"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Seven.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-06-26

By 1981 I had nearly two years experience flying jets as an Air Force pilot and had immersed myself in all things aviation. We had a few deaths during my year of pilot training and the KC-135A fleet continued to average about two crashes a year since then. I knew, very early on, that gravity always wins.

I had never paid much attention to the term "windshear" until watching an interview on television of a Flying Tiger Line captain who nearly bought the farm when he experienced it in 1975. We pilots now understand the sudden change in wind speed and direction very well, given those that have succumbed to it since the widespread use of flight data recorders.

1

"You got yer hands full, buddy!"

1981

When I first got to Loring I was assigned to crew S-105, that is, "Select Crew 105." We were nothing special, that meant. The good guys were on "E" crews. I had to take a check ride with the squadron commander and after that got one of those "you can never repeat this" briefings. The captain was prone to doing stupid things and my job was to stop him. After six months of that I was assigned to the Leper crew, with the promise that if I survived, I would get a good crew. I did survive, and they assigned me to Major Billy D, a "staff retread." Major Billy was one of those guys who fled the cockpit as soon as he could to the staff, but now he had to put in a few more years in the cockpit to make his flying gates, arbitrary numbers you had to meet in order to continue drawing flight pay.

Major Billy was a political animal. When he showed up on base he had never lived in a northern climate, never smoked, never hunted. After a day in the squadron ready room, talking with his fellow aircraft commanders, Billy fit right in. He bought a snow mobile, started chomping on stogies, and bought himself a rifle. He never got a check ride with the squadron commander; he just got his keys to crew S-108.

The best thing about Major Billy was that he knew his limitations. He was overly cautious, which at first bugged me because we had a low likelihood of being assigned an airplane and actually making it off the ground. "I don't like the looks of number three," he would say, and we would sit on the ground working with maintenance until it was too late and a spare aircraft took our mission. At first it infuriated me. But after a few close calls in the air, I decided being stuck on the ground might actually beat being in the air with him. After my first actual trips away from base with Major Billy, I realized his biggest issue was being away from his wife. He talked incessantly about missing her; it was embarrassing. Whether it was an abundance of caution or a reluctance to spend the night away from his own pillow, Major Billy didn't like being on trips. In any case, I wasn't getting a lot of flying time working for Major Billy.

Still, I needed the flying time to upgrade and find my way out of Northern Maine. So when we got tasked to airline down to Montgomery, Alabama to pick up a depot bird, I was ready to go. These depot deliveries were a bit of a pain. You showed up, waited for the depot boys to finally release the airplane they had been working on for six months, and then you flew home. The rules said the return flight had to be done in daylight and the captain had to do the flying. It wasn't a good deal for the copilot. But at least it was flying.

"What did they do to the airplane," I asked the operations officer when he handed me the orders.

"I don't know, lieutenant. Just pick up the damned airplane and bring it home."

The airline trip to Montgomery was pleasant enough. The hotel was passable and had a working room air conditioner and a television that got five channels, two more than what we got up in northern Aroostook County, Maine. I flipped through the channels and stopped on the shot of an airline captain with the obligatory four silver stripes on this shoulders talking with a model of a cargo DC-8 beside him. He had a grim look to his face and was talking about the scariest landing of his life.

"We were carrying a load of cattle," he said, "each in a small pen to keep them from moving about. You can't have cattle walking about the length of the airplane, the CG change would overwhelm the airplane's horizontal stabilizer."

Cows and center of gravity? I was hooked.

"So each cow is in his own pen, but they are standing. Or they were standing. We hit the runway so hard that all twenty-five cows broke each of their four legs. They all had to be destroyed." The captain fought back tears.

He went on to describe his DC-8, an older cargo version which had just been upgraded with an inertial navigation system. He had never used one before, but was fascinated by its ability to report the airplane's ground speed instantaneously. I had never seen an INS at this point in my short career, but I understood the principles. Three spinning gyroscopes equipped with force meters could detect aircraft movement. You ended up with very accurate heading and speed information.

