Psychologists will tell you that the concept of authority gradients plays a vital role in high-stakes environments, like in aviation, healthcare, the military, and law enforcements. The authority gradient refers to the perceived or actual difference in power, status, or authority between individuals in a hierarchy. This gradient influences how the team members communicate and how decisions are made.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-09-01

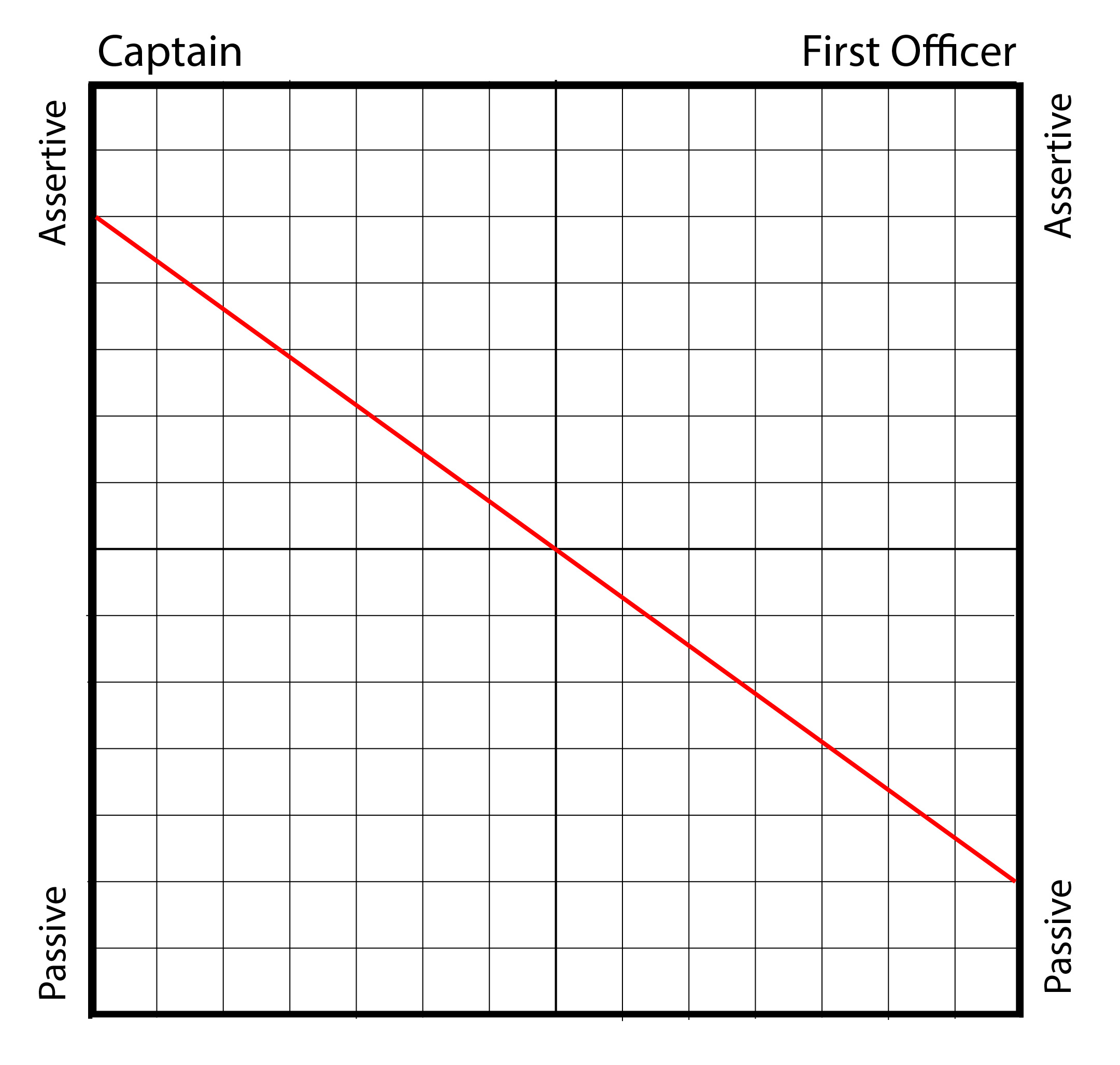

The gradient can be shaped by formal rank, seniority, cultural factors, or the organizational climate. In the context of an aircraft’s cockpit crew, it is usually framed in terms of the captain and everyone else on the crew. The gradient is often visualized at the captain’s assertive – passive range against that of the first officer’s. If the gradient is too steep, for example, the first officer may be discouraged from speaking up. An inverted gradient means the first officer is running the show. Many texts tell you the authority gradient should be flat. I disagree, for reasons I’ll explain shortly.

