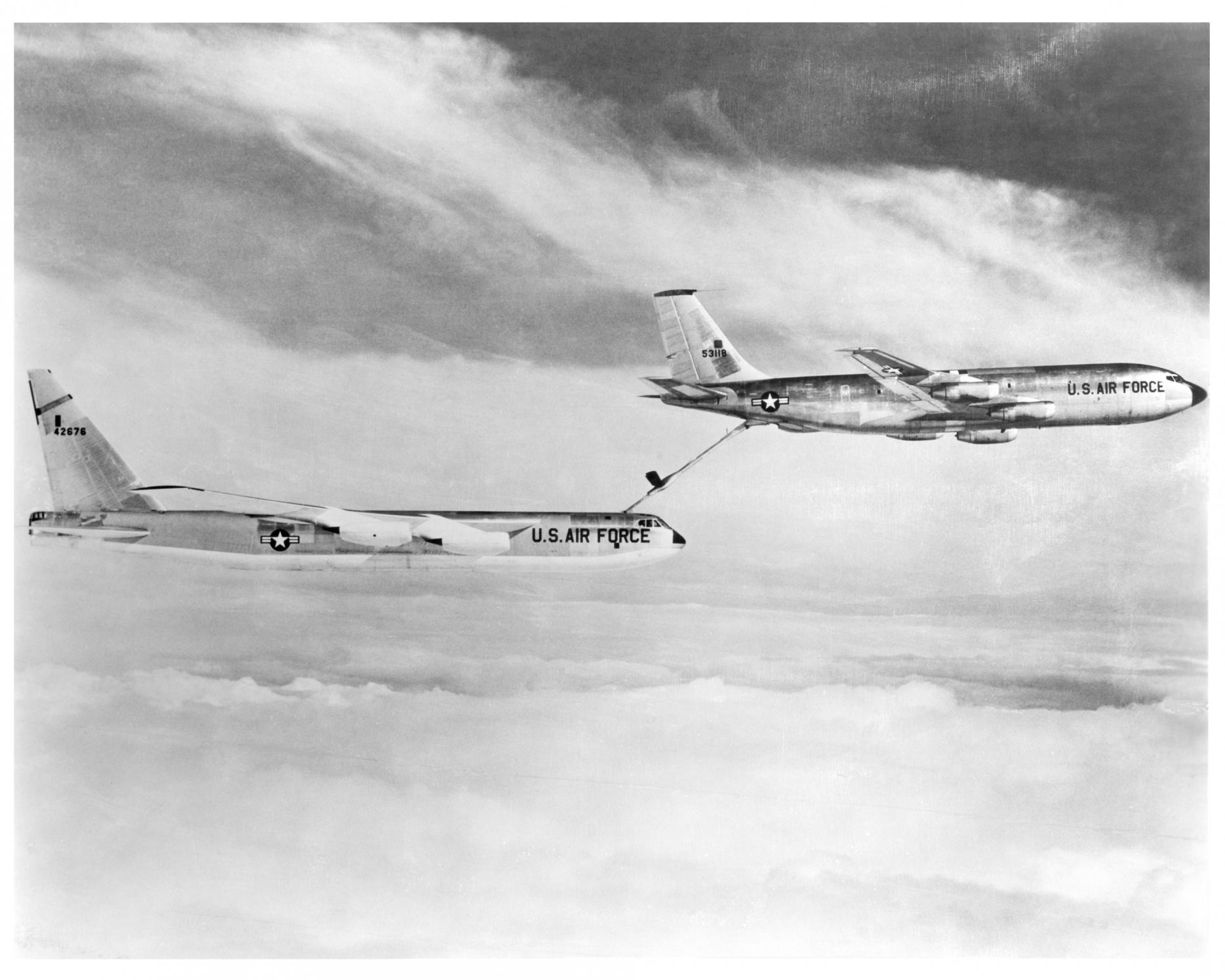

In 1987 I think there were only two large aircraft types doing "authorized" air shows, one was from the KC-10 tanker school house and the other was my squadron, flying the Boeing 747 (E-4B). The Commander in Chief of the Strategic Air Command, General John Chain, thought it would be pretty neat if his boys had an aerial demonstration team of the caliber of the Thunderbirds. And so the Thunderhawks were born. It was to be a KC-135A tanker and a B-52 bomber, both from Fairchild Air Force Base. Since my squadron had an airshow pilot, we were invited to see the Thunderhawks do a trial run in front of General Chain. The show involved a fly by of the KC-135A refueling the B-52 during a pass over the runway at around 500 feet. That was scary enough. But there was more.

