Okay this is a long story with the correct lessons but they were applied for the wrong reason. But they paved the way for the real emergency to come . . .

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-25

The Adventures of Lieutenant Tutti Fruitti

“There are three secrets to receiver air refueling,” Captain Nick Davenport announced to me after our first training sortie, “you master these you will never have problems behind the tanker.”

“What are these secrets,” I asked.

“What the hell are you talking about, Albright?”

And so it went. "The Nick," as everyone called him, was really a pretty good instructor, but receiver air refueling a large airplane was certainly an eye opener. I got the power thing down pretty quickly: slow and deliberate nudges of the four throttles coupled with pitch changes followed by a lot of patience. You don’t effect the inertia of 200,000 pounds of airplane at 25,000 feet instantly. But the lateral, that was a handful.

I chased the tanker around the first turn and immediately fell behind as I slid outside. Nick took the airplane and got us close again. ‘You got it.”

As I started to settle down I realized matching the tanker’s wings to my own made things easier in the turn. “The tanker’s wings become my horizon,” I said to myself over the interphone.

“So, grasshopper, you have learned the first secret on day one.” Nick gave me a thumbs up from the left seat. “A quick study,” he said turning in his seat to face the navigator, “we must keep an eye on this Asian.” Our Hawaii unit was filled with Asians, but I was the first in a pilot seat and Nick seemed to enjoy pointing this out to me, over and over again. “Good job, copilot-san.”

The navigator didn’t agree, I don’t think. He got nauseous from my over controlling and lost most of his lunch before the second turn. Despite all that, I got to the point after five sorties where I could hang on to the boom the minimum time and was sent to my check ride. The check ride went well, but my over controlling those ailerons forced the evaluator to make a comment during our debrief.

“Lieutenant Albright,” he said in his super-serious flight examiner voice, “you are well ahead of your copilot peers but you need to settle down behind the tanker. Less is more, remember that.”

“Yes sir,” I said. Of course I knew that. It was true in general when flying airplanes, smaller control inputs made in a timely fashion are better than large inputs made too late or too erratically. I could do that in all phases of flight, but it wasn’t working for me behind the tanker.

For the next few months we mixed training sorties with operational missions, both usually involved taking on gas from a transient tanker from the mainland. On the operational missions I was relegated to watching, they certainly didn’t want me making our high ranking passengers sick. I resolved to get better.

On a magical day in August, Nick was holding our airplane rock steady behind a tanker, almost perfectly. He was about five degrees right of center, but the limit was ten and he was planted with no lateral movement. It was beautiful.

“If you can plant this thing five right,” I asked, “why not plant it dead center?”

“Good question, grass hopper.” Of course he wasn’t volunteering the answer. After a minute he starting throwing hints. “Put your hands on the yoke and tell me if something, anything, appears odd to that brain underneath your yellow skin.”

I did as requested. My first thought was there was little movement, perhaps a tremble. It was definitely top notch “Less is More” in action.

“No,” he said, “that ain’t it.”

I looked down at the yoke for clues my hands would not give me. “The yoke,” I said in astonishment, “is a good deal right, asking for a right bank.”

“Are we banked to the right, grasshopper?”

“No.”

“What causes lift?”

“A differential in pressure,” I said from years of aeronautical engineering, “between the top and bottom of the wing.”