I think the best way to recognize how an authority gradient influences Crew Resource Management (CRM), is to examine a few dysfunctional authority gradient models with a case study or two, and then see how to improve on them.

1

Steep authority gradient

A steep authority gradient happens when the leader holds a dominant, often unquestioned position, and subordinates are reluctant to speak up or challenge decisions. Aviation seems especially susceptible where the captain is granted his or her authority by law, often greatly exceeds the rest of the crew’s seniority and experience and is recognized by the organization as the sole arbiter of disputes among the crew. By dint of experience alone, the captain may naturally be more assertive than the crew. The fact the pilot in charge is called the captain, may explain why the authority gradient tends to be steeper than flat.

Juan Trippe, the founder and CEO of the original Pan American World Airways, was said to have been the first to attach the title “captain” to the commanders of his ocean flying boats. The nautical parallel was intentional, the captain was seen as the “master of ocean flying boats.”

Those of us who fly may not appreciate the near dictatorship that can be found on ocean vessels. Sure, the U.S. Navy has adopted “Team Resource Management” as well as “Bridge Resource Management,” but the captain on a ship has considerable power. To get a feel for what it was like aboard the early Pan American World Airways first Boeing 707, don’t think about the modern Navy. Think along the lines of the HMS Bounty and Captain William Bligh and the mutiny of 1789. Now consider Captain Lou Cogliani, Master of Ocean Flying Boats. In his excellent book, “Skygods,” Robert Gandt introduces us to him through the experience of First Officer Jim Wood in 1971.

Jim Wood was the first of his class to complete first officer training. For his initial line trip he was scheduled to fly with one of the ancients, a senior captain named Lou Cogliani. The trip was to Honolulu and back.

Wood showed up an hour and a half early. His shoes were spit-shined. The three gold stripes on each sleeve glowed like neon. He was prepared to learn about flying from the old master.

"Sir," he said, extending his hand, "I'm Jim Wood, your first officer."

Captain Lou Cogliani, Master of Ocean Flying Boats, peered at the young man over the tops of his half-frames. It was the Look. He ignored Wood's hand. "How long you been flying, kid?"

"Ten years, including the Air Force and-"

"Never mind that shit. How long you been with Pan Am?"

"I'm new, sir. Just out of training."

Cogliani leaned over the operations counter. "Goddamnit, Evans," he barked at the clerk. "What's going on here? I told 'em I didn't want any new hires in my cockpit."

"I don't make the schedule, Lou. There's the phone. Call the chief pilot if you want."

Cogliani glowered at the phone. Then he shuffled through the paperwork for the flight to Honolulu. He ignored his new copilot.

They took off. Cogliani still had not spoken to Wood, except to order him to read the checklist.

Wood watched how the old master flew the 707. Captain Cogliani, he noticed, flew an airplane the way a bear handled a beach ball. He gripped the yoke with both hands. The veins stood out on his tensed forearms. He yanked, jerked, shoved, manhandled the protesting 707 all the way to 35,000 feet.

Wood glanced back at the flight engineer. The engineer nodded and rolled his eyes.

Wood was confused. Cogliani was a Skygod-a Master of Ocean Flying Boats. He was one of those legends that Wood most of all wanted to be like someday. He was supposed to be a hero. Something was wrong, thought Jim Wood. The Skygod was an asshole.

Approaching Honolulu, Cogliani commenced his descent from altitude too late, ignoring Wood's reminder about their rapidly diminishing distance from the airport. Too high for the approach, Cogliani had to fly a circle to lose altitude. Then he overshot the localizer, the final approach course. Honolulu Approach Control vectored them back onto an approach course straight into the runway.

At fifteen hundred feet above the field, the captain had still not called for the landing gear down. Wood kept his silence.

A thousand feet. Still no gear. Jim Wood bit his lip and said nothing.

At six hundred feet, Wood could stand no more. "Do you want the landing gear down, captain?"

