The ICAO cleaned up the disparate procedures for oceanic contingencies nicely about 2007, then again early 2020, and now once again November 5, 2020. So what follows below are: ICAO Doc 4444 Procedures and Reference Guides (of the procedures in two pages)

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-11-10

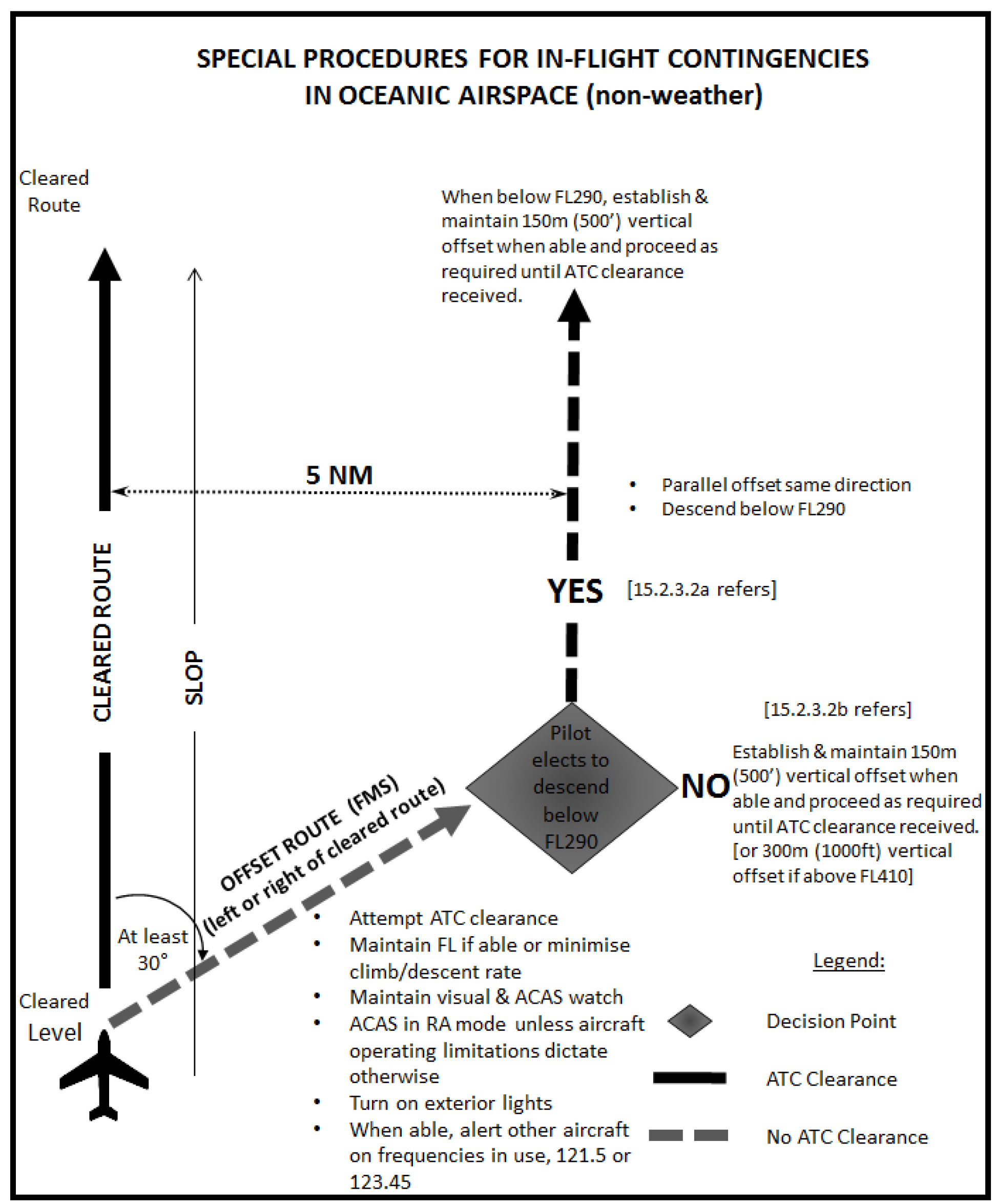

The old "Quad Four" maneuver to turn 45° away from track, offset 15 NM, pick an altitude, etc. is gone. With the exception of lost communications timing in the Pacific, almost all of the world is on a single oceanic contingency procedure. Now you diverge from the route by 30°, offset by 5 NM, and then descend below FL 290 or climb above FL 410.

