"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Ten.

— James Albright

Updated:

2016-12-15

Every now and then I get a question from a reader that causes an instant reaction, a moment of reflection, some pen to paper, and then a circle back to the initial answer. Most of these are more psychological than technical, and this one is no exception.

Thinking about it, I realize now that throughout it all my focus has been on the "now" and not so much the "to be." I always said that if you take care of the present, the future takes care of itself. Or, more conventionally, it is the journey, not the destination, that gives life meaning. I hope what follows will provoke some introspection of your own.

A question of balance

2016

James,

Aviation has been my passion since I was a young child, and I aspire to learn all that I can not just for my own knowledge and wisdom, but so that I can lead by passing it on to others. Since this quest is very time-consuming and labor-intensive, it can be difficult to find a balance with life outside of aviation.

I have a beautiful wife, three young children, a wonderful extended family, and church responsibilities. You've mentioned the "Lovely Mrs." and your children in some of your posts. As you raised your young family and searched for knowledge (The Meaning of It All), how were you able to find a balance with your other life responsibilities? How did you spend your time and prioritize your attention? What did you do well and what could you have done better? I apologize if you have addressed these questions already in other posts and I have not come across them yet. If so, would you point me to them? If not, perhaps other aviators like me would appreciate your insight on this subject so that we can better reach our potential not only as pilots, but as leaders, husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, and just good men and women in general.

Thank you, again, for your dedication to your work. I look forward to hearing back from you.

Sincerely,

A Pilot, Husband, and Father

CE-750

Dear Pilot, Husband, and Father,

My first reaction to “how did you find a balance” was to say, “I didn’t.” But I suppose that can’t be true. As you may have noticed with my articles in Business & Commercial Aviation magazine, I’ve started with a background in the technical side of aviation but have gravitated towards the psychological aspects. It is our human nature, after all, that seems to cause most accidents. So perhaps this is a good topic to dive into. So here goes . . .

How were you able to find a balance with your other life responsibilities?

The Lovely Mrs. and I first met when we were in high school, just 15 years of age. The Vietnam War was winding to an end; I had a 1-A draft card (meaning I was ripe for the taking and could very soon find myself carrying a rifle for the Army). I had uncertain hopes and aspirations.

My dad was an officer in the Navy, commanding an intelligence gathering ship off the coast of North Vietnam. The USS Advance was, by outward appearances, a minesweeper. But it was actually a spy ship.

He was a much smarter man than me; he somehow convinced me that he was too poor to send me to college, so I had to find my own way. The draft came to an end during my senior year and I ended up with an Air Force scholarship to Purdue University and a slot to Air Force pilot training.

We got married at 19 and I showed up at pilot training at 22. During that year we would lose four pilots, including our next-door neighbor. My closest call was losing an engine at V-1 in the supersonic T-38. (More about that: T-38 Engine Failure at V1 - Duck Soup.) The Air Force has since had a change of heart about these things. These days such a death rate would cause a full stop on all flying and investigation to correct things. Back then, it was just a part of doing business. So The Lovely Mrs. and I learned just how unforgiving aviation could be.

My first assignment after pilot training was to fly the KC-135A tanker. That oldest version of the tanker was called a “water wagon” because its engines needed over 5,000 pounds of distilled water to augment the thrust, just to get off the ground. (More about that: Water Injection.) It was a dangerous airplane. By 1979 we had crashed 54 of them. That’s almost two every year since it started flying. (That change of heart I talked about happened in the early nineties and it solved everything. Since 1993 there have “only” been three subsequent crashes.) At Loring we lost one, but there were more than a few close calls. My closest was the engine failure in Guam that I wrote about in Flight Lessons 1: Basic Flight. But there were others.

Three years later I went to the Air Force Flight Safety Officer Course and learned how to be an accident investigator. In retrospect, that is when I started applying a litmus test to everything I did in aviation: is this safe? Of course I strayed from this path for a brief time, as I’ve detailed in Flight Lessons 3: Experience. But that litmus test has been with me for a very long time.

We were to lose more squadron mates over the years and that, I suppose, gives one focus on what is important and what isn’t. After I retired from the Air Force a friend asked The Lovely Mrs. how she was able to keep her sanity knowing I spent all those years in an environment where people didn’t always come home alive from a flight. She said she tried very hard not to think about it. She knew that wearing the uniform was service to country, and that was my priority.

