We pilots tend to overestimate our abilities whether we know it or not, that is part of the pilot psyche, I think. From the newly minted CFI who thinks strapping into a jet fighter is no big deal to the young airline first officer who sees no difference between what he or she is doing for a living than the "old man" in the left seat. But for all of us, at some point we have to admit that the next step is "too much airplane."

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-10-31

This is intuitively obvious at the bottom end of aviation. There was a study placing a number of U.S. private pilots in an airline simulator and none were able to successfully land the airplane. For a humorous discussion of this: "How do you land an aeroplane?" Quite Interesting.

This isn't so obvious once you've achieved some experience and confidence, perhaps over confidence. Let's say you are a highly experienced Learjet pilot sitting in the back of a Gulfstream and both pilots pass out. Could you get the airplane on the ground safely? Probably. Now let's say you are a passenger on a Boeing 737? Maybe. Boeing 747? You might be surprised. But let's say you are a very good Learjet pilot and now let's say the airplane in question is the Concord. Or the space shuttle. At some point you have to understand the next airplane is too much airplane. We each have our limitations. For me, I think anything with a tail wheel might be too much airplane.

1 — Case study: Pilatus PC-12 N950KA

1

Case study: Pilatus PC-12 N950KA

PC-12 N950KA accident wreckage, right quartering view, NSTB

In early 2012 a businessman/pilot decided he would like to upgrade from his light airplane single into something much faster and capable of supporting his business and personal needs and put out the feelers for an airplane along those lines. A friend of mine got the call to bring a Pilatus PC-12 from the east for viewing in the Midwest. A salesman joined them and tried to convince the businessman the PC-12 was just the airplane for him. My friend took them both up, with the businessman in the left seat. It became quickly apparent that the businessman was in over his head but was determined to enter the world of turbines. My friend strongly emphasized that the PC-12 is a lot of airplane and that the businessman should consider only flying with a much more experienced instructor in the other seat until he had gained considerably more time in the airplane. His advice went unheeded. The businessman eventually got his PC-12, not the demo airplane, and managed to log 14 hours after minimal training. The result was, in a word, predictable. For more about this accident, see: Case Study: Pilatus PC-12 N950KA

The airplane was mechanically sound flying in conditions well within its capabilities. The pilot did not have a lot of instrument experience and when the autopilot disconnected in instrument conditions, the pilot's first reaction was to press the autopilot's test button as the bank angle increased from 25° to 50 in 10 seconds and to 100° about 20 seconds later. The airplane accelerated to 338 knots, well above its limiting speed, and appeared to break up in flight. All six persons on board were killed.

In the words of the accident report, "the pilot likely met the minimum qualification standards to act as pilot-in-command by federal aviation regulations." But the airplane, the high altitude, and the instrument conditions were too much for him.

2

Case study: Lear 35 N452DA

There are circling approaches and then there are circling approaches. This is the case of the latter. If you began your instrument flying career in a small piston-driven aircraft, chances are you were taught to glue the airplane to the circling MDA while keeping strictly within those Category A obstacle clearance radii. Even if your first taste of instruments was in a jet, the same rules held true but probably with higher MDA and larger radii. Either way, that is the way you train circling approaches. That is not the way you fly them. So we as an industry do a terrible job of teaching pilots about the dangers of the circling approach and how to mitigate those dangers. With a little experience you learn that. But what if you don't have that experience?

The crew of N452DA did not have that baseline of experience, were weak instrument pilots, and had track records of training difficulties when it comes to circling approaches. They found themselves having to circle under visual conditions at Teterboro in a very windy day. I think the pilots were under the impression they had to do this at the circling MDA and within the radii. Both of those ideas are wrong. Their attempt failed and they were both killed. For more about this accident: Case Study: Learjet 36 N452DA

It is far too easy to say they were not up to the task of flying their high performance airplane into a demanding airport under extremely demanding conditions. (I was scheduled to fly there just a few minutes before them but opted to divert instead. Was the approach doable in that airplane under those conditions? Yes. But the Lear 35 was too much airplane for them that day.