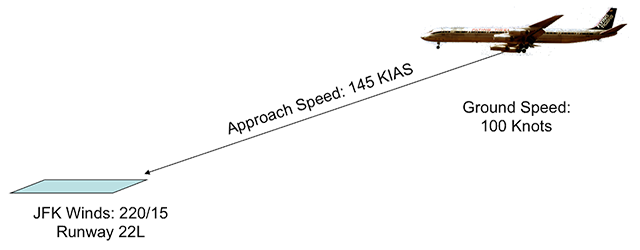

"We were on approach to runway two-two-left at JFK," he said, "and the copilot and I bugged 145 on our airspeed indicators. That number was a little higher than normal, but we were heavy. Everything seemed normal, but the INS said our ground speed was only 100 knots. I wondered how that was possible. The tower reported the winds were right down the runway at 15 knots. It seemed to me we were missing 30 knots."

Sometimes those electronic gizmos don't work so well, I thought.

"Well," he continued, "at least it was right down the runway. So I continued what I was doing, keeping the airplane flying down the ILS." This airline captain appeared to be in his fifties, was very well spoken, and had a grave calm about him. "Right around 300 feet, I felt the airplane start to sink. The airspeed indicator was falling fast. I pushed the throttles forward a little at first, and then a lot. By the time we were at fifty feet I had them to the firewall but it was too late. I managed to get us to the first inch of the overrun, but we hit hard."

The airplane was heavily damaged, but flew again. The cattle didn't make it.

"I've done a lot of soul searching after that," the captain said, "and I started to wonder about those missing 30 knots. What if the wind that day was greater a few hundred feet up than it was on the surface? When we lost all that headwind, wouldn't have that caused the sudden sinking?"

In 1975 this was revolutionary thought. I've heard that some pilots and aviation groups were thinking about it, but it wasn't yet widespread knowledge.

"So I thought," the captain concluded, "if you know the magnitude of your headwind on the runway, and if you know the magnitude of your headwind in the air, why not come up with a minimum acceptable ground speed on approach?"

It was brilliant. He had conveyed a method of beating this kind of windshear. I logged it all away for future use.

The next morning we showed up at the plant at 0900, just like the orders said, and were told our KC-135A would be ready soon. They let us onto the airplane about 1200, but the paperwork wasn't ready so we had to wait. They let me into the cockpit to stow my gear and I spotted two new boxes, one on each side of the cockpit. I recognized them immediately, inertial navigation systems. In a box in the cargo compartment I found a 100-page instruction manual and while we waited, I read. It was good stuff.

By the time the paperwork was done it was 1500. "Major, we have to land in the daylight," I half asked, half stated, "don't we?"

"That's been waived," Major Billy said, "we're going home tonight."

I hopped into the right seat and turned the INS to "align," and punched in the latitude and longitude. As the inertials started to count down their alignment I could hardly wait.

"Hey," Major Billy said as he entered the cockpit, "we haven't been trained to use those, turn them off."

"I read the manual," I said, "I want to use it."

Major Billy said nothing, so I left the thing on.

By the time we made it off the ground, it was already pretty late. The INS were counting up the latitude and longitude as we made our way northeast. I didn't figure out the waypoint system yet, so all I had was the orange glow of the lat/long on one side of the cockpit, and an instantaneous readout of our magnetic course and ground speed on the other. Still, it was pretty cosmic.

About an hour south of Loring, I got the weather via HF phone patch. "It sounds bad," I told Major Billy. "They are saying the winds are 350 at 40, ceiling is 200 feet, right at minimums. Forty knots of wind, I don't think I've ever seen that before."

Major Billy said nothing. He just sat in his pilot's seat thinking. Finally he keyed the interphone. "I think it's time for some copilot training tonight, you want the landing co?"

"Sure!" I knew the rule said the pilot had to fly the aircraft from takeoff to landing on these depot deliveries, but somehow his idea sounded better to me. As we got closer the automated weather report started coming in. The winds were still reported to be down the runway but now they were up to 50 knots.

The command post frequency, UHF 311, was usually reserved for the pilot. But I toggled the mike anyway. "Has anyone landed recently?" I asked.