After passing "Airshow Center," the bomber disconnected and rolled into a steep bank turn while the tanker rolled steeply in the opposite direction. I have about two years experience in the KC-135A and thought it would have taken full aileron deflection to get that beast of an airplane to roll so quickly. After both aircraft completed their 360° turns, they ended up back in formation, right where they started.

A member of the general's staff asked our squadron's airshow pilot what he thought. He told the staff member that he thought the demonstration looked dangerous. We found out the next week that General Chain approved the demonstration but asked that the pilots "tighten it up."

- At 1:20 p.m. on Friday, March 13, 1987, a B-52 Stratofortress and a KC-135 Stratotanker took off from Fairchild Air Force Base (AFB) to practice aerial maneuvers for a 15-minute air show scheduled on Sunday, May 17, Fairchild's annual Aerospace Day. The show was to be the debut of a new aerobatics team dubbed the Thunderhawks, the brainchild of General John T. Chain Jr., commander-in-chief of the Strategic Air Command (SAC). Its purpose was to demonstrate the capabilities of SAC’s large aircraft through a series of exciting routines that included a low-level refueling simulation, high-bank turns, and flybys down the runway. Colonel Thomas J. Harris, commander of the 92nd Bombardment Wing at Fairchild AFB had been assigned the responsibility for the Thunderhawks’ creation and development in December 1986.

- The KC-135A-BN Stratotanker, No. 60-0361, had three instructor pilots aboard the aircraft: Lieutenant Colonel Michael W. Cornett, Captain Christopher Chapman, and Captain Frank B. Johnson. But no one on the ground at Fairchild knew who was actually in command of the aircraft when it took off. Also on board plane were two navigators, Captain James W. Litzinger and First Lieutenant Mark L. Meyers, and refueling-boom operator, Staff Sergeant Rodney S. Erks.

- The KC-135 had just taken off from runway 23, in tandem with the B-52, and was executing a steep left-hand turn when it suddenly rolled from an intended 45-degree bank to almost 90 degrees, stalling the two engines on the left wing. The crew managed to level the aircraft, but it was flying too low and slow to recover. The plane crashed landed in an open area north of the flightline, behind three large hangars, narrowly missing the base’s bombing and refueling squadron offices. It skidded through a security fence, across an access road, and killed Senior Master Sergeant Paul W. Hamilton, a member of the Thunderhawks on his day-off from flying, who was sitting in his car watching. The aircraft traveled for another 200 yards, then hit an unmanned weather radar tower and burst into flames. During the journey, the tail section separated from the fuselage as well as the wings, engines, and wheels. One wing, ripped off by the collision with the radar tower, landed 50 yards beyond the burning wreckage.

- On Friday, June 12, 1987, the Air Force Accident Investigation Board released an official report concluding the crash of the KC-135, which happened just after takeoff, was caused by wake turbulence from the B-52 with which it was to practice aerial stunts. The tanker was behind and at a slight angle to the bomber’s flight path, overshot its turning point and started a 45-degree roll to the left to get back on course. When the KC-135 inadvertently hit the B-52’s wake, the plane suddenly rolled to nearly 90 degrees and was flying too low and too slow to enable a recovery. According to the flight plan, the KC-135, with refueling boom extended, was to execute a pass at approximately 500 feet, with the B-52 following at 200 feet. During the demonstration, the tanker was never intended to fly lower than 100 feet above the flight path of the bomber.

- As a result of the KC-135 crash at Fairchild AFB, the Air Force canceled all scheduled SAC aerial demonstration programs and the Thunderhawks team was officially disbanded. The Air Force Secretary, Edward C. Aldridge Jr. promised Congress it would not to use heavy aircraft, such as bombers and tankers, in risky maneuvers for air shows.

Source: History Link

We heard that SAC added a warning to the KC-135A flight manual that said you should never fully deflect a flight control because once you've done that, you've got nothing left. I thought that was hilariously obvious.