3

Case study: Lion Air 610

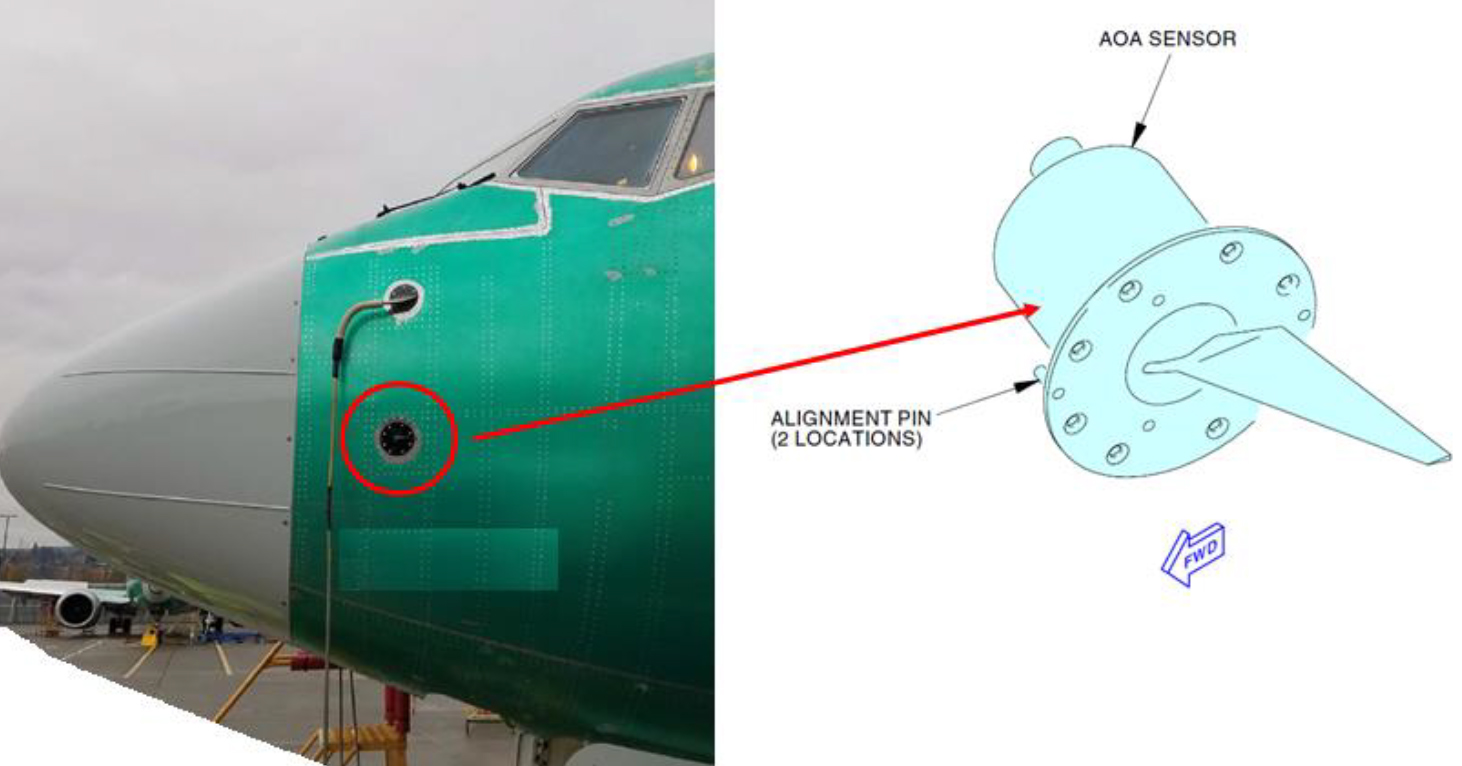

Angle of Attack (AOA) sensor,

KNKT.18.10.35.04, figure 7

Much has been made about the Boeing 737-MAX's design and many are quick to blame that design for the death of the 189 people aboard Lion Air 610 as well as the 157 on board Ethiopian Airlines 302 on March 10, 2019. The installation of larger engines meant the airplane would be unstable in some, rare flight regimes. To counter this without having to apply for a new aircraft type certification or require additional pilot training, Boeing relied on an electronic gizmo called "MCAS" and assumed pilots would treat malfunctions as they would any other pitch trim abnormal. But on these two crashes, that was a bad assumption.

So the blame game can be stated thusly: the aircraft manufacturer took a short cut in the design when installing what they considered an automatic and transparent system. Two airline crews were caught and now people are dead. But is that really what happened?

The pilots of Lion Air 610 made a lot of mistakes and could have survived had they simply pulled the throttles back, kept the airplane configured, and returned to land. They could have also survived had they simply placed the pitch trim switches to "cut out" and finished the flight manually trimming their stabilizer. But it is hard to blame pilots who are plucked off the street with very little experience, given minimal training, and are allowed to continue flying even after years of failing checkrides and demonstrating to any objective observer that the Boeing 737 MAX was more airplane than they could handle.

For more about this accident: Lion Air 610.

4

The circle of life

We pilots tend to have egos that teem with self confidence. But, to be fair, that is a requirement to do what we do: defy gravity. But experienced pilots tend to temper their egos because they've seen their own limitations on the field of battle.

I had the good fortune of flying a Gulfstream V for a charter operator that paired me with a very long list of contract pilots with varied background. I shared the cockpit with highly decorated fighter pilots as well as airline captains with decades of experience in the left seat at name-brand airlines. As good as they were in their previous lives, they were novices in the Gulfstream.

I've also had the good fortune to fly various jets as a "guest" pilot on behalf of the magazine I write for. I have become accustomed to becoming a professional novice. Think of it this way. Put an exceptionally talented crop duster pilot who has never flown a jet in the left seat of a large Boeing or Airbus, and you might not end with a successful landing. But put an accomplished Boeing or Airbus pilot with no crop duster experience, and your crops won't be getting treated the way they should and the pilot might not survive either.

In other words: a lack of experience or training can make any airplane too much to handle. The operator should never put a pilot in such a position. But the pilot should never accept that position either.

References

(Source material)

Please note: Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation has no affiliation or connection whatsoever with this website, and Gulfstream does not review, endorse, or approve any of the content included on the site. As a result, Gulfstream is not responsible or liable for your use of any materials or information obtained from this site.