Of course there may be regional differences that supersede these procedures and you should use your judgment to ensure safety. If you can communicate with ATC via voice or CPDLC, your options might expand.

1

Introduction

Although all possible contingencies cannot be covered, the procedures in 15.2.2, 15.2.3, and 15.2.4 provide the more frequent cases such as:

- the inability to comply with assigned clearance due to meteorological conditions;

- en route diversion across the prevailing traffic flow (for example, due to medical emergencies); and

- the loss of, or significant reduction in, the required navigation capability when operating in an airspace where the navigation performance accuracy is a prerequisite to the safe conduct of flight operations, or pressurization failure.

The pilot shall take action as necessary to ensure the safety of the aircraft, and the pilot's judgment shall determine the sequence of actions to be taken, having regard to the prevailing circumstances. Air traffic control shall render all possible assistance.

Source: ICAO Doc 4444, ¶15.2.1

2

ICAO procedures

Declaring an emergency is a game changer just about anywhere in the world and using "Mayday" or "Pan Pan" is the only way to change the rules of the game in some parts of the world. You shouldn't be shy about using it if you need traffic priority. I've done this eighteen times in my short life and there has never been anything negative as a result.

If an aircraft is unable to continue the flight in accordance with its ATC clearance, a revised clearance shall be obtained, whenever possible, prior to initiating any action.

Source: ICAO Doc 4444, ¶15.2.2.1

If prior clearance cannot be obtained, the following contingency procedures should be employed until a revised clearance is received. In general terms, the aircraft should be flown at an offset level and on an offset track where other aircraft are less likely to be encountered. Specifically, the pilot shall:

- leave the cleared track OR ATS route by initially turning at least 30 degrees to the right or to the left, in order to establish and maintain a parallel, same direction track or ATS route offset 5 NM (9.3 km). The direction of the turn should be based on one or more of the following factors:

- aircraft position relative to any organized track or ATS route system;

- the direction of flights and flight levels allocated on adjacent tracks;

- the direction to an alternate airport;

- any strategic lateral offset being flown; and

- terrain clearance;

- maintain a watch for conflicting traffic both visually and by reference to ACAS (if equipped) leaving ACAS in RA mode at all times, unless aircraft operating limitations dictate otherwise;

- turn on all aircraft exterior lights (commensurate with appropriate operating limitations);

- keep the SSR transponder on at all times and, when able, squawk 7700, as appropriate and, if equipped with ADS-B or ADS-C, select the appropriate emergency functionality;

- as soon as practicable, advise air traffic control of any deviation from their assigned clearance;

- use means as appropriate (i.e. voice and/or CPDLC) to communicate during a contingency or emergency;

- if voice communication is used, the radiotelephony distress signal (MAYDAY) or urgency signal (PAN PAN) preferably spoken three times, shall be used, as appropriate;

- when emergency situations are communicated via CPDLC, the controller may respond via CPDLC. However, the controller may also attempt to make voice contact with the aircraft;

- establish communications with and alert nearby aircraft by broadcasting on the frequencies in use and at suitable intervals on 121.5 MHz (or, as a backup, on the inter-pilot air-to-air frequency 123.45 MHz): aircraft identification, the nature of the distress condition, intention of the pilot, position (including the ATS route designator or the track code, as appropriate) and flight level; and

- the controller should attempt to determine the nature of the emergency and ascertain any assistance that may be required. Subsequent ATC action with respect to that aircraft shall be based on the intentions of the pilot and overall traffic situation.

Note.— Guidance on emergency procedures for controllers, radio operators, and flight crew in data link operations can be found in the Global Operational Data Link (GOLD) Manual (Doc 10037).

Source: ICAO Doc 4444, ¶15.2.2.2

Actions to be taken once offset from track

Note. — The pilot’s judgment of the situation and the need to ensure the safety of the aircraft will determine the actions outlined to be taken. Factors for the pilot to consider when deviating from the cleared track or ATS route or level without an ATC clearance include, but are not limited to:

a) operation within a parallel track system;

b) the potential for user preferred routes (UPRs) parallel to the aircraft’s track or ATS route;

c) the nature of the contingency (e.g. aircraft system malfunction); and

d) weather factors (e.g. convective weather at lower flight levels).

15.2.3.1. If possible, maintain the assigned flight level until established on the 9.3 km (5.0 NM) parallel, same direction track or ATS route offset. If unable, initially minimize the rate of descent to the extent that is operationally feasible.