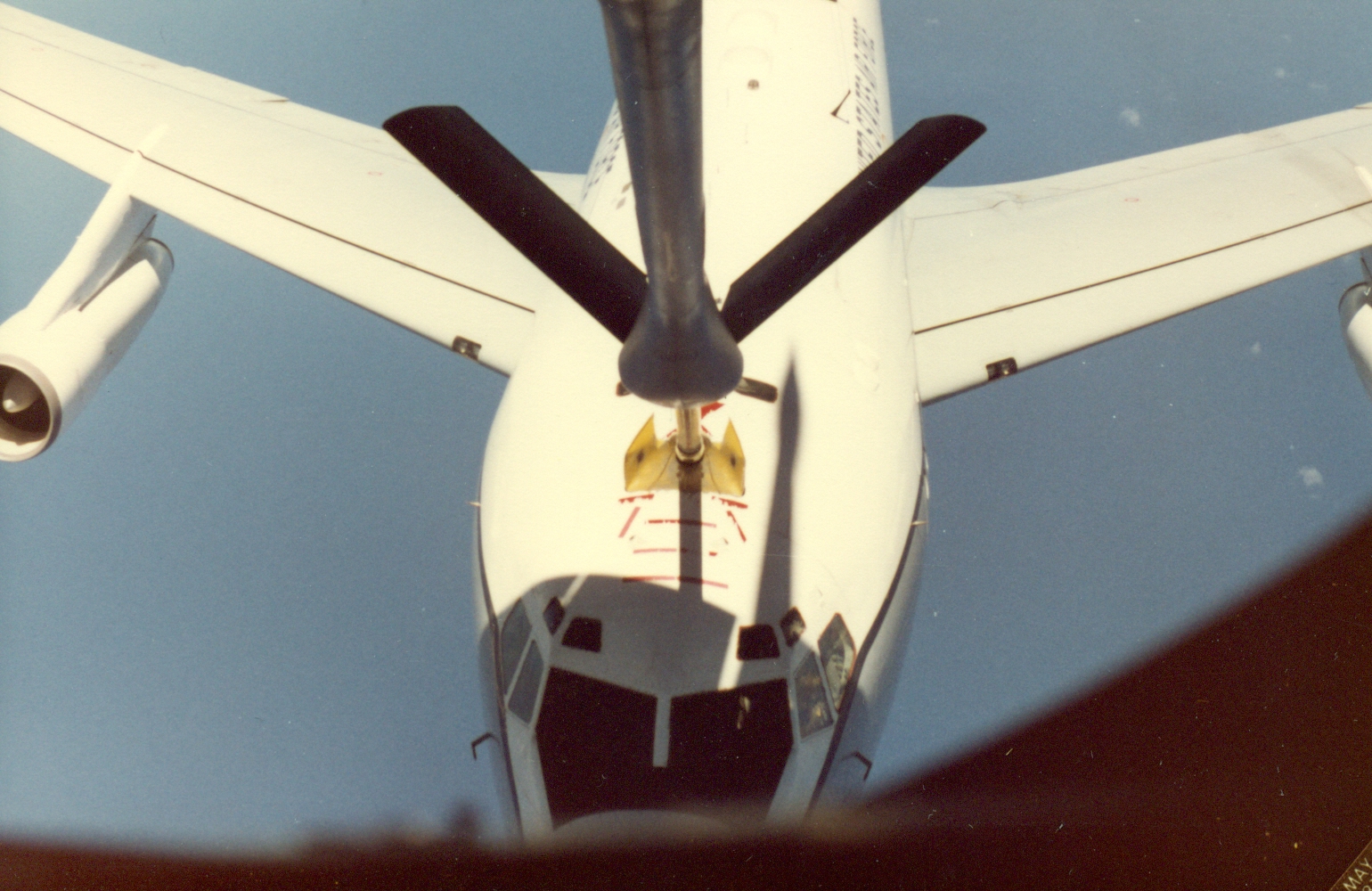

“And what happens to the pressure on the top of the wing when flying just below and behind the tanker?”

“It increases of course,” I said, “which robs the receiver of lift and requires more power.”

“What if a receiver,” he asked, “oh, like us, is offset to one side or another? Wouldn’t that make the change in lift different on each wing?”

“It would make the wing on the outside,” I said, thinking aloud, “our right wing right now, produce more lift and that would induce a roll to the inside. So to counter that…”

I looked again at the yoke. It was now obvious.

“You now have unlocked secret number two, grasshopper.” Nick moved the airplane to the left, now five degrees left. The yoke was tilted heavily to the left and yet we were wings level to the tanker and to the earth. “Now watch me move back to the right, but notice what I do with the ailerons.”

Nick relaxed the yoke’s tilt to the left but then put most of it right back in. He repeated that, over and over, but the return position of the yoke was getting progressively smaller until it was zero. And dead center is where we sat.

“Moving right,” I said, “you move the ailerons right but you keep them biased to the left. The neutral position to the left is to the left.”

“Mango five one,” Nick said over the radio, “request disconnect.” The tanker fired the disconnect circuit and the boom nozzle released itself from our receptacle and we crept backwards fifty feet. “So you’ve got secret number three then. Now you try it,” he said.

And so I did. It was a joy. I was rock steady in the center of the envelope. “Sneak to the right a little.” I did. “Now back to center, slowly.” I did that too.

“Teach more,” Nick said to the rest of the crew over the interphone, “I cannot. Knows what he needs to know, this Asian does.”

A week later we were on an operational mission with an airplane full of passengers and the full complement of radio operators, crew chiefs, security guards, and a stewardess. (We still called them stewards and stewardesses back then.) The trip started south of Oahu behind a tanker to take on a full load of fuel before heading west.

“James, you take this one,” Nick said as the navigator checked in with the tanker, “just remember the tanker is going to be struggling with the power as his airplane gets lighter with all the fuel he’s giving us. You will need to anticipate needing more power and him not doing such a good job with his throttles.”

I nodded and took the airplane. It was my first receiver air refueling with passengers on board and I had to get it right. And I did. The engineer counted off our fuel on-load: “Ten grand.” “Twenty grand.” He kept going. Once we got to one hundred, we could disconnect. But before that I had a few turns to negotiate. The first was to the east, putting the sun off our left front. The turn was easy – the tanker’s wings are my horizon – and the count continued “Forty grand.”