So back to your question of balance and the answer I first offered tongue in cheek. I think I didn’t find a balance because there couldn’t be a balance. I often say safety is not an option; it is a prerequisite. In Latin, it is the sine qua non, “without this, nothing.”

“Safety First!” is one of those slogans that just about everyone preaches, but very few actually practice. The safest way to fly is to never leave the ground. But of course we have to leave the ground. So the quest here is to do that while stacking the odds in our favor. That is why it is so important to study, to train, and to take this flying thing rather seriously. I think being a pilot can be likened to being a pro golfer. First, you have to get the mechanics down. The pilot’s stick and rudder skills are like the golfer’s quest for the repeatable swing. But what makes a golfer great is the ability to have a quiet confidence and a settled brain that tunes out all distractions during that swing. We as pilots need to have the confidence that we are fully prepared for the task at hand. So you study, you train, and you prepare until you are confident that you have studied, trained, and prepared enough. At that point, you are free to get on with other aspects of your life.

How did you spend your time and prioritize your attention?

So let’s bring this discussion from the military to the civilian and talk about an experienced pilot seeking that balance and how, as you say, to prioritize his or her attention. I call this the need to adjust focus.

Let’s say you are graduating from one model of airplane to the next one up the rung. Say from a Citation V to a Citation X, a Challenger to a Global Express, or a GIV to a G550. But you also have responsibilities to your family, your friends, and your community. Where does your focus belong?

In one of my books The Lovely Mrs. warns the kids, “Daddy’s mind is going to be someplace else for a while.” She further tells me to not worry about them until I have the new airplane mastered. When I seem surprised she says, “You are no use to us dead.”

While that seems overly dramatic, isn’t it true? Looking at aviation mishap databases, I see there have been 3 crashes of the Citation X. In my Gulfstream world the results are even worse.

When you first jump into that new airplane, learning everything you need to know has to be your primary focus. Without this, nothing. But learning takes time and there is only so much learning your brain can do in the short term. My kids were used to me sequestering myself with study materials until I came out and said, “My brain is full.” At that point, doing something else was actually helpful.

Once you are comfortable with your level of knowledge, you must continue the pursuit just to maintain that level of safety and to avoid complacency. I think the key word is “comfortable.” Do you feel you’ve done enough? If the answer is yes, then your focus can (and should) shift to other things.

You cannot neglect your family for two reasons. First, paying attention to your family is the right thing to do. But it is also important to calm your mind to allow you to focus on aviation when you have to. Military pilots call this compartmentalization, but we might exaggerate our ability to compartmentalize. The talking points are this. I have my “dad hat” on and I focus on helping the kids with their homework, a little play time, dinner, and off to bed. The next morning, I send them off to school. Then I put on my “steely-eyed aviator hat” and all that dad stuff leaves my consciousness so I can completely focus on flying. When the engine quits or the cabin fills with smoke, I am not burdened with any of the dad stuff. I am the steely-eyed aviator, after all.

Truth be told, compartmentalization is easier for some than others. The best way to be able to compartmentalize is to be comfortable that you have done enough in all your responsibilities.

So now we can talk about prioritization. I suspect most aviators have the same priorities, but maybe not. So here are mine: family first, aviation second. But how can that be? Aren’t I the pilot who seems to spend all my time working on all things aviation? Let me walk you through this. I make my living flying airplanes and writing about aviation. That puts food on the table and has put two kids through college and one of those through dental school. I’ve been doing this for 38 years now. Along the way, I’ve made a few decisions that would seem counter-intuitive. I didn’t go to the airlines. I’ve turned down offers to fly other airplanes. I’ve elected to stay in a part of the country that is too cold for my liking. Being a professional pilot, then, is how I provide for my family.

That decision – being a professional pilot – is done. Now I need to be a safe pilot or one day I won’t be coming home and that does the family absolutely no good. So I put as much effort as needed to make that happen. Once that level is achieved, I can place my focus on the family directly. But the decision making process doesn’t end there.

When the next opportunity comes, I need to judge its impact on the big picture. Let’s say I am offered a job in a warmer climate flying the next generation of airplane that has been on my wish list for a few years. More income helps the family, but they may or may not want to relocate. The thought of learning a new airplane is exciting, but it pushes me back into having to sequester myself for months or even years until my comfort level with the airplane and new operation is where I want it to be. Since my priority is my family, I have to think about the prospects of increased income versus our physical relocation and my mental relocation. Daddy’s mind will be elsewhere for a while.