15.2.3.2 Once established on a parallel, same direction track or ATS route offset by 9.3 km (5.0 NM), either:

a) descend below FL 290, and establish a 150 m (500 ft) vertical offset from those flight levels normally used, and proceed as required by the operational situation or if an ATC clearance has been obtained, in accordance with the clearance; or

Note 1. — Flight levels normally used are those contained in Annex 2 — Rules of the Air, Appendix 3.

Note 2. — Descent below FL 290 is considered particularly applicable to operations where there is a predominant traffic flow (e.g. east-west) or parallel track system where the aircraft’s diversion path will likely cross adjacent tracks or ATS routes. A descent below FL 290 can decrease the likelihood of conflict with other aircraft, ACAS RA events and delays in obtaining a revised ATC clearance.

b) establish a 150 m (500 ft) vertical offset (or 300 m (1000 ft) vertical offset if above FL 410) from those flight levels normally used, and proceed as required by the operational situation, or if an ATC clearance has been obtained, in accordance with the clearance.

Note. — Altimetry system errors (ASE) may result in less than 150 m (500 ft) vertical spacing (less than 300 m (1000 ft) above FL 410) when the above contingency procedure is applied.

Note. — Altimetry system errors (ASE) may result in less than 150 m (500 ft) vertical spacing (less than 300 m (1000 ft) above FL 410) when the above contingency procedure is applied.