Our squadron carried on as before, doing airshows at our base and a few others. The normal routine was to takeoff, do a high-speed pass at a "low altitude," do a climbing 90° turn using about 45° of bank, reverse the roll, and come back for a low speed pass with the gear and all the flaps extended, followed by another 90°/270° turn and a maximum effort full stop. All of these airshows were performed by our pilot designated to do functional check flights (FCFs). When he left, I took his position and airshow responsibilities. During my one and only checkout flight, I asked him how low I should fly during the high speed pass. "Get as low as you can without scaring yourself." I tended to do this at 30 feet, 300 knots.

I did these for a few years but I couldn't make one particular airshow. The squadron sent one of our highly experienced instructor pilots who nearly lost the airplane during one of the 90°/270° turns. He got the 45° of bank just right on the initial roll away from the runway, but he overshot on the reversal and nearly got to 90°. The nose dropped sharply but he managed to save it. He leveled the wings just a couple of hundred feet and flew right over the airshow crowd, a cardinal sin in an airshow. The squadron commander removed the pilot's airshow privileges and called it a day.

So I continued along doing the airshows, thinking I was doing everything right, having never scared myself. That is until one day I did. During one of my 90°/270° maneuvers I felt the ailerons hit their stop. I had nothing left. Still, I didn't exceed the 45° bank target and nobody noticed. "Nice job, sir," was about the only feedback I got on these airshows. But I realized that over the years I had slowly but surely pushed myself to the point I had nothing left. I gave up my airshow pilot duties that year and never looked back.

3

Some advice

So we have three examples of how things can get out of control. In the case of the Falcon, everything seemed to go well and all the participants are pleased with themselves. In the case of the tanker airshow, everyone is dead and in the end their only purpose was to serve as a lesson for the rest of us of what not to do. Finally, in the case of my airshow experience, nobody was the wiser and knew about my transgression, but of course they do now. I think all three examples could have benefited by a better ROE.

There is a time tested law of military conflict that says:

"No plan survives the enemy."

Battle is fluid and you need to have a robust set of rules, called "Rules of Engagement," or ROE. The same holds true for flying an airshow or doing any kind of flying where you are operating near the edge of your normal flight envelope. If you set up your ROE from your desk chair, compare those ROE to others in similar situations, and have those ROE vetted by sane individuals, you are less likely to come up with something in the stupid category (the case of the tanker airshow). Then if you set those ROE in stone and have the discipline to not deviate from them, you can avoid intentional noncompliance when your goals are unachievable (the case of the Falcon record attempt). Finally, you need to revisit those ROE and have the participants evaluated now and then to avoid the case of a cocky and overconfident pilot flying by his or her own set of rules (the case of my too aggressive roll rate).

- Have your best experts establish procedures, operational limits, and "knock it off" criteria ahead of time. Start the process with "why?" before considering "how?" Then consider "what if?" to establish points where the entire endeavor needs to be aborted. These become your Rules of Engagement (ROE).

- Pass the ROE amongst your most capable and trusted peers. Consider contacts from your training vendor and aircraft manufacturer. You may be surprised that what you are attempting to do was already attempted before. If so, it may be that your attempt is unnecessary or foolhardy.

- Get leadership's buy in.

- Ensure all participants understand the ROE, that the ROE has been vetted, and that leadership is in on it too.

When you build your ROE, remember that not every problem involves danger; some are simply misuses of company assets. Years ago a company I worked for had an entire flight department fired because the crew took a fairly straightforward request from the owner too far. This was a fantastic flight department flying a great schedule all over the world in a Challenger 604. Each year everyone was treated to a bonus equal to their salary. When they upgraded to a Global Express, the owner asked the pilots to put some hours on the airplane for a week. The flight department decided to load up with husbands and wives, fly to Maui, and parked the airplane for a week. They came back to pink slips.

That crew could have saved their jobs with a good ROE:

- Purpose (the "why?") — gain experience with the new type, discover any problems from the manufacturing process, learn how to operate the airplane from initial start up to putting it away for the night.

- Procedure (the "how?") — fly to locations where type-relevant maintenance is available, preferably duplicating normal operations on the previous type, and at a tempo that maximizes practice while minimizing cost.

- Limitations (the "what if?") — observe VFR weather minimums until the pilots at the controls have a minimum of three takeoffs, approaches, and landings. Observe "high minimum captain" minimums until the hours minimums in company regulations are met. Do not allow Minimum Equipment List write offs without the director of aviation's approval.

- Abort criteria (the "knock it off") — if presented with a "we don't know what to do" situation, fly the airplane, request ATC assistance, contact the manufacturer, land the airplane. Regroup with management for the need to adjust the ROE and come up with a new plan.