For the next five minutes the wings would be level and I just had to keep my increasing throttle position from upsetting my pitch controls. At one point I started to wonder about the smell of bacon. Bacon? Oh yes, Mandy was cooking lunch and BLT’s were on the menu. The galley was just behind us.

“Seventy grand,” the engineer reported.

“A minute from turn,” the navigator added.

The tanker banked gently to the left and I followed, sliding a bit to the right but correcting. This was fun. The tanker blocked the sun for a few seconds but soon it would be right in my face. I squinted, in anticipation. A few degrees later there was the bright flash I was expecting, and a loud bang from inside the cabin I was not.

Then there was a sweet, acrid smell. Then. . .

“Fire!”

“Breakaway, breakaway, breakaway!”

I pulled all four throttles to idle while holding the yoke firmly to prevent the nose from diving and causing us to accelerate below the tanker. Our chief goal here was longitudinal separation.

“Whadoya got?” Nick asked turning in his seat to the engineer.

“Don’t know,” the engineer answered, “I heard a bang, somebody yell fire, and I can still smell it. Smells electrical.”

“Go back and look,” he ordered the engineer. “Nav, we got enough gas to make it to the Philippines?”

“Twenty short,” the navigator said.

“Tell the tanker to stick around,” Nick commanded, “we might make this work.”

“Nick,” I said, “we got to get this on the ground, as soon as possible. If we have an electrical fire, we need to land now.”

“Really?”

“Nick,” I said while turning north, away from the tanker and towards Oahu, “if you have a fire on an airplane and you don’t land in fourteen minutes or less, you aren’t going to.”

Nick sat and pondered.

“Captain,” the engineer reported back, “Everyone heard the noise, and say they saw a bright flash from the communications rack. We don’t see any evidence of fire but you can really smell it. It might be something inside one of those racks.”

“Whadoya think?” Nick asked.

“They don’t pay me to think, Captain.”

Nick turned to me.

“Let’s declare an emergency and land this thing while we can.”

“Oh what the hell,” Nick shrugged, “okay, let’s do that.”

We got the airplane on the ground in ten minutes and taxied back to our squadron with no evidence of fire. The airplane was impounded for two days with still no, dare I say, smoking gun. Nick summoned the crew.

“We have to figure out what happened,” he said, “the maintainers are coming up with goose eggs.”

There were ten of us: two pilots, an engineer, a navigator, a flight attendant, and five communications officers. The front of the airplane is organized in that order, the two pilots seats, followed by the engineer seat, the navigator’s desk, the galley, and the comm compartment. After that is the passenger section, but the smell and bright flash were just forward of the comm compartment.

Each communications specialist – two radio operators, a satellite operator, and two teletype operators – agreed there was a bright flash followed by a loud bang forward of their compartment, towards the cockpit. The navigator and engineer heard the bang behind them. Everyone remembered the sweet electrical smell.

“Like burning insulation,” one of the radio operators said.

“Yeah,” I agreed, “I know that smell. It was electrical.”

“But there isn’t any evidence of an electrical fire,” Captain Nickel said, “and until we figure this out we aren’t going anywhere.”

“Why’d we turn back any way,” one of the radio operators said, “I’d much rather be in the Philippines right now.”

Nick said nothing.

“The copilot,” said the navigator, “heard fire and freaked out.”

I glared at the navigator as the communications crew snickered. They weren’t allowed to laugh at an officer, to his face, but snickering at a lieutenant copilot was certainly within limits.

“It was my decision,” Nick said while raising his hand, “we can’t take chances with fire. Everyone okay with that?”

Slowly, but surely, there were nods around the table.

“Mandy,” the engineer said finally, “you’ve been quiet. Everyone gave their story but you.”

“Well,” she said with a noticeable blush, “I was hoping it wasn’t me. But it was.”

For the first time everyone was silent. She took a breath and revealed all. “I was finished with the bacon, I had all the tomatoes sliced and was waiting for the bread to toast. I poured some Tutti Frutti mix into a carafe with one hand and reached for a jug of water with the other when a bright flash of light from the cockpit startled me. I dropped the Tutti Frutti and the powder flew everywhere.”

“The air conditioning system vents into the comm compartment and goes forward and aft. That’s why we smelled it the most strongly,” I offered, “and I guess this carafe was made of metal?”

“Yes.”

“Hence the loud bang,” Nick said, “that explains everything but the fire.”

“I guess that was me,” said one of the teletype operators. “I saw the flash, heard the bang and then the smell. I guess I just assumed it was a fire.”

The rest of the comm team pointed fingers and started hooting.

“No,” Captain Davenport said, “we aren’t here to blame anyone. It is good that we found out what really happened and learn from it. I guess Mandy in the future just tell us when something like that happens. No problem at all, we want to always err on the side of keeping safe.”

Among our crew all was forgiven but I was saddled with the name “Lieutenant Tutti Frutti” for another three months when we had a real cabin fire. (For that story, see Flight Lessons 2: Advanced Flight, Chapter 4.)