"Just one," they reported, "another tanker. He's taxiing in right now."

I got permission to speak to that tanker directly. It was Capt Paul Church, a good guy. "How was the approach and landing with all that wind," I asked.

"You gotcher hands full, buddy," he said, "those winds are pretty strong tonight."

I wasn't really sure that added anything to my knowledge. Fifty knots of wind! At least they were right down the runway, no crosswind controls required. But fifty knots!

Around 5,000 feet, turning south to align with the instrument landing system, I was at 250 knots getting ready to slow for the landing gear. My normal timing cues were not working. It was taking forever to get to the glide slope intercept point.

Why were things happening in slow motion? I looked down to my INS and saw the answer: our ground speed was only 110 knots! How was this possible? I was still cruising along at 250. I didn't know the INS could give me a wind readout—I hadn't read that far into the manual—but if I was indicating 250 knots and my ground speed was 110, the winds at 5,000 feet must have been 140 knots. I was going to lose 90 knots somewhere between 5,000 feet and the runway.

The night before the airline captain on television said you should never let your ground speed get below the expected ground speed crossing the runway threshold. What does that mean? I couldn't put it all together while hand flying the airplane with all that wind.

Finally at glide slope intercept I extended the landing gear and let the airspeed decay to 200 knots. My ground speed was only 60 knots. It should have been 150 knots based on the tower-reported winds. What would that DC-8 captain have done? He would have added the difference, that's what.

I couldn't add 90 knots to my speed; I wouldn't be able to get the flaps down. The limiting speed for our full complement of flaps was 180 knots. Mother SAC wouldn't allow us to land with anything less than all the flaps unless there was an emergency situation. This wasn't an emergency, was it?

I decided to fly the approach and landing at 180 knots, 45 knots faster than normal. That should be enough. Major Billy said nothing about my hyper approach speed.

I was stable on glide path and on course, 180 knots, about four hundred feet above the treetops. At 300 feet I spotted the first set of approach lights and then felt a sinking sensation. The airspeed indicator was unwinding so fast I thought it was broken. Then, I fire-walled all four engines.

We continued to drop but the airspeed slowed its plummet and as the wheels kissed the runway the airspeed stopped at 120 knots. We were on the ground so I pulled all four throttles to idle.

We were silent in the cockpit until the navigator keyed his interphone mike.

"Copilot, nav."

"Go ahead."

"When my son is born, I'm naming him after you."

I thought about that landing for a long time and tried to quantify the method that saved our collective hides that night. I decided on "minimum acceptable ground speed on final to account for wind discrepancies." It didn't roll off the tongue, did it? The crux of the technique was to subtract tower winds from INS winds, add that to your expected indicated speed over the runway threshold, and then to use that as your minimum acceptable ground speed on final. The technique was good, but putting the technique into words needed practice. Somebody helped me out. . .

Three years later, while at the Air Force Safety Officer's Course, I found a C-141 flight manual that detailed a brand new idea when combating windshear. They called it the "Minimum Acceptable VREF" technique.

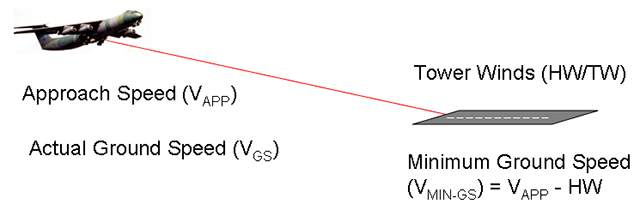

Minimum VREF is found by subtracting the reported runway headwind from the aircraft's expect speed crossing the threshold. If ground speed on approach goes below Min-VREF, add the difference to approach speed. If ground speed on approach goes above Min-VREF, fly target approach speed and expect a tendency to balloon and land long at best, a microburst at worst.

Years later the Air Force abandoned the technique, fearing the math would overwhelm most pilots and the safer course would be to preach "when in doubt, go around." Of course, military pilots are trained to have no doubts. I've kept the technique and it has saved me many more times.