Cogliani glowered at him. "Landing gear? Goddammit, I'll tell you when I want the gear down." Two and one-half seconds later, with a great deal of authority, he told him. "Gear down!"

No one, not even a new hire like Jim Wood, would dare suggest that the captain-a Master of Ocean Flying Boats-might actually have forgotten to lower his landing gear. Instead, Wood did something even more foolish. He laughed.

Three days later, in the chief pilot's office, Wood received his first lesson in Skygod protocol. The chief-the craggy-faced man who had welcomed Wood's class to Pan American-regarded the young man over the tops of his own half-frames.

"Do you want to keep your job, son?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then get this. You will sit there and raise and lower the captain's landing gear-on command-and keep your impertinent, newly hired mouth shut. Clear?"

"Yes, sir."

"Good. Get out of here."

Source: Gandt, pp. 85-87

Later that year, Cogliani crashed one of Pan Am’s cargo Boeing 707s short of the Guam International Airport, killing all four crewmembers on board. He flew the instrument approach one segment ahead of where the aircraft was and ahead of the verbal cues given to him by his first officer. But he wasn’t listening to his first officer, who for some reason failed to notice or correct the captain. The probable cause was “improper crew coordination which resulted in premature descent of the aircraft.” See the Case Study: Pan Am 6005.

That was in 1971. Surely we can do better than the Skygods from fifty years ago. Or maybe we have to relearn the lessons from previous generations.

Case Study: Air Blue 202 (2010)

The airplane crashed and killed everyone on board because of the captain's poor airmanship while flying the airplane into a mountain. But on the way to the scene of the accident he beat the first officer down to the point the right seat was occupied by a passenger, unwilling to speak up. See Case Study: Air Blue 202.

Case Study: Southwest Airlines 345 (2013)

The captain had a history of CRM problems and first officers tended to just put up with it, fooling the captain into thinking she was behaving normally. She wasn’t. While in the flare she took the airplane from the first officer and slammed the airplane into the runway, nose gear first. The aircraft was destroyed. See Case Study: Southwest 345.

I once went through initial training in a corporate jet paired with a recently retired airline captain. When he directed me to shut an engine down immediately after takeoff, I (very) politely suggested we wait until 1,500 feet. There were no indications of fire or severe damage. He said that he was the captain, it was his decision, and that I better shut the engine down immediately. The instructor froze the simulator and cautioned the captain to give his first officer more consideration, as that was better CRM. The captain became indignant, saying in his 25-plus years as a captain at his airline, his first officers said his CRM was the best. A few years later I met someone who knew him and said he was the typical “four stripe dictator” in the cockpit. I mention this because, as captains, we rarely get negative feedback. You need to look yourself carefully in the mirror each day to make sure a skygod isn’t looking back.

While the steep authority gradient results in an overbearing captain, at least there is a captain. It could be worse . . .

2

Inverted authority gradient

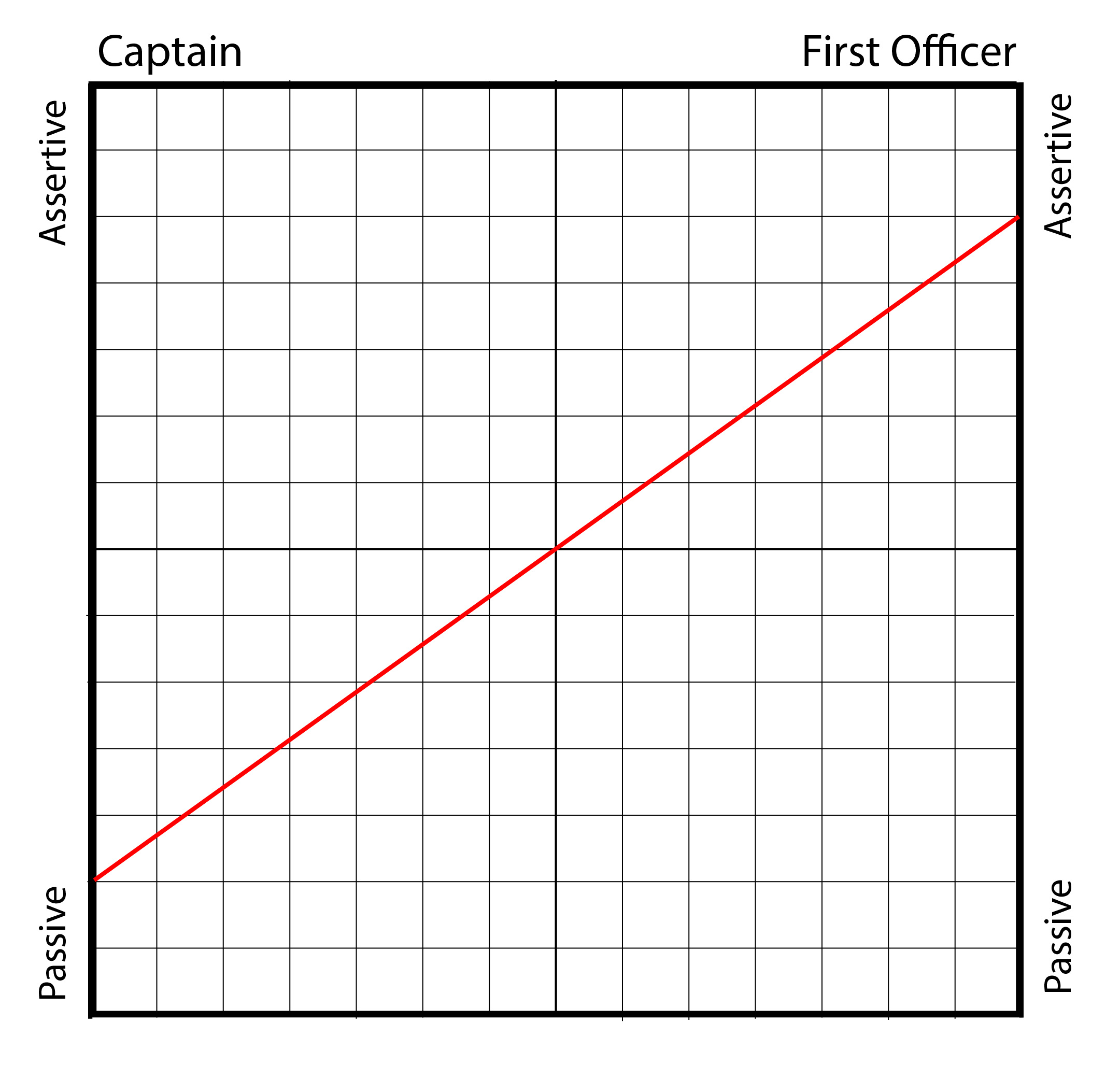

An inverted authority gradient happens when subordinates dominate decision-making or override the authority of the designated leader. This can happen when the formal leader lacks experience, confidence, or assertiveness, and more dominant team members take control. In aviation, this might happen when a newly qualified captain is paired with an older, more experienced first officer. If the captain is unable or unwilling to assert leadership, critical decisions may be made without clear authority or accountability.

I think an inverted authority gradient is comparatively rare in the airlines, given the seniority driven nature of the first officer to captain upgrade process. It is also not often seen in corporate aviation, since many of these pilots tend to swap seats and take turns as captains. But it does happen, even in the airlines.

Case Study: Northwest Airlines Flight 1482 (1990)

The captain had an extended leave of absence, and his airline was taken over by another company. After six years he was faced with a new airline and an airport he wasn’t familiar with. He was paired with a first officer on probation who took every opportunity to embellish his record and gain the captain’s confidence. The weather was poor and the captain willingly put his fate in the first officer’s hands. They never made it off the ground, destroyed their aircraft, and cost the lives of a crewmember and several passengers. See Case Study: Northwest 1482 & 299.

Two of my Air Force squadrons only hired pilots with previous instructor pilot experience and would start you over as a copilot, even if you were previously typed in the aircraft you were about to fly. It is a humbling experience that didn’t set well with many new hires. Pilots who chafed at this sometimes overcompensated by exaggerating their records and abilities. In some cases, they succeeded in inverting the authority gradient, but in so doing earned reputations as pilots to avoid. These pilots were eventually humbled, but only after embarrassing themselves. I later commanded a third squadron where half the pilots had previous instructor experience and had to start over as copilots. I encouraged these pilots to embrace their copilot status as an opportunity to learn anew, establish a good reputations as team players, and be assured that attitude was an important ingredient to upgrade and success.

3

Flat authority gradient

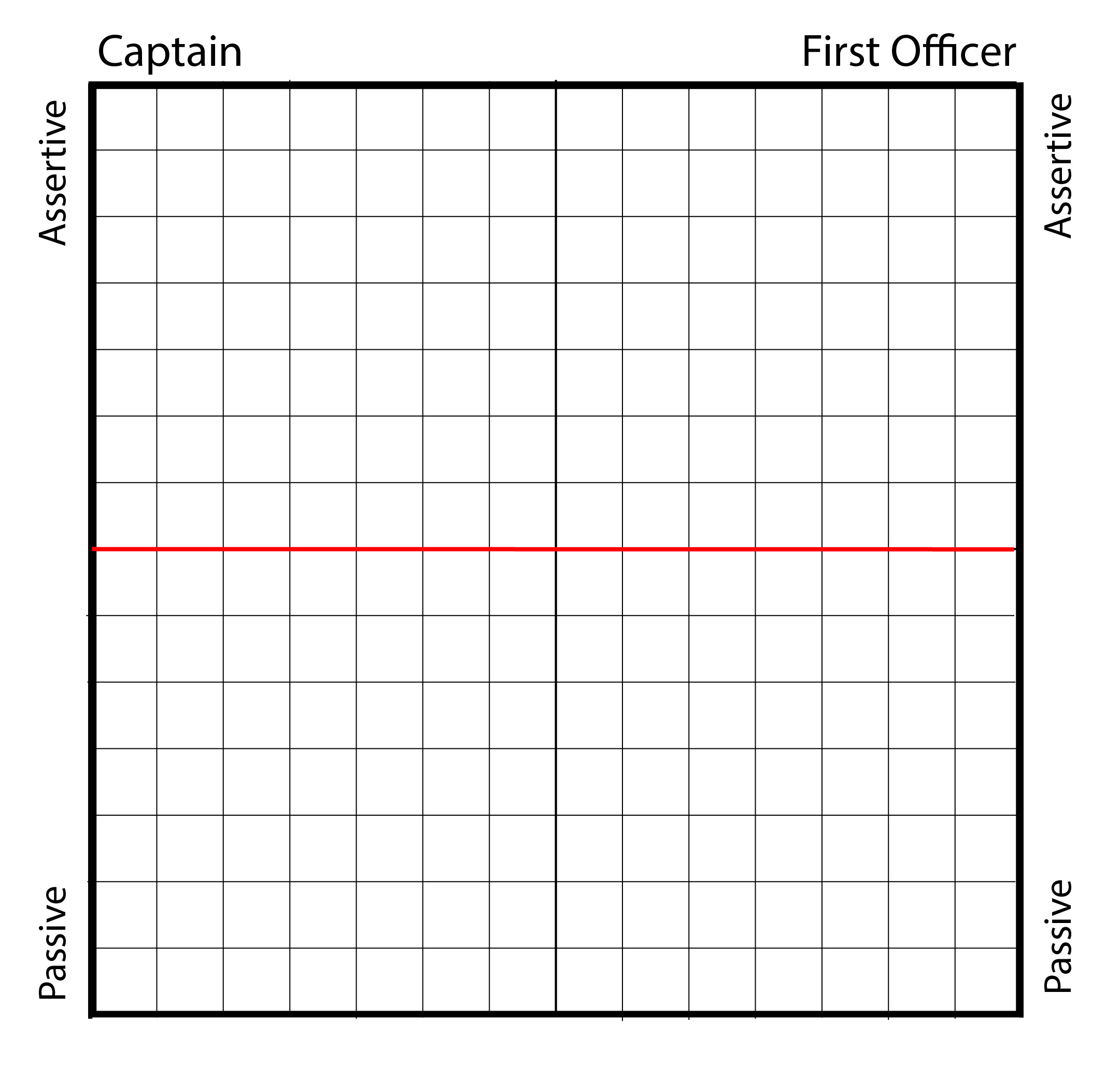

Many books on the subject say that a flat authority gradient is what you want. “A flat authority gradient denotes a more balanced distribution of authority, where all team members feel comfortable voicing concerns, sharing observations, and contributing to decisions. In a flat gradient, the leader remains ultimately responsible but fosters an inclusive, communicative team environment. Flat gradients are a core objective of modern CRM training. The philosophy encourages leaders—such as airline captains—to invite input, ask for feedback, and listen actively to their teams. This environment reduces the likelihood of human error going unchallenged and promotes better situational awareness.”

In terms of an aircrew, I disagree. A flat authority gradient implies equality, that the crew’s input is just as valuable as the captain’s, diminishing the fact that the ultimate responsibility sits on the captain’s shoulders. The captain should solicit input when time permits, and the crew should expect to be heard. But when time is critical, a captain’s decisions should be given great deference. A second issue occurs in the long term. A captain who regularly fosters an idea of equality on the flight deck cedes his or her command authority. After a while, the crew will come to expect an equal say and may even ignore a captain’s valid decisions.

Case Study: Gulfstream GIV N121JM (2014)

It was a flight department of two pilots: the boss and the subordinate. They took turns as the captain and the first officer; but flew together as equals. Perhaps they started down the path of Procedural Intentional Noncompliance by skipping a checklist. And then they started skipping procedures, such as flight control checks prior to takeoff. As equals, one was unwilling to challenge the other. I think the boss on paper didn’t feel responsible for their growing complacency, since he wasn’t alone on the slippery slope. On their last day as a crew, their last day living, they skipped a few more procedures and ended up off the paved surface of a runway doing more than 150 knots. See Case Study: Gulfstream GIV N121JM.

In one of my larger flight departments, we had two pilots who were cut from the same bolt of cloth. They both did whatever they could to avoid confrontation and would leave any decisions in the cockpit up for a vote. “Whatever you want to do is fine.” They did this as captains and first officers. Both had flown many times over the North Atlantic to Europe, but neither had experience in the South Atlantic to Africa. When I saw they were scheduled, I asked the boss to consider swapping one of them out, even volunteering to step in. The boss said I worried too much. The pair made it to Africa unscathed but ended up in a location without enough fuel to make their next stop. Each assumed the other had taken care of it. Equal responsibility equals no responsibility.

So, in my experience, a steep authority gradient is bad, an inverted gradient is worse, and a flat gradient might be somewhere in the middle. So what’s the right answer?

4

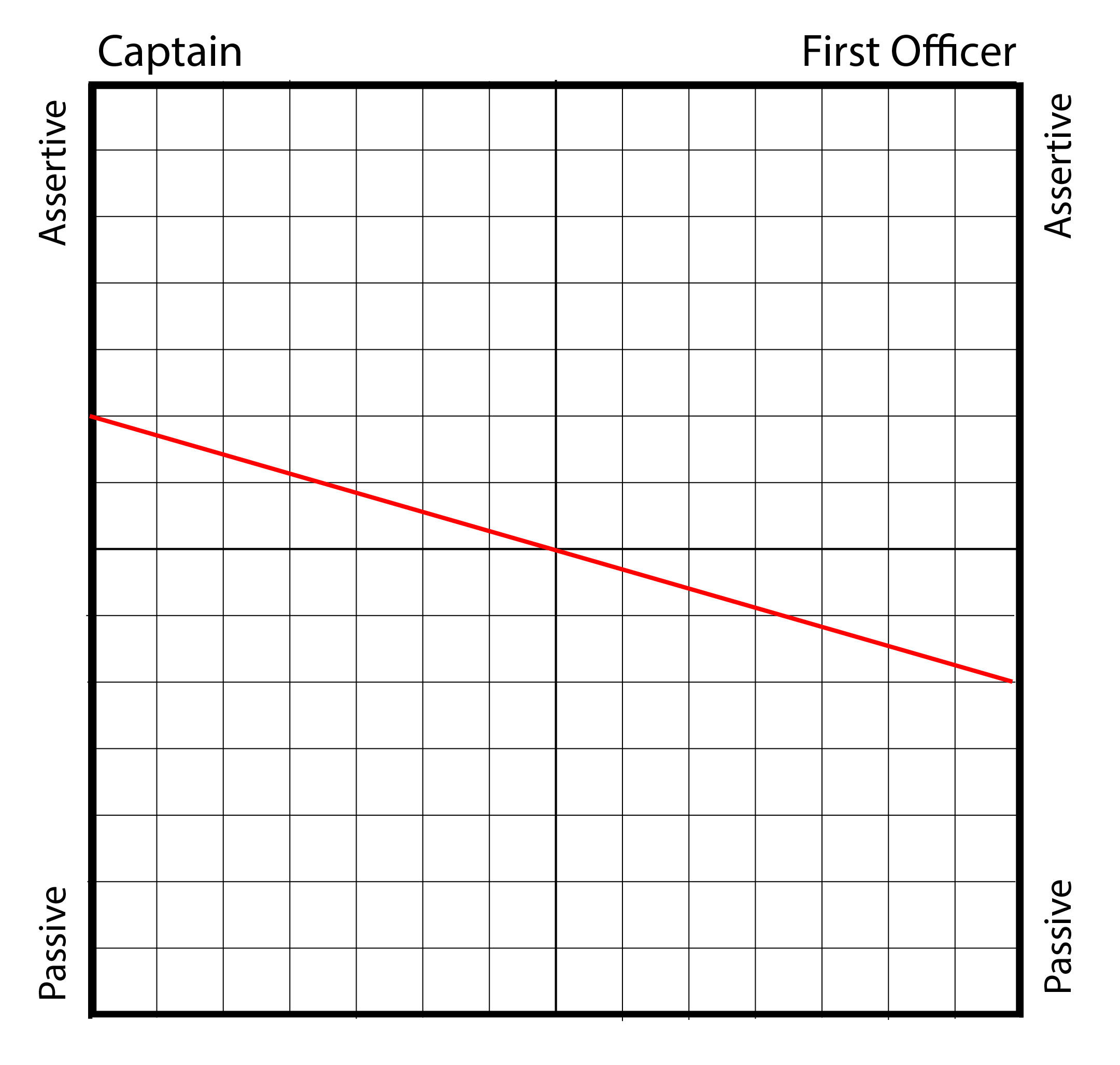

Optimal authority gradient

Proponents of the flat authority gradient say it allows team members to be more comfortable voicing concerns, sharing observations, and contributing to decisions. I say all that is good, so long as everyone understands the captain has the final say. It isn’t a democracy, especially when time is critical.

Case Study: United Airlines 1175 (2018)

As pilots we are at the mercy of many people, including those that designed, built, and inspected everything on the airplane. When something goes wrong, it might not adhere to how we've been trained. These three pilots were faced with a catastrophic engine failure over the Pacific that not only left them with one operating engine, but a failed engine that was flailing in the wind, causing extra drag and yaw that their training and manuals never anticipated. It took a decisive captain and a supportive crew, each operating at their best, to save everyone on board. They did everything right and provided a master class in Crew Resource Management and airmanship. See Case Study: United Airlines 1175.

When I first showed up to my Air Force Boeing 707 (EC-135J) squadron in Hawaii, there was a definite hierarchy in crews. The top crew, Crew One, was where all the standardization and evaluation crewmembers resided, and on top of that heap was Major Dan Gallo. I flew with him during my interview and there was no doubt, Dan was an exceptional pilot. The problem – there’s always a problem – is that Dan knew he was exceptional. He was quick to belittle others and the first time I used the phrase, “I was thinking . . .” he came back with, “I doubt that.” Everyone in the squadron, except his crew, hated him. I hated him. And then I was selected to be his copilot. He still treated me dismissively and I started to wonder about ways to escape the crew. The authority gradient remained very steep until I found out he was burning up the phone lines with Edwards Air Force Base, home of Air Force flight test, in an attempt to get the “Flight Envelope Diagram” for our airplane but was told he couldn’t have them. I sat down that night and drew up “V-G” diagrams (V for velocity, G for load factor) for our airplanes. The next morning, I showed him my work and earned his respect. For the next year he listened attentively to everything I said and whenever I was wrong, he politely corrected me. I learned more about flying heavy aircraft from Dan than ever before. When I upgraded and left his crew, I told him that if he treated everyone the way he treated me that last year, he would not only be an exceptional pilot, but a very popular pilot as well. “Popular? Do you think I care about being popular?” Apparently not. But the lesson was clear to me. As the boss, you are in charge, and you should never forget that. But that doesn’t mean you can’t listen to the crew and accept their counsel now and then.

Wherever your authority gradient is, adjust it so it is just a little clockwise of flat. It will make you a better leader (captain), make your followers (crew) appreciate you more, and it will make your organization (crew), that much better (safer).