I don’t often succumb to the popular trend to turn a noun into a verb, but in this case it seems appropriate. Being a chief pilot is a process that is unique, not simply leadership and certainly more than the accounting, scheduling, and other procedural tasks encompassed by the title. For those of you in the commercial world, I know that “chief pilot” has a specific regulatory role under 14 CFRs 121 and 135. But for our purposes here, the chief pilot is the pilot in charge of a flight operation. If your title is the director of aviation, the flight department manager, or anything else that involves keeping all the pilots of an organization pointed in the right direction, that makes you a chief pilot in my book.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-06-15

The uniqueness of the role cannot be simply explained because each organization tailors the uniqueness further still. As with many things in life, a way to understand how to do something correctly is to observe it being done incorrectly. Perhaps a few examples will help.

Example 1 — Leadership where it is desperately needed (low experience levels)

Example 2 — Leadership where it is desperately needed (high experience levels)

Example 3 — Leadership where minimal leadership is needed (high experience levels)

Example 4 — Leadership where minimal leadership needed (high experience levels)

5 — Why do you need leaders in a flying organization?

7 — Principles: consider, adopt

Example 1

Leadership where it is desperately needed

(Low experience levels)

My first squadron in the Air Force after initial pilot training was Loring Air Force Base, Limestone Maine, just three miles from the Canadian border. This was during the height of the Cold War when the Russians had a nuclear submarine parked just off the coast. The Air Force realized none of our aircraft were going to survive the first 15 minutes of World War III and wanted to close the base. The Maine congressional delegation didn’t want to lose the base and prevented that from happening. Our morale, to say the least, was low. So, we had squadrons of crewmembers who knew they would have no impact on the mission, had little chance for promotion, and were living in an isolated part of the country where summer consisted of two weeks in August.

The only concern I ever witnessed from the two squadron commanders I worked for at Loring was the priority of keeping the alert sorties manned. (We didn’t have any women crewmembers back then.) Pilot instrument skills were poor, enlisted discipline was poor, and officer professionalism was in short supply. The good pilots kept to themselves because the pilots in leadership positions were usually bad pilots. The same can be said for their professionalism.

Because of the weather and our position as the last base before heading to Europe, the flying was actually pretty challenging for a brand-new copilot. Most of the copilots seemed to eventually have that spirit beaten out of them. I didn’t really mind the assignment that much, but that was a rare sentiment. The Air Force mandated a minimum three-year tour, and everyone schemed on ways to make it exactly three years, and not a day longer. But a copilot usually had to stay a few years longer if he hoped to upgrade to the left seat. I never upgraded but I made it out in 22 months. (I write a bit about this squadron in Flight Lessons 1: Basic Flight.)

Example 2

Leadership where it is desperately needed

(High experience levels)

My next squadron was flying Boeing 707s (EC-135Js) in what started out to be a high priority mission with great flying and high morale but, five years later, was little better than my tanker squadron in Maine. But this new squadron was in Hawaii, so it was still an attractive assignment and people volunteered for it. Once assigned, few wanted to leave.

We didn’t accept new pilots or navigators right out of training and there was an interview process. Unlike the tanker squadron, this squadron had a say in who they hired. That meant we had high caliber people for as long as we had high caliber leadership. In my five years there I served under three commanders. The second of those was top notch and valued crewmembers who could do their jobs and officers who acted as such. Under his leadership, morale was high and passenger complaints were low. He was eventually plucked from us for bigger and better things. He was replaced by a political hack who got the assignment for his performance as a staff officer. (I write at length about Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Spindler in Flight Lessons 2: Advanced Flight.)

Spindler was a poor pilot and because he couldn’t recognize good pilot skills when he saw them, he did not value true pilot skills. The same can be said of his skills as an officer. Because he had no credibility in either area, he commanded zero respect in both. Poor pilots with good political skills were elevated to higher positions and he recruited cronies from outside to populate other leadership roles. Morale plummeted and people started lining up at the doors to leave this once sought-after assignment. People were volunteering to leave paradise. Spindler tried for two years to get rid of me. He finally did.