2

Postscript

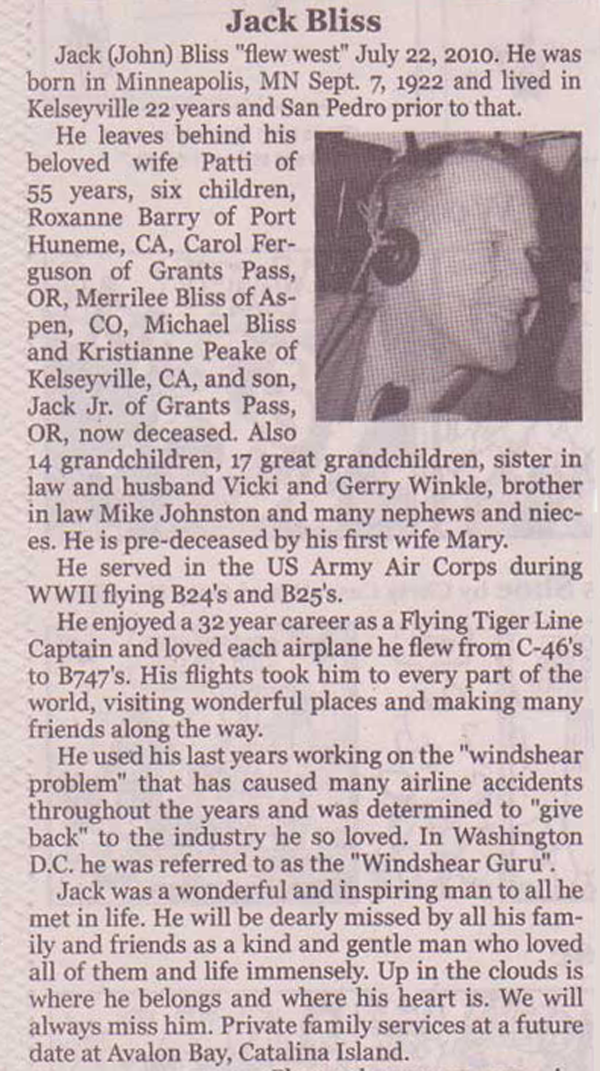

I've been telling this story for thirty years now, perhaps with a tinge of regret. Regret that I never knew who that DC-8 captain was, I wanted very much to contact him one day to thank him. I only caught the tail end of the TV show, I never caught his name or the airline he was flying for. Truth is, I didn't realize just how important this information was until the next day when it saved my life and that of my crew. Over the years I've made efforts, but nobody seemed to know.

Then, in 2015, a magazine I write for asked me to write an article looking at windshear, how we've progressed over the years. So I pulled up the NTSB aviation accident report on Eastern Air Lines 66 and read about a Flying Tiger Line DC-8 captain who landed just prior who worried about his ground speed and pleaded with ground control to change the active runway. I thought this might be the guy. I called the Flying Tiger Line Alumni Association and found out it was him, Captain Jack Bliss.

I don't often use my real name on this website, but this is very important to me. So here is the email answer I got . . .

Hi James:

My name is George Gewehr and I’m the FTL historian and ex President of the association. The Captain you are asking about was Jack Bliss. He has flown west several years back, I’m thinking six years ago. If he were still here he would have loved to have heard your story. I have a news paper clipping of him with an attached article to it. Just coincidentally I was at Jfk when he landed. I had arrived from the west coast about forty minutes before Jack had landed. I had passed the very storm over the Sparta VOR that later hit JFK. When we were on the ground we were in the Tiger building and it hit us. It was a HELL of a thunder storm and moving very fast. I was sitting in our operations office when his copilot walked in and sat down next to me. I was startled to see him and asked him, “Where in hell did you come from” He said he just landed with Jack Bliss and that Eastern Airlines had crashed behind them. Jack had a load of live cattle on board his airplane. Needless to say the airport was closed for a while until JFK could sort things out. Hope that helps you in your search.

Sincerely, George Gewehr

I think it is very important for pilots to have mentors and aviation heroes. It gives us something to aspire to and something to inspire us to learn and become better than we are. I've never met my mentor, but I will never forget him either.