I am at the stage of life where many of my family constraints are easing. My son and daughter are both grown adults, providing for themselves as productive members of society. The Lovely Mrs. has retired from nursing and is now one-half of a therapy dog team. She likes to talk about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and the self-actualization stage where one gives back to the community. She is doing that at local hospitals and rest homes. She says I am doing that through the website and my writing.

What did you do well and what could you have done better?

As the great philosopher Frank Sinatra once said, “Regrets, I’ve had a few.”

I’m sure I could have been a better father. The Lovely Mrs. and I often say that: parents begin as novices, learn along the way, and by the time they know what they are doing, the job is done. That being said, both kids are successful, happy, and on good terms with us. So we must have done something right.

As for aviation, I’ve had 18 reportable incidents where engines quit, things caught on fire, or something just simply failed. I managed to get the airplane onto the ground each time without hurting anyone. I also hope that I managed to make others around me safer by setting an example, by direct instruction, and by writing.

The answer to your question

That brings us back to my first answer to your question, “How did you find balance?” In short, I didn’t. The decision to become a professional pilot happens more than once. From that first time to every instance where you elect to remain in the profession, you are deciding to give up the balance. Sine qua non. Because your profession can be dangerous, you need to prioritize achieving a level of safety that you are comfortable with before turning your focus to anything else.

This isn’t placing job over family; this is focusing on the job because of family.

I hope that answers your question. It is my answer; it may not be yours. But I hope it helps you discover the answer that is right for you.

James

Postscript

One last word of advice

Years ago I was in an eight pilot flight department where one of the pilots was having a bit of a rough patch with his wife but seemed confident they could work it out. I told him that it was remarkable that in every squadron and flight department I had ever been a part of many of the pilots had been divorced at least once. And it was even more remarkable that in our flight department, no one had been divorced.

The pilots in the room with me all looked at me dumbfounded. "Everyone of us has been divorced, except you."

Well they fooled me, they all seemed perfectly happy. And that was the lesson. Being a professional pilot can place quite a strain on a marriage and it quite often goes better the second time around because the new spouse knows what he or she is getting into. The first time you and your spouse may not have known the stakes were so high, or you may have downplayed them.

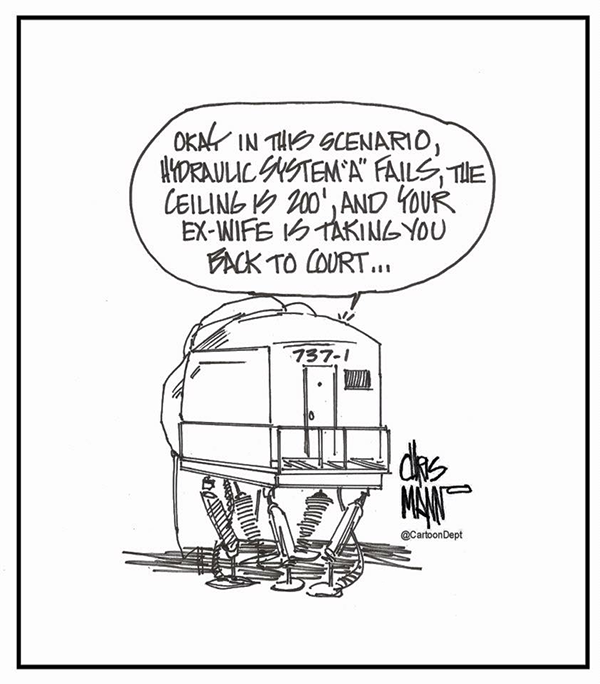

Regardless of which number marriage you are on, it behooves you to include your spouse in the trials and tribulations of what you are going through. If you can get them into the simulator with you, perhaps they will gain a new respect of just what is at stake. But even if you can't do that, a little honesty about just how hard you have to peddle just to keep up can go a long way.

The Lovely Mrs. has met a few of my fallen comrades and that can be sobering. But even without that, she knows how much effort I pour into this endeavor. I regale her with my failures as well as my triumphs. As she proof reads many of my stories or listens to some of my speeches, she will often tear up. She remembers how difficult it has been over the years. She also knows it takes all of my efforts to keep things safe. Having that kind of support at home provides balance and is invaluable.