4

Careless or reckless operation

I used to fly with a pilot years ago who greeted any news reports of what I call "stupid pilot tricks" with the answer, "I've done worse and bragged about it." In case you are in that camp about the Falcon 8X story, here are some things to ponder.

Threshold Crossing Height

Runway 21 at KSMO is serviced by a PAPI set to 3.5° and listening to the RAAS callouts it is pretty obvious they were below that. The regulation talks about remaining above a VASI but I think any FAA inspector would be well within his or her rights saying that for the purpose of 14 CFR 91.129, a PAPI is the equivalent of a VASI:

Each pilot operating an airplane approaching to land on a runway served by a visual approach slope indicator must maintain an altitude at or above the glide path until a lower altitude is necessary for a safe landing.

Source: 14 CFR, §91.129(e)(3)

Oxygen

To those that say "nobody follows these rules," I have first-hand evidence that is wrong. (My flight department follows these rules and I hear from others that do.)

(b) Pressurized cabin aircraft. (1) No person may operate a civil aircraft of U.S. registry with a pressurized cabin—

(ii) At flight altitudes above flight level 350 unless one pilot at the controls of the airplane is wearing and using an oxygen mask that is secured and sealed and that either supplies oxygen at all times or automatically supplies oxygen whenever the cabin pressure altitude of the airplane exceeds 14,000 feet (MSL), except that the one pilot need not wear and use an oxygen mask while at or below flight level 410 if there are two pilots at the controls and each pilot has a quick-donning type of oxygen mask that can be placed on the face with one hand from the ready position within 5 seconds, supplying oxygen and properly secured and sealed.

Source: 14 CFR 91, §91.211

Takeoff distance, takeoff with a tailwind, "going for it" and "Definite Zero G moments"

I agree these items can be subjective and if you are of the type to argue that you should be able to use every last inch of runway, takeoff with up to 10 knots of tailwind, and fly at zero G because the book says you can, I will say go in peace and I wish you well.

Careless or reckless operation

Finally I would add the following to a flight that operated on the margins of safety for the sake of these kinds of records:

(a) Aircraft operations for the purpose of air navigation. No person may operate an aircraft in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.

(b) Aircraft operations other than for the purpose of air navigation. No person may operate an aircraft, other than for the purpose of air navigation, on any part of the surface of an airport used by aircraft for air commerce (including areas used by those aircraft for receiving or discharging persons or cargo), in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.

Source: 14 CFR 91, §91.13

5

Mailbag

James,

Really appreciate all you've done with this website. Phenomenal information! Love the mathematical aspect of your explanations. Too bad so many pilots are math averse (You'd think a discussion on W&B and %MAC is Differential Equations).

Anyway, quick story. I started a new job last week, Part 135. Nothing special (as you'll see) but went in with high hopes but a cautious attitude. On day 4 of basic indoc the Chief Pilot told a story about a "Rockstar" departure in a Learjet. You know, the pop off the ground, retract gear, flaps, accelerate, pull up abruptly at the end of the runway. The crew did this WITH pax on board, at the request of the husband. The maneuver was abrupt enough the wife was crying. Nice, huh? Anyway, the Chief caught himself (slightly) and attempted to walk the story back a bit and said this wasn't a "Normal Maneuver," we would only do this with repeat customers we knew and were familiar with. Huh?? Wow.

I sent in my resignation letter yesterday. Only there one week. No point in going a step further. Unknown if I'll get paid for my week there or my expenses. Doesn't really matter.

Remembered the article you wrote (sorry, don't know if it was on 7700 or in B&CA, enjoy both very much) on this type of flying. Was stunned to hear the story openly told to New Hires. By the Chief.

Signed, anonymous

Dear Anonymous,

On the surface this is a disheartening story but I take a lot of encouragement from it. The fact there are pilots out there, like you, willing to put integrity over pay check says a lot about our industry. Thank you for standing up to this kind of intentional noncompliance. I hope your example provided that company an opportunity for some soul searching.

James

References

(Source material)

14 CFR 91, Title 14: Aeronautics and Space, General Operating and Flight Rules, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation

U.S. Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker crashes at Fairchild Air Force Base, killing seven airmen, on March 13, 1987,, https://www.historylink.org/File/8871, Posted 12/20/2008