Source: ICAO Doc 4444, ¶15.2.3

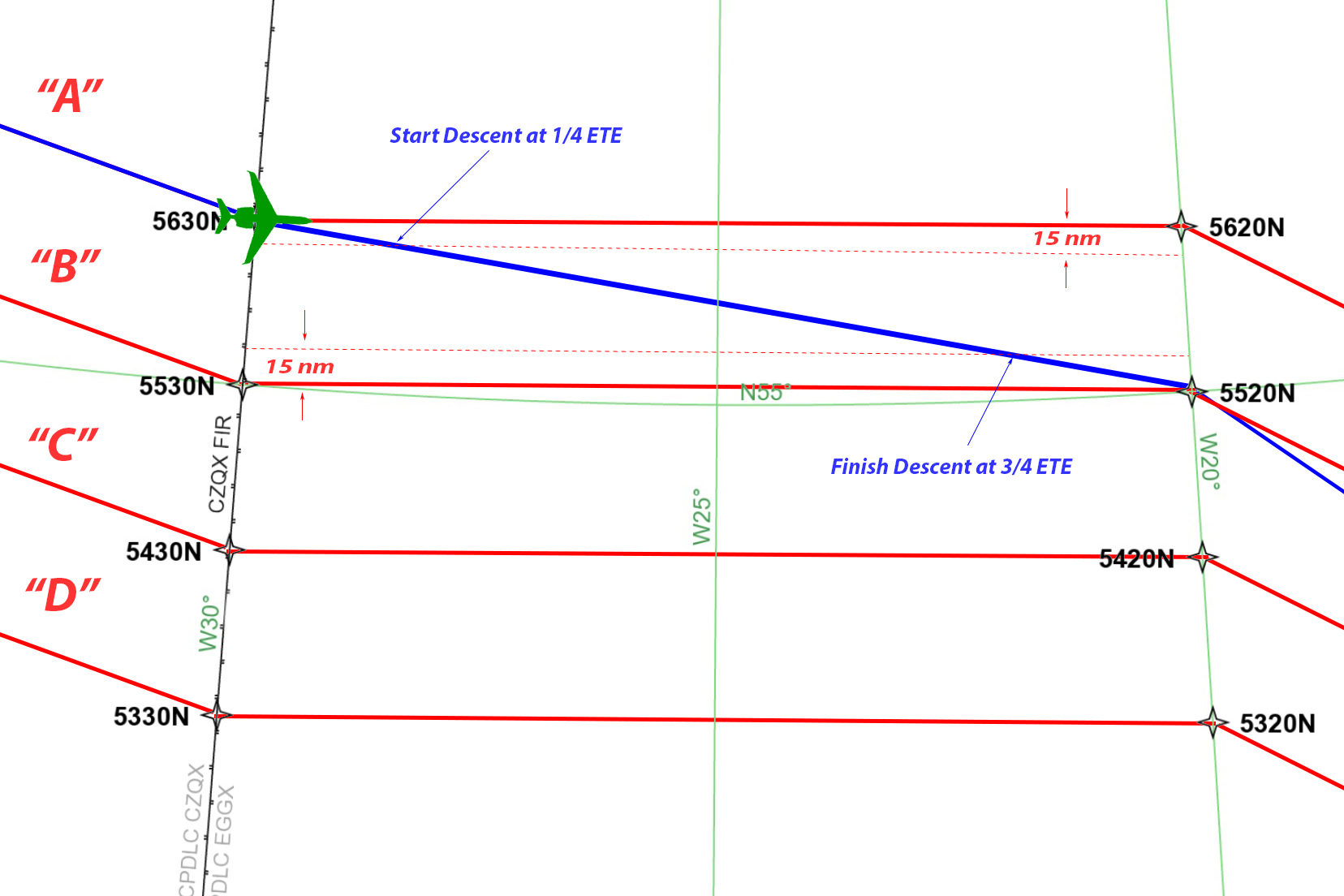

Visual aid for contingency procedures guidance, ICAO Doc 4444, figure 15-1.

3

Reference guides

Want this summarized in easy one- or two-page reference guides? The following are presented from a collaborative effort from Nat Iyengar, Guy Gribble (International Flight Resources), and Mitch Launius (30 West IP). If you are flying a G450, G550, or G650 there are specific guides. Otherwise there are general guides. You can use the PDF versions as is or customize the DOC versions. The authors emphasize that they are open-source documents from a collaborative effort over many years.

General Aircraft Doc 4444 Contingencies (PDF format)

General Aircraft Doc 4444 Contingencies (DOC format)

Loss of ATC Services While Oceanic (PDF format)

Loss of ATC Services While Oceanic (DOC format)

Oceanic Waypoint Briefing (PDF format)

Oceanic Waypoint Briefing (DOC format)

The Gulfstream versions mention that you can approximate L/DMAX by flying VREF (on the display controller or TSC POF pages) + 10 knots. They got this from pilots at Gulfstream and it seems about right. There is a debate among Gulfstream company pilots about "Normalized AOA" and using it as a flight instrument. Depending on who you talk to, a normalized AOA takes into account all sorts of factors or is nothing more than the stall angle of attack in degrees converted to 1.0 with lower values attributed to lower angles. I have taken AFM data to come up with L/DMAX = 0.30 AOA. More about that here: L/D-max. I certainly wouldn't fly slower than VREF + 10 at altitude. Thanks again to Nat and his team for these. Jon Cain adapted these for the GVII.

G450 Doc 4444 Contingencies (PDF format)

G450 Doc 4444 Contingencies (DOC format)

G550 Doc 4444 Contingencies (PDF format)

G550 Doc 4444 Contingencies (DOC format)

G650 Doc 4444 Contingencies (PDF format)

4

Letter

Dear James,

Your latest oceanic contingencies article got me to thinking more about the process. Essentially one is supposed to turn off the track and slow to drift down speed and continue in the same direction until descending below FL 290 before making the turn back to your alternate.

I dug into the flight manual performance section regarding single engine procedures. Average numbers for our plane at weights and altitude near the single engine ETP point: 220 IAS, 380 TAS and a 300 fpm descent rate. Assuming no wind and starting from FL 350, it would take about 22 minutes and 140 NM to get below 290. Then another 22 minutes not including the turn to get abeam the point at which the engine failed in the first place. Roughly 45 minutes spent before making headway to your landing. This seems counter intuitive and I was hoping for your insight.

Signed, R. Fader

Fort Lee, New Jersey

Dear Mister Fader,

It is counterintuitive in many more ways than just the safety of your airplane. In the North Atlantic, especially, you have the safety of everyone around you to worry about. In the days before the skies became so crowded, the answer was to indeed drift down according to your aircraft’s best ability so as to milk every last forward mile possible. But these days, doing that could endanger other airplanes. Is it morally right to endanger an airliner filled with hundreds of people to improve the odds for the ten or so sitting behind your cockpit? But we do have greater communications and surveillance as well as TCAS to help out.

So, all that being said, here is my plan. I try to allow for enough fuel to keep a proper offset until above or below the tracks. If it happens, I’ll be communicating with the air traffic service unit and trying to get the best drift down I can, but I won’t do that unless I have clearance. This means you cannot be content with having just enough ETP fuel to make your destination. Here is some food for thought: The Great Escape.

References

(Source material)

ICAO Doc 4444 - Air Traffic Management, 16th Edition, Procedures for Air Navigation Services, International Civil Aviation Organization, October 2016

ICAO Doc 4444 - Air Traffic Management, 16th Edition, Amendment 9, Procedures for Air Navigation Services, International Civil Aviation Organization, November 5, 2020

NAT OPS Bulletin 2018-05, Special Procedures for In-flight Contingencies in Oceanic Airspace, 17 Dec 2018