Example 3

Leadership where minimal leadership is needed

(High experience levels)

While in Hawaii I managed to upgrade several times from copilot to aircraft commander to instructor pilot to examiner pilot. Since I grew up in Hawaii and we didn’t have children at home yet, I was able to focus on the job and held positions as the wing’s chief of flight safety and chief of flight standardization. The squadron was filled with future airline pilots who refused any training that would lengthen their commitment to the Air Force, so I ended up getting training as an accident investigator and an instrument instructor. In short, I ended up as a sought-after pilot and was hired by what turned out to be the best assignment for a pilot flying large airplanes in the Air Force: the Boeing 747.

I did not have any leadership roles in that squadron. I started as a copilot and ended as an instructor pilot with the formal title as the squadron’s functional check pilot, the guy who flew the airplane after modification or heavy maintenance. I was never in charge of people, other than as a crew commander. But in the five years I was there, I witnessed the leadership style of five different commanders. The one constant in the squadron was the chief scheduler who had been in the squadron for more than ten years. He was a navigator with no desire (or chance) to command and was happy where he was. I write about Lieutenant Colonel Alton Gee in Flight Lessons 2: Advanced Flight and Flight Lessons 4: Leadership and Command. When a new squadron commander attempted to do anything he deemed silly and counterproductive, Alton would say, “how do you lead men and women who don’t need to be led?”

I thought about that a lot. The squadron was what the Air Force called a “special duty assignment” back then. You had to have a flawless record and survive a rigorous interview process. Everyone who showed up was sure to do well at promotion and the pilots would walk away with a coveted Boeing 747 type rating. And, as importantly, everyone understood the importance of the mission. In other words, nobody needed extra motivation to do the job.

Of the five squadron commanders, only one rose to Alton’s high standards. That commander, let’s call him Lenny, was fired for allowing two of our Boeing 747s fly fingertip formation. Alton summed up his command perfectly. “In twelve months in command the only thing Lenny did of consequence was move the coffee bar from one room to another. Yup, old Lenny was a pretty good commander.”

That may seem wrong and I would say Lenny’s flight antics did justify his dismissal. But Alton’s summation was accurate when compared to the other commanders. We were in a high visibility outfit and got a lot of flak from the real Air Force and a lot of meddling from the Pentagon and White House. Every level of crewmember knew how to do their jobs and left alone, did a fine job of it. Because it was a high visibility squadron and the political stakes were immense, most of our commanders did a poor job of protecting us from above and some even added to our problems. The worst were those who did little more than to pass on the edicts from higher echelons, afraid to push back lest their careers be jeopardized. Lenny did his best to insulate us, the troops, so we could do our jobs. Lenny was a pretty good commander after all.

Example 4

Leadership where minimal leadership needed

(High experience levels)

My next assignment was out of the cockpit, but I followed that with Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland as a new pilot in a Gulfstream III (C-20) flying for the 89th Airlift Wing. Our squadrons were very large, and every crewmember was hand-picked to pass what I called “The Beauty Contest.” You had to have an impeccable record, but you also had to look the part. Top leaders were “movers” on their way to bigger and better things. But the intermediate level leaders were those who grew up flying the line and hoped to stay in the squadron forever. At first glance this would seem ideal. Having an experienced cadre ensured continuity. But this same cadre grew complacent and corrupted the culture of the wing. The squadrons knowingly violated Air Force and governmental regulations, reasoning that “we are better than those the rules were written for.”

The system had become so corrupt that even the base weather shop stopped giving forecasts below minimums, knowing that we pilots were going to attempt the landings regardless. The maintenance wing looked the other way as Boeing 707 crews routinely violated maximum landing weights. While I was there, I worked for three squadron commanders and two group commanders who managed to look the other way often and whenever needed. We pilots in the trenches had little choice but to try to survive within the letter of the law when we could, but play the game when we had to. I ended my assignment there as the wing’s chief of safety and managed to put an end to the overweight landing practice. Of course, I made a lot of enemies and they chased me out of the wing. I ended up at the Pentagon where I started the process of grounding those Boeing 707s. I write about this in: Flight Lessons 3: Experience.

5

Why do you need leaders in a flying organization?

From these experiences, we see there are at least four cases for strong leaders in flying organizations.

- You quite often have young crewmembers who need to be shown the way to avoid starting off on the wrong foot. Flying airplanes can be done with very little preparation and care; but flying airplanes safely requires a great deal of training and discipline.

- Even with high experience levels and good motivation, a rotten leader can corrupt those below and turn that motivation sour.

- Another function of leadership is to protect the operation from external factors. Given high quality people who know the job and are motivated to do it, leadership may have very little to do other than provide the tools for the “troops” to do the job. But each level of leadership has levels above it, and those levels may not have the same understanding of the job at hand.

- High quality “troops in the trenches” and a well-intentioned leader on top is, of course, what you want. But quite often in these situations you have a middle tier of people to contend with and it is these people that can really make an operation shine or flounder.

Of course, there are many other models to consider, but these four should give you an idea of just how diverse the need for good leadership is. Now these examples were from the Air Force, where I gained my first 20 years of flight experience. Here we are, 20 years after that, and I’ve seen all four models as a civilian too. I think examples three and four are the most common templates in corporate aviation. Everyone tends to be motivated to do the job, but we can be let down by leaders who have never been trained as leaders and are out of their depths when dealing with people. Organizations tend to pick their chief pilots from the best pilots or the pilots who have managed to stick around the longest. A best pilot isn’t always the best leader. The pilot with the most time may just be the one with no employment prospects elsewhere.

If all of this sounds gloomy, it is. As a check airman for a large management company years ago, one of my jobs was to visit small flight departments to conduct line observations and audits. The pilots tended to be very good; the chief pilots were hit and miss:

- Good pilot, good leader. These leaders: had a lot of experience in the trenches where they could observe leadership from afar, or some kind of formal leadership training and experience, or had some kind of natural aptitude for it.

- Good pilot, poor leader. These leaders knew how to fly airplanes and commanded the respect of their people because of it. But they had no idea about how to motivate people, how to deal with personality issues, or how to deal with management.

- Poor pilot, good leader. These leaders tended to do well with management and not too badly with their people. But without the respect of the crews, these leaders were rarely supported from below when dealing with difficult situations. The mission tends to suffer and because of that, these leaders rarely last long.

- Poor pilot, poor leader. This, regrettably, is a common model. The poor pilot may hang around the longest because he or she is an unattractive hire outside the organization. Because he or she sticks around the longest, he or she may eventually be the only choice for the chief pilot role. Alternatively, the candidate looks good from management’s perspective because the rest of the organization does well. But once in command, these types of leaders usually have difficulty recognizing talent or may even come to resent it. The saying that “A’s pick A’s, B’s pick C’s” applies here. A poor pilot/leader tends to attract other poor pilot/leaders.

6

You, the chief pilot

So now you have been elevated to the chief pilot position. If you are a typical corporate aviation pilot, this could be the pinnacle of your career. It may be what you’ve hoped for, or it could be a surprise. No matter how you got here, you obviously want to do well. But few of us are trained for this moment. Our only education was that which we received watching other chief pilots. We learn from below; I used to be fond of saying, “I’ve learned from the worst.”

The world is filled with leadership courses and most of these, regrettably, do little to prepare you for the job. Because every leadership situation is unique, you can hardly be prepared for every situation with a week-long, month-long, or even year-long course. This is one of those times were a lot of experience is invaluable. But how do you get that experience? More importantly, how do you avoid becoming a bad example during your first time at bat?

Allow me to propose a course of action. I have been a chief pilot three times and I’ve made a lot of mistakes along the way. Truth be known, I’ve turned down more chief pilot jobs than I’ve held. You might wonder that after such a mistake-ridden past how is it that I keep getting invited for another turn at bat? I can’t answer that, but I can answer what I think is a path to bypassing my bad experiences so you can jump right into a good one. I think you first need to have a core set of principles. You need to gain experience before you actually become a chief pilot and you can do that by being a meticulous observer. And, finally, once given the position you need to accelerate your learning so you can improve every day on the job to the point everyone thinks you are a natural born leader, even when only you know that you are not.

7

Principles: consider, adopt

Integrity. Most of us are innately honest: we value the truth in others and in ourselves. But the temptation to take shortcuts in aviation is hard to resist and the push to do things faster, cheaper, and with less effort comes from all directions. My first chief pilot job was cut short because I refused to bend on the rules, so my integrity would seemed to have done me little good. But my reputation grew, and other jobs followed. Was it a mistake to be a stickler for the rules? No, but I was so dogmatic about it I think it may have threatened those I worked for. I realize now that there was a way to maintain my integrity by pushing back more tactfully. Saying "I'm not going to do that because it violates X," implies that the order giver is ignorant of the rules or wants to knowingly violate them. Saying "I think we can do this, but maybe we need a slight adjustment to live within the spirit of X," might provide just enough latitude or can prompt the order giver to come up with a solution on his or her own.

Loyalty. Through the years I noticed that most leaders had unyielding loyalty to higher levels of management. That is, after all, where their paychecks were coming from. During my first time as a chief pilot I vowed to have unbending loyalty to the troops below. But that wasn’t the right answer either. (I write about this in Flight Lessons 4: Leadership and Command.) Loyalty should go in both directions.

Courage. Even if you understand your need to keep your core principles (integrity) and need to show the necessary allegiance to those above and below you (loyalty), there will be times your decisions will alienate everyone. But if you survive (and that’s a big if!), the insulator of time will allow everyone to see your actions were for the long-term good.

8

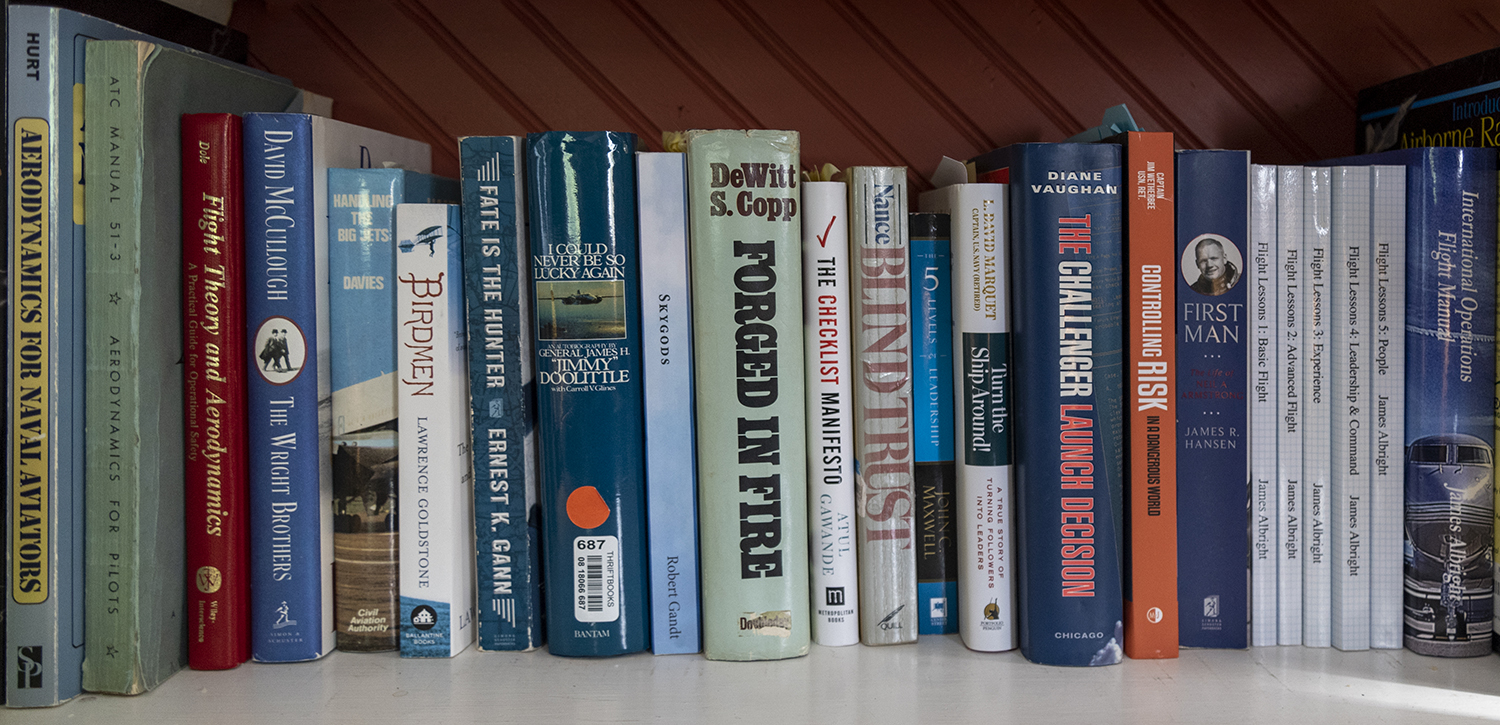

Preparation: observe, read

We all experience leadership before we become leaders, because the first step on this journey is as a follower. The best way to be prepare for your leadership roles to come is to be a careful observer of the leaders around you. You can accelerate your learning process by reading about the leaders who have failed and succeeded before you. Here is a short list to get you started.

- Albright, James, Leadership 101 – Okay, I wrote this in the sense I put pen to paper. But the person who really wrote it was a mentor of mine I call “The Nick.” I’ve been told by professors at a few colleges that it does a good job of encapsulating the leadership process. I list this first because you can finish it in about ten minutes and it will, I hope, whet your appetite for more.

- Albright, James, Flight Lessons 4: Leadership and Command, 2017 – This is a compendium of leadership styles, the good and the bad, in a military setting with a lot of civilian relevance.

- Man, John, The Leadership Secrets of Genghis Khan, 2009, Transworld Publishers – This was required reading for Army officers years ago but don’t let that talk you out of it. While the book deals with war, it does a great job of providing lessons on how to deal with subordinates and superiors.

- Coram, Robert, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, Back Bay Books, New York, NY, 2002 – This is my favorite biography of all time, about the best military officer of all time. Here you will learn more about integrity than in any other book I’ve ever read.

- Roberts, Wess, PhD, The Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun, 1985 © Wess Roberts, First Trade Edition 1990, Reissued 2009 by Grand Central Publishing – Most of us react negatively to the mention of Attila the Hun, but he has provided us with many very good ideals of leadership: improvement, stewardship, loyalty, accountability, responsibility, and decisiveness.

Yes, there are more. Here are a few: Favorite Books.

9

Execution: act, learn, repeat

This may seem out of place, but it isn’t. It is my favorite quote from my favorite book:

"Some men are born mediocre, some men achieve mediocrity, and some men have mediocrity thrust upon them. With Major Major it had been all three. Even among men lacking all distinction he inevitably stood out as a man lacking more distinction than all the rest, and people who met him were always impressed by how unimpressive he was.”

— Joseph Heller, Catch-22

I’ve worked for many mediocre leaders over the years. Some were mediocre because they were genuinely incompetent. Other were genuinely evil. But the saddest case of all was when they were obliviously mediocre. They thought they were doing everything right; they thought the troops loved them. But they were wrong. Don’t be like that.

The best way to avoid having mediocrity thrust upon you is to realize:

- You are not a natural born leader; you need to work at it.

- You will make mistakes; the key is to acknowledge those mistakes and correct them swiftly.

- The troops realize you are not perfect, pretending to be perfect will only highlight your imperfection. Acknowledge your imperfections and do the best you can.

- You will not be anyone’s favorite; none of your followers will think of you as their best friend. Some of your decisions will be unpopular but necessary. Put another way, some of your decisions will be necessary and unpopular.

- You need to be loyal to your followers, but you also need to be loyal to those you follow.

- There are things that trump your needs and desires. Among those are the prerequisites to be safe and to be honest.

There you have it. A treatise on leadership with not a lot about the mechanics of leadership but a lot on the idea of leadership. I’ve mentioned loyalty a few times and that is an important aspect of leadership. So, allow me to close with my favorite quote on the topic:

"If your boss demands loyalty, give him integrity. If he demands integrity, give him loyalty."

— John Boyd

More about John Boyd: Rule #9: Integrity vs. Loyalty.

References

(Source material)

Coram, Robert, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, Back Bay Books, New York, NY, 2002

Man, John, The Leadership Secrets of Genghis Khan, 2009, Transworld Publishers

Roberts, Wess, PhD, The Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun, 1985 © Wess Roberts, First Trade Edition 1990, Reissued 2009 by Grand